In 2013, Latin American studies scholar Irina R. Troconis went back to Venezuela after the death of Hugo Chávez to find herself trapped in the presence of the leader’s ghostly eyes.

“They were everywhere,” said Troconis, assistant professor of Romance studies in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S). “On buildings, on T-shirts, on billboards, on posters, on earrings, on keychains and on necklaces. And yet, the people I saw going about their day did not seem disturbed by them. In fact, they barely paid any attention to them.”

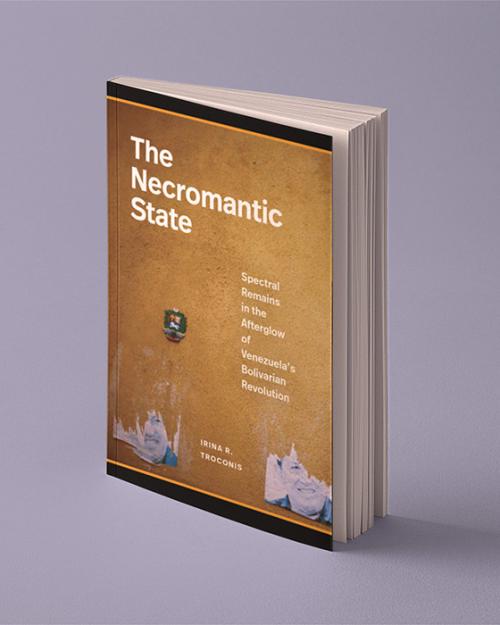

And it’s more than his eyes: in many forms, Chávez’s powerful presence has lingered in Venezuela’s public, private and digital spaces as a government-sponsored specter with true influence over the present, Troconis said. She examines this “perpetual state of haunting” in “The Necromantic State: Spectral Remains in the Afterglow of Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution,” published in March (Duke University Press).

Informed by a subsequent research trip in 2016, the book considers how ghosts can help a state secure its survival and ground its authority in moments of crisis, such as the one Venezuela is experiencing now.

The Chronicle spoke with Troconis about the book.

Question: What did you see and collect during your 2016 trip to Venezuela?

Answer: My trip in 2016 allowed me to gather the objects that in the book I call Chávez’s “spectral remains.” I spent three months between Mérida, my hometown, and Caracas, the country’s capital, taking photographs, talking to people and visiting places like Chávez’s tomb in the Cuartel de la Montaña and the National Pantheon, with the goal of gathering as much information as possible about the many shapes Chávez’s spectral afterlife was taking.

There were many highlights: the collectible phone cards showing Chávez’s growth from a toddler to the man who became president was one; the presence of his eyes on the building that served as the headquarters of the army in Mérida was another.

Q: How is “The Necromantic State” an experiment?

A: This book is an experiment, not a judgment. I say this to respond to a trend in studies about contemporary Venezuela that seem to perpetuate the political polarization that has defined the country in the last two decades by adopting an explicit political position that informs their contributions and frameworks. While there is a lot of value in that approach, I was more interested in thinking about a phenomenon – Chávez’s spectrality – that, in my view, collapses binaries such as people/state, pro-government/opposition.

The book is also an experiment in methodology. There is not a predetermined method to study ghosts, or a right or wrong discipline from which to write about haunting, particularly when the ghost or specter is not a metaphor or a figment of the imagination but rather a political and social figure, as I argue Chávez’s specter is. I thus propose “ghost h(a)unting” as an original method that encompasses my efforts to hunt down Chávez’s specter (to find and collect its material and visual manifestations) and to be simultaneously haunted by it. This method recognizes the value of studying what has been discarded, what gets repeatedly dismissed or taken for granted, and what is barely noticeable – things that do not neatly fit into any discipline – to understand how collective memory and political imagination take shape.

Q: This book focuses on Venezuela, but what other states today confront similar tensions between stately matters and ghostly matters, between past and present?

A: Every country is constantly grappling with its past and the ways it lingers in the present. What changes, perhaps, is the name we give to that grappling, and how it manifests visually and materially. That being said, we can think of Eva Perón, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Vladimir Lenin, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and Francisco Franco as examples of notable or iconic figures whose deaths, like Chávez’s, raised important questions regarding legacy, memory and futurity – questions that, I believe, have yet to be fully resolved, and that as such continue impacting the terms in which national belonging and political imagination are defined.

Q: What can break the spell that the ghosts you describe have over the country?

A: I conclude “The Necromantic State” with a call for discomfort that I articulate through my analysis of four performances by Venezuelan artist Deborah Castillo. Her work, I argue, brings the icon “back to the workshop” and, in doing so, renders the specter of male salvific heroes material and malleable in a way that provokes both attraction and disgust, and that allows for the development of a more reciprocal – and perhaps also disloyal – relationship with our glorious dead.

Ultimately, the book is not interested in advocating for the banishing or the vanishing of the specter. It insists instead on the need to grapple with it in ways that remind us that specters are not shadows, but the result of how we, collectively, think about history and how much we are willing to experiment with radically new ways of imagining the future. We create our own specters and ghosts. Forgetting that means forgetting that we are not just subjects but also agents of history.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.