It’s a quaint fantasy: pack up your belongings, hop on a plane and escape to a remote island or maybe even found a tiny nation of your own, where you can live unencumbered by the constraints of society.

What could go wrong?

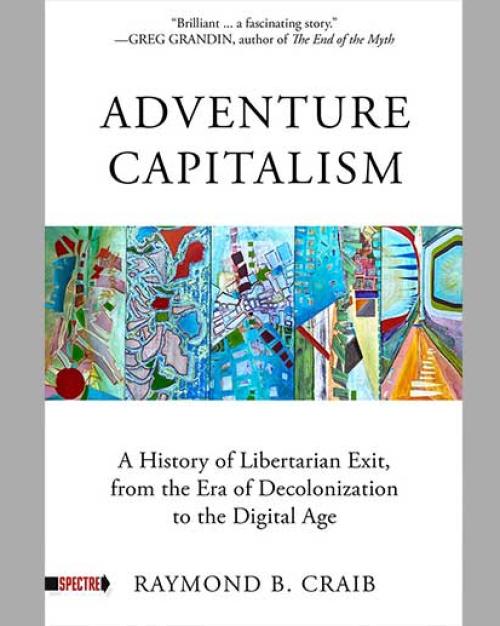

Plenty, according to Raymond Craib, the Marie Underhill Noll Professor of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. In his new book, “Adventure Capitalism: A History of Libertarian Exit, from the Era of Decolonization to the Digital Age,” to be published July 5 by PM Press, Craib explores the dubious track record of such utopian, free-market experiments.

From building private, sovereign platforms – or “seasteads” – on the ocean to establishing free private cities, which attempt to do the same on territory ceded to settlers by a government, “the promoters of these plans are all driven by a desire to not only escape taxes and regulation, but also to build a community where life is structured entirely through market transactions,” Craib said. These ploys often have calamitous consequences for local populations.

Craib spoke with the Chronicle about the book.

Q: Some people might be tempted to write off exit libertarians as comical or delusional crackpots. What are the consequences of the exiters’ actions?

A: These projects have serious consequences. I look at the case of exiters in the 1970s in places such as the Caribbean and the southwest Pacific, and their plans wrought havoc on communities attempting to emerge from the shadow of colonial rule. In the case of the New Hebrides, for example, exiters actually funded and armed a secessionist rebellion that they hoped, if successful, would facilitate the creation of a libertarian community and free trade zone. In other instances, just the mere prospect of exiter schemes created enormous political and social stress as communities worried about land loss and new forms of colonization.

Q: A reccurring figure in your book is Michael Oliver, who “founded” his own country, the short-lived 1972 Republic of Minerva. What makes Oliver such a great case study?

A: Oliver’s story is a compelling one: Jewish, from Kaunas, Lithuania, he was the only member of his immediate family to survive the Holocaust and was 17 or 18 when rescued by U.S. troops outside of the Dachau concentration camp. He then emigrated to the U.S. and made a home for himself in Nevada. His experiences made him understandably hyper-attentive to his political surroundings, and he worried about the threat of totalitarianism which, like many U.S. liberals and conservatives alike, he associated with communism as much as with fascism. (This resulted in a convergence between libertarianism and social conservativism that is central to how we should understand U.S. libertarianism.) By the 1960s, fearful of social change and inspired by the writings of hyper-capitalist advocates such as Ayn Rand and Friedrich von Hayek, Oliver self-published a small book (“A New Constitution for a New Country”) and began exploring places to build a new country. He was very strategic and focused his efforts on places trying to decolonize as well as reefs and seamounts such as the Minerva atoll in the southwest Pacific.

Q: Why were the 1960s and 1970s a particularly ripe time for exit projects?

A: These decades in the U.S. were shaped as much by the emergence of libertarian, anti-government politics as they were by the activism of the New Left. Libertarians organized against Roosevelt’s New Deal and the regulatory state at the same time that fears of ecological, demographic and monetary collapse grew. Just think of some of the famous writings of the era: Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s “The Population Bomb” (about overpopulation and famine), or Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” (about over-exploitation of resources), or even Ian Fleming’s “Goldfinger” (in which Auric Goldfinger plots to bring down the global economy by irradiating the gold supply).

At the same time, the wealthy sought to escape their social responsibilities – think of white flight to the suburbs as well as exit plans to oceans and islands. It was not a big leap to imagine a gated community on the high seas rather than in Orange County, or a capitalist commune on a remote island rather than in northern California.

Q: How do the original examples of libertarian exit compare with the like-minded efforts of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs today?

A: Recent exit strategists (the seasteaders, the free private cities advocates and the Start-Up Societies promoters) share much in common with the exiters of the 1960s. They, too, are free-market fundamentalists and want to create new countries, and have similar intellectual influences. But the differences are also worth noting. Perhaps the most striking is that they hew more closely than their predecessors did to the more Nietzschean aspects of Ayn Rand’s work. What I mean by this is that their projects are not driven by a fear of the masses and totalitarianism – indeed, they seem indifferent to the general public and express disdain for democratic politics – but by an urge, a will, to bend reality to their design. They seek not only to escape the state but then to recast it in their own image.

Q: Are there any examples of successful and responsible exit projects? What might that even look like? Or is their very premise part of the problem?

A: The premise is part of the issue. The hyper-capitalist orientation of the people I study sets them apart from other kinds of exit societies that one might find in the historical record: maroon communities forged by runaway slaves or by peoples fleeing state conscription and enslavement or autonomous territories, such as those founded by the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico. All of these might be considered experiments in territorial exit but they share little in common, ideologically and structurally, with those of Michael Oliver, of seasteaders and of the advocates of free private cities.

Form should not be privileged over content. Any analysis of exit needs to understand what it is people are striving to leave, but also what they are striving to build. Exile communities that grew from collective efforts to mitigate exploitation and that grew organically from the ground up are not comparable to escape plans that privilege property acquisition and individual sovereignty and tend to be preplanned and engineered from above. These bear distinct, and largely incommensurable, understandings of what constitutes freedom and of what constitutes oppression.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.