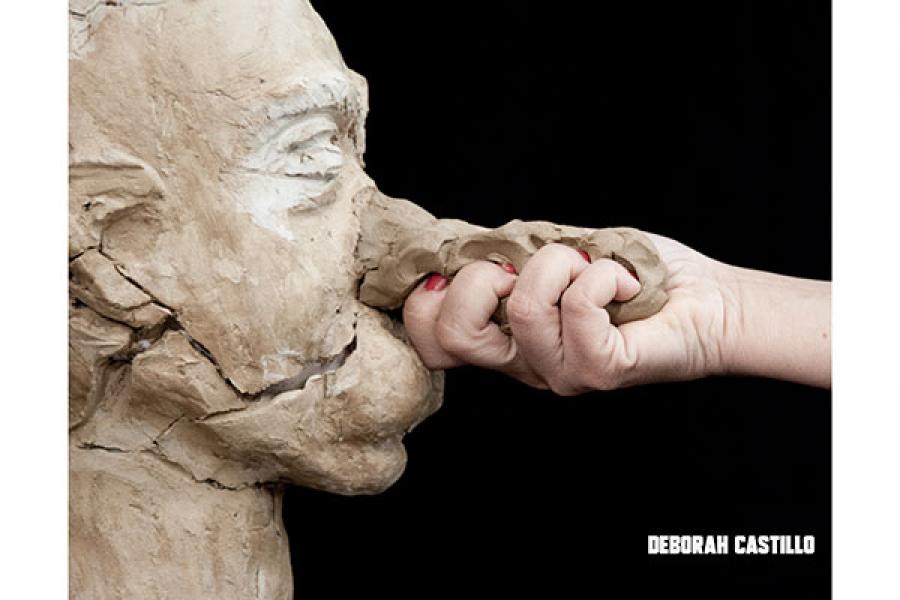

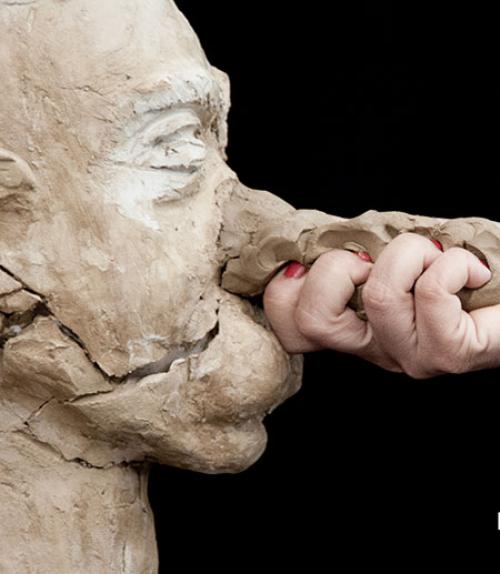

Deborah Castillo is an artist best known for what she has licked:

A soldier’s boot.

A bronze bust of Simón Bolívar, the revolutionary who led the secession of Venezuela from the Spanish Empire.

Through her colorful performance art, the Venezuela native provides jarring commentary about the ongoing political crisis in her home country and the failures of the Bolivarian Revolution.

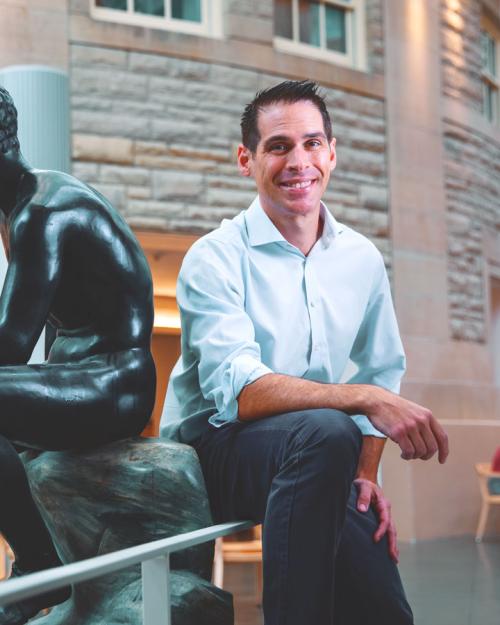

“Deborah Castillo: Radical Disobedience” is a new collection of critical texts on Castillo’s work, edited by Irina R. Troconis, assistant professor of Romance studies in the College of Arts and Sciences; and Alejandro Castro, a doctoral student at New York University.

Drawing from the fields of history, philosophy, cultural studies, political theory and performance theory, the volume’s six essays reflect upon the power of performance as an act of radical disobedience, within a unique digital format. The contributors analyze Castillo’s art against the backdrop of the Bolivarian Revolution – considering how her work speaks about power, the human body and the state, and lending nuance to Castillo’s boot-licking.

“This tongue has licked everything in strict silence: shoes, books, a heroic bust,” Troconis and Castro write. “Castillo’s tongue bites, bites where it hurts, where it is no longer possible to distinguish fruition from friction, and affliction from disgust or rage.”

This digital collection of essays “constitutes not only an effort to think about the work of the most important performance artist in Venezuela, but also to reflect on power, the body and resistance,” the editors write.

Castillo’s art incorporates performance, sculpture, photography and video; it has been exhibited in the United States, France, Mexico, England, Spain, Bolivia and Brazil. This volume analyzes her work between 2012 and 2018, beginning with an essay on “Lamezuela” (the performance that featured a photograph of Castillo licking a soldier’s boot) and culminating in an analysis of “Marx Palimpsest,” a performance that involved Castillo writing the Marxist manifesto on the wall and then painstakingly erasing choice passages while crafting new ones.

The six essays in the digital volume propose a series of perspectives from which to analyze Castillo’s body of work.

“Castillo’s work highlights how, in the face of a new project of radical collectivization, the singularity of a body – her own – appears as a response and a challenge to the violence of the signifier ‘people,’” the editors write. The essays also highlight how Castillo’s art challenges the legacy of Bolívar himself.

“The specter of Bolívar reappears in the Bolivarian Revolution as it has done so many times before: embodied, hypermasculinized, doctrinaire,” Troconis and Castro write. “Castillo’s feminine body makes explicit – by ironizing, deactivating, challenging, eroticizing, and reconfiguring – both his power and his sacredness.”

The editors hope that these essays not only provide scholarship on Castillo’s art, but also give voice to this unique body of work and its message.

“Castillo’s tongue is a powerful organ that dismantles the language of power by rematerializing what it licks, bites [and] hits,” they write. “Doing this in one of the most violent countries in Latin America is no small thing. Deborah Castillo gives a body to the state, remembering, forever, its fragility, and ridiculing the eloquence of its pompous performance.”

Joshua A. Krisch is a freelance writer for the College of Arts & Sciences.

Read this article in the Cornell Chronicle.