For your reading pleasure, we gathered 21 recommendations from faculty in the College of Arts & Sciences for the best books and poetry to read in 2022. Enjoy!

Anindita Banerjee, associate professor, Department of Comparative Literature

My recommendation would be Yevgeny Zamyatin's novel “We.” Written in Russian in 1921, first published in English in New York City in 1924, and re-translated numerous times over the last four decades, this compact book about the world in the thirtieth century served as the inspiration for George Orwell's legendary “1984.” Though the connection between the two writers suggests that “We” is an all-too-familiar dystopia, the book is full of surprises for twenty-first century readers interested in crafting new, ethical ways of imagining and making the future. I would call “We” a preternaturally early experiment in "hopepunk" long before the term began to trend a few years ago.

Kaushik Basu, Carl Marks Professor of International Studies, Department of Economics and the SC Johnson College of Business

Reading the autobiography of someone you know well needs courage. I had to muster that up to read Amartya Sen’s “Home in the World: A Memoir” (Penguin Random House, 2021). It turned out to be one of the most engrossing books I have read. As the title of the book suggests, it is about making the world one’s home. Ranging over his early years in Dhaka, Mandalay, Kolkata and Cambridge, his battle with life-threatening cancer at the age of 18, and heart-rending descriptions of the Bengal famine of 1943, and with the broad message of universalism and humanism running through the pages, this is a book I can recommend to all.

Mabel Berezin, professor, Department of Sociology; director, Institute for European Studies

“Station Eleven” by Emily St. John Mandel is a quirky novel depicting what is left of life on earth after a fast-travelling deadly virus decimates the global population. Written before Covid-19, Mandel does a good job at exploring moral compromise as well as the hope for rejuvenation in a physical world from which civilization has departed. Chilling after Covid but also manages some unexpected plot twists!

Jonathan Boyarin, Mann Professor of Modern Jewish Studies, Department of Anthropology

Fred Peretz Cohn's “All the Small Things” (Broadstone Books) is a novel in verse. It's a gentle story about a young boy, his single mother, their neighbors and an inspiring teacher. Cohn is about my age and grew up in suburbs similar to those I knew, so the story rings true to my own childhood. Though the tone isn't sugar-coated, “All the Small Things” manages to reveal the sources of creativity in love.

Austin Bunn, associate professor, Department of Performing and Media Arts; director, Milstein Program

“Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee” by Casey Cep (Vintage, 2019) is a beautifully-wrought biography of a "true crime" novel that never came to be. This exploration of life (and death) in the Deep South is transporting, surprisingly moving, and a testament to the talent and empathy of one of our most beloved novelists who had to make peace with failure.

Andrew Campana, assistant professor, Department of Asian Studies

I recommend two poems by Nagae Yūki, “Paraffin Light” and “Moët & Chandon.” Nagae Yūki is one of Japan’s most exciting contemporary poets, whose work is just beginning to be translated into English. She draws her startlingly beautiful imagery both from classical Japanese literature and the language of geology, chemistry, and mathematics. In doing so, she captures what it feels like to be in a contemporary era filled with “connection” but still wracked with loneliness, in the world but apart from it, a feeling more prevalent during the pandemic era than ever before.

Carole Boyce Davies, Frank H.T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters, Department of Literatures in English, Africana Studies and Research Center

M. NourbeSe Phillip, “She Tries Her Tongue Her Silence Softly Breaks” (Wesleyan, 2015) is a classic series of poetic meditations on the question of language, of speech and silence as it relates to black women in particular. It explores her response to how language worked in the colonial context and how she is able to claim language for herself as a writer; i.e.: "What happens when you are excluded from the fulness and wholeness of language?" Its signature poem is "Discourse on the Logic of Language" which explores through science, biology and language the function of the tongue in articulation, between the "father tongue" -- the dominant colonial language and the "mother tongue" -- the language of closest intimate expression that is communicated through the mother.

Michael Fontaine, professor, Department of Classics

Two thousand years ago, the Roman statesman Cicero wrote one of the world’s first books on resilience, grit, and mental health. He was grieving the death of his daughter and nothing seemed certain anymore. Titled “Tusculan Disputations,” Cicero’s survival guide meditates on facing down death, coping with inner turmoil, and clarifying one’s highest priorities. “Tusculan Disputations by Cicero, translated by Quintus Curtius” (2021), an extraordinary new translation — the first in a century — brings Cicero’s forgotten classic back to life.

