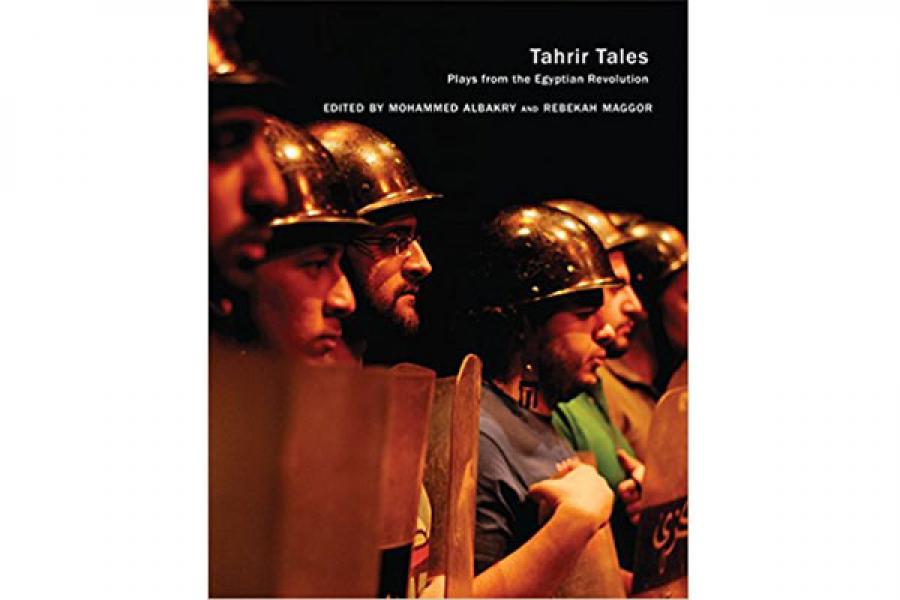

A reading and panel discussion of Rebekah Maggor’s anthology, "Tahrir Tales," will be held Monday, March 6, at 4:45 p.m. in the Film Forum, Schwartz Center.

Egypt’s Tahrir Square: ground zero for the Egyptian Arab Spring and the toppling of Hosni Mubarak’s government. During the dramatic mass protests, images of fierce clashes filled the news, but behind the mainstream media’s focus on violence, other things were developing inside the protests—among them a vibrant scene of performance and theatre.

“The occupation of Tahrir Square in Cairo unleased a surge of creative energy,” says Rebekah Maggor, assistant professor of performing and media arts. “Artists in Cairo and in cities across Egypt entertained the crowds with songs, poetry, sketches, and improvisation. Theatre and performance was instrumental in this quintessentially democratic moment. It was a way of mobilizing people, of having a conversation, and crystalizing goals. It was also a way for grassroots activists to challenge the official narratives propagated by the government controlled media.”

After Mubarak’s downfall, artists returned to their rehearsal halls to produce more structured and deliberate texts about their on-going experience of protest. Maggor has translated some of those texts in her new anthology, “Tahrir Tales: Plays from the Egyptian Revolution,” co-edited with linguist Mohammed Albakry. The book’s ten plays bring together work by both established and emerging playwrights, from the state theatres, independent theatres, and site-specific performance spaces. “While many of the plays arose directly from the writers’ experiences protesting in Tahrir Square, the collection actually spans from the twilight of Mubarak’s regime through the ascendancy of Egypt’s current president, Abdel Fattach el-Sisi.” Maggor says. “Collectively,” she adds, “these plays explore a full arc of popular uprising from genesis and progression to aftermath.”

As a theatre artist and scholar, Maggor’s focus is theatre of protest; in particular, she is interested in the work of emerging playwrights in the Middle East who are coming to grips with the aftermath of the “Arab Spring.” “I’m most interested in theatre that provides a lens onto the radically democratic political imagination of protest movements and offers unmediated and mostly uncensored perspectives of ordinary participants.”

Maggor is especially interested in the way that women’s voices are heard through these plays and the important roles they play beyond public protests. For example, in the gritty one-woman play They Say Dancing is a Sin the main character, a belly dancer, delivers a scathing monologue criticizing Egypt’s elite. “She is a modern-day Robin Hood who uses her wiles and artistic prowess to redistribute wealth from the plutocrats to the people.” Maggor says. Last spring, Maggor directed a workshop of the play at the Huntington Theatre in Boston.

“The audience learned a lot about women in Egypt from this play but they also found ways to relate the dancer’s story to issues facing women in the United States. For example, the play asks if it is ever possible for a woman to find liberation without financial independence. In other words, how does poverty effect a woman’s status?” says Maggor. “I deliberately choose to translate plays that provoke American audiences to think about the challenges we face in our own society. Sometimes, it’s easier for us to reflect on these difficult questions we’re not facing a mirror image, when there’s a geographical or other kind of distance.”

To provide historical and political context for the plays, Maggor wrote an in-depth introduction to the collection. “In my introduction, I tried to put these plays within the context of both the uprising in Egypt and also the broader artistic scene. These plays are only a thread in a rich tapestry of performance events and also part and parcel of a rich history of anti-colonial and anti-elitist protest theatre in Egypt.”

In addition to the time she’s spent in the Middle East, Maggor also earned an MFA in acting from the Moscow Art Theater School in Russia. “Having had the opportunity to live in different countries and take part in their theatre has really shaped my scholarship,” she says.

Her background as an actor has also shaped her approach as a translator and director, as has her expertise in voice and speech. “As a director, I’m interested in the way protest is revealed through performance, through the voice and body,” she explains. “As a dramatic translator, this visceral connection to the text has a huge influence on my creative process. I go to exceptional lengths to workshop my translations in performance with skilled actors. There are some things I can only discover in performance. ”

Current projects for Maggor include an anthology of contemporary Palestinian drama in translation, research on the creative process and politics of the Khashabi Ensemble Theatre in Haifa, as well as directing her translation of Desert of Light, a new play by Palestinian-Syrian writer Rama Haydar, for the PEN America World Voices Festival. Desert of Light premiered in the Cornell Department of Performing and Media Arts in September 2016.

A version of this article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.