Both academic studies and popular representations of LGBTQ history have typically focused on battles for public space and visibility. As gay liberation activists put it in the 1970s: “Out of the closets, into the street.”

But the intimacy of domestic space was an equally crucial aspect of LGBTQ life in the postwar era, according to Stephen Vider, assistant professor of history and director of the Public History Initiative in the College of Arts and Sciences. Vider delves into that history in his new book, “The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II,” published Dec. 24 by the University of Chicago Press.

Vider spoke with the Chronicle about the book.

Question: Why has the history of LGBTQ people and domesticity in the U.S. been so overlooked and understudied?

Answer: The attention that historians have given to events like the Stonewall Riots has reinforced traditional ideas about how social and political change happens – that “real” history only happens en masse and in public. LGBTQ home spaces, by contrast, have tended to look privatized and apolitical, and so have been largely overlooked in LGBTQ histories. At the same time, mainstream histories of home and family have almost always ignored LGBTQ people, or treated them as the exception to the heterosexual norm. My book places home life at the center of LGBTQ history, and LGBTQ history at the center of the history of home. It’s a retelling of 20th century LGBTQ history from the inside out.

Q: Your book makes the case that the domestic space is not just a site of living; it is a place of performance as well. How so?

A: It’s a mistake to call the home simply private. I think of the home in modern American culture as a portal to the public. People are constantly negotiating how they make their home lives visible, who gets to come in, and what they’re allowed to see. In that sense, domestic life is not a rigid set of rules but a kind of theatrical script that is always being reinterpreted. There’s a story I discuss in the book from the 1960s: a lesbian couple lived next door to a gay male couple and came up with a scheme to purchase identical dressers. That way, whenever anyone’s parents came to stay, they could quickly switch a few drawers from one apartment to the other and pretend they were just two straight couples. LGBTQ people understood intuitively that home was a kind of stage, where people perform their identities for each other and even themselves.

Q: What makes the postwar era such an important time for connecting queerness with the American home?

A: Right after World War II, what is often described as the “traditional” American family – the male breadwinner with his dutiful wife staying home to raise the kids – was promoted in vastly new powerful ways. The 1950s were also a period of heightened stigma against queer and trans people. Many activists at that point wanted to figure out how queer people could fit into this domestic vision of American society. Only a decade later though, a new generation of queer activists would start using domestic space to challenge those same ideals. They were calling for the traditional family and home to be abolished, and they were deeply invested in creating new models.

Q: You note in the book’s introduction that home “has been a crucial though contradictory space in LGBTQ life and politics.” Why is it contradictory?

A: Home can be both a site of alienation and a place of self-expression and connection. The final chapter of the book looks at caregiving programs that emerged in response to HIV/AIDS, called buddy programs. Volunteers were paired with someone living with HIV/AIDS to provide everyday forms of support. That could be helping to