Durba Ghosh, professor, Department of History; director, Humanities Scholars Program

Everyone should run out and read “Catapult: stories” by Cornell's very own Emily Fridlund. The stories are chilling, astute, dark, and funny. Families in "uncozy homes," friendships that embody contradiction, affection that turns rancid. The prose is clear-eyed and daring in its exposition of what we might feel but are afraid to say. I laughed out loud and was unsettled at the same time.

Lawrence Glickman, Stephen and Evalyn Milman Professor in American Studies, Department of History

I really enjoyed and learned a lot from Alyson P. Brantley’s “Brewing a Boycott: How a Grassroots Coalition Fought Coors and Remade American Consumer Activism” (University of North Carolina Press). This book shows that intersectional activism has a longer history than we might think, as a coalition of labor, LBGTQ rights [activists] and Latinx worked for decades to get the Coors company and its owners, the Coors family, to change its labor practices and its conservative politics. Although the book is about only one company, Brantley examines so many facets of this topic that it can be read as an alternative history of the period from the 1960s through the 1990s.

Kim Haines-Eitzen, Paul and Berthe Hendrix Memorial Professor, Department of Near Eastern Studies

Fifty years of poetry from the brilliantly evocative, imaginative, and meditative Arthur Sze now collected in one volume, “The Glass Constellation: New and Collected Poems” (Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press, 2021) — what a treasure. These poems will put readers into “this moment that rides a wave stilling all waves,” the last line from one of his new poems in the volume, “October Dusk.” There are so many moments in these poems that arrest us with their potency and beauty. He’s a wonderful poet.

Caroline Levine, David and Kathleen Ryan Professor of Humanities, Department of Literatures in English

I really loved reading Helen Oyeyemi’s “Boy, Snow, Bird” (2014), a novel set in 1960s New England. It’s very much about racial segregation and gender, but it weaves these serious historical themes together with fairy tales and magic — from Snow White to Anansi the Spider to the Pied Piper of Hamelin. Every detail prompts thought and discussion.

Verity Platt, professor and chair, Department of Classics

I am thoroughly enjoying Jennifer Higgie’s “The Mirror and the Palette. Rebellion, Revolution, and Resilience: Five Hundred Years of Women’s Self-Portraits” (Pegasus Books, 2021). It is an accessible and engaging exploration of how women have asserted themselves as painters despite their historic exclusion from systems of training, patronage, and professional support networks. Often, a woman’s own body was the only “model” she could access. From Sofonisba Anguissola to Alice Neel, self-portraiture emerges not as an exercise in narcissism but as rigorous self-examination, experimentation, and creative expression.

Riché Richardson, professor, Africana Studies and Research Center

I recommend Honore’e Fanonne Jeffers’ beautiful award-winning volume “The Age of Phillis” for its epic engagement of the poet’s life and legacy, while incorporating so much sweeping historical perspective on Phillis Wheatley Peters, grounded in intensive archival research. It is also valuable for offering groundbreaking biographical insights on this author who launched the African American literary tradition in the late 18th century by publishing its earliest book, which also contributed crucial foundations for building American literature.

Aaron Sachs, professor, Department of History

Some of your assumptions about Herman Melville’s classic 1851 novel “Moby Dick” might be a bit off. Its language is ponderous and obscure? Well, the book’s most famous line is only three words long (“Call me Ishmael”). It’s apolitical? Well, Melville skewers slavery, colonialism, and Western Civilization in general. I think of the novel as a gay, comedic romp aboard a multicultural, inclusive whaleship. As Ishmael puts it: “Better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian.”

Adam Smith, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in Anthropology, Department of Anthropology

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow is a book that achieves through grand synthesis what many archaeologists have until now been doing through close empirical work. It reimagines early human history as populated by actual humans. Instead of dull automatons following the demands of historical evolution or imperatives of ecological systems, we find people arguing, making, negotiating, contesting, and experimenting, all with remarkable creativity and thought. The result is not only a book that revises how we think about humanity’s earliest eras, but also one that upends traditional intellectual histories of why we ever imagined the past differently. Most importantly, it opens new possibilities for reimagining the future.

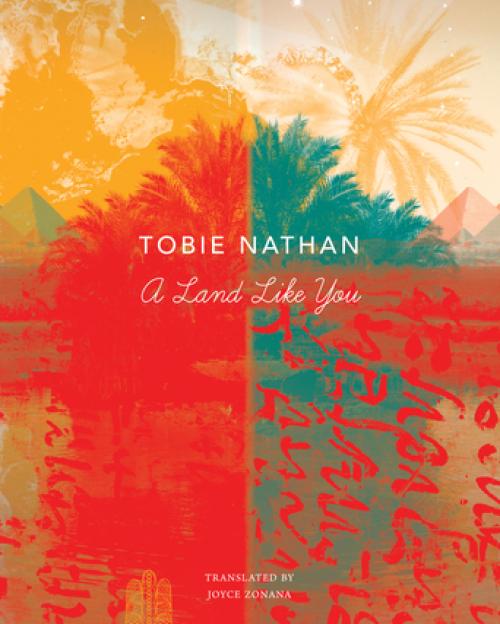

Deborah Starr, professor, Department of Near Eastern Studies; director, Jewish Studies Program

Tobie Nathan’s “A Land Like You” (Seagull Book, 2020) stimulates all of the senses in its portrayal of Jewish life in Cairo in the early 20th Century. This immersive novel weaves together narrative, folk traditions, and history. Joyce Zonana’s masterful translation from French captures the sensuous flow of Nathan’s prose.

Steven Strogatz, Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Applied Mathematics, Department of Mathematics; Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow

I’m looking forward to reading “The Weil Conjectures” by Karen Olsson. It’s a biography of two brilliant siblings, André, a mathematician, and Simone, a philosopher, mystic, and social activist. It also recalls, in a personal and intimate fashion, the years that the author herself spent studying math in college and her attempt to rekindle her passion for the subject now. “The Weil Conjectures” is a meditation on the creative life and on the odd digressions that lead to discovery.

Noah Tamarkin, assistant professor, Department of Anthropology

I would recommend a young adult novel called “Out of Darkness,” by Ashley Hope Pérez. Pérez is an academic as well as a novelist; she is a colleague from my former department Comparative Studies at the Ohio State University. The reason I think this is the book of the moment in spite of the fact that it has been out for several years is that it was recently targeted at a Texas school board meeting and has since been banned in some Texas schools. It's always a good time to talk about banned books, but this seems like an especially important issue to tackle at the moment.

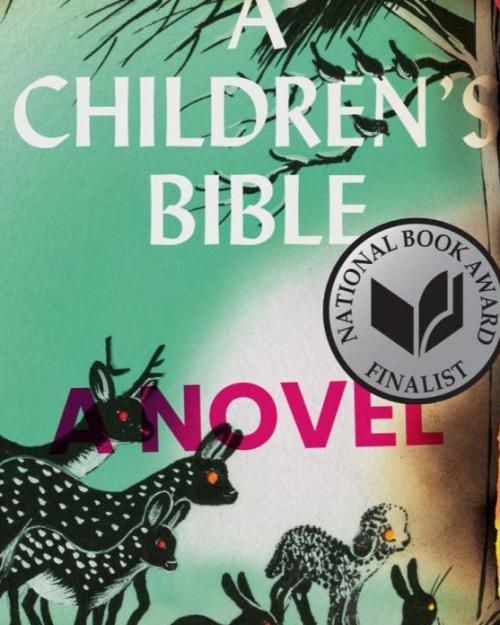

Stephen Vider, assistant professor, Department of History; director, Public History Initiative

A finalist for the National Book Award, Lydia Millet’s novel “A Children’s Bible” (2020) follows a group of children and teenagers whose parents have rented a country house just as a major storms rolls in. A kind of present-day “Lord of the Flies,” the book is gripping while reading and haunting afterwards, fully capturing the feeling of climate change as a slow-heating pot coming to boil and with it a generational sense of abandonment in the face of global disaster.

Cristobal Young, associate professor, Department of Sociology

“On Trails: An Exploration” by Robert Moor. This beautifully-written book starts out thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail (he finishes it!) and becomes an inspired meditation on: What is a trail? How are they made, and why do we follow them? Moor’s search for insight weaves a path through history, philosophy, science and nature writing. Making trails and using them to communicate is a fundamental kind of action, and seeing the connections Moor makes across many types of trails and paths is a delight.