By tweaking just one or two genes, Cornell researchers have altered the patterns on a butterfly’s wings. It’s not just a new art form, but a major clue to understanding how the butterflies have evolved, and perhaps to how color patterns – and other patterns and shapes – have evolved in other species.

The genes in question are especially interesting because they have been “co-opted” – they previously did some other job at a different place in the development process.

The experiment was made possible by the recently developed “CRISPR/Cas9” (Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) technology that can snip a single section out of a cell’s DNA. A CRISPR probe consists of a short strand of RNA – the cell’s “messenger” molecule – that will bind to a chosen DNA sequence to attract a “Cas9” enzyme that acts like a pair of scissors to cut the DNA at each end of the chosen sequence.

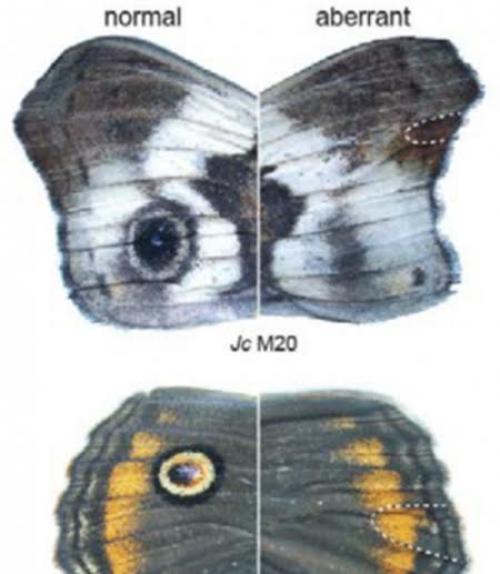

Injecting a CRISPR probe into a butterfly egg, researchers cut out a gene known as spalt, and hatched a butterfly lacking the large round markings known as eyespots. In another experiment, they removed a gene known as distal-less and produced more and larger eyespots. The experiments also produced changes in other parts of the wing design.

The distal-less gene in particular revealed itself as a jack-of-all-trades gene that plays roles in shaping several parts of the body. Deleting it not only caused the butterfly to have extra eyespots, but to have a shorter legs and antennae.

“People suspected these genes had something to do with wing patterns but nobody proved it,” said Robert Reed, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “It probably takes dozens or hundreds of genes to make an eyespot, so it was remarkable to find that only one or two genes are required to add or subtract these complex patterns. It is a beautiful demonstration of how animals are assembled as modules, much like a model kit.”

Reed and postdoctoral researcher Linlin Zhang report their results in the June 15 issue of the journal Nature Communications.

Butterfly wing patterns are of special interest to evolutionary biologists because they provide an easily accessible model of how natural selection chooses from many possible variations. “Variation is the raw material of evolution,” Reed said. The CRISPR/Cas9 technology offers great potential for understanding how this variation originates, he added.

Butterfly wing designs can be a defense against predators. Some butterflies are poisonous to birds (or maybe just taste bad) and birds can learn to recognize the designs that say “I’m not good to eat.” Other butterflies have evolved to mimic the dangerous species. The large round markings on some butterfly and moth wings have come to be called “eyespots” because the spread out wings of the insect may look to a predator like the face of something big and dangerous. The designs also influence mate selection.

The researchers worked with the butterflies Vanessa cardui, known as the “Painted Lady” or “Cosmopolitan” and Junonia coenia, the “Buckeye." Their work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

This article originally appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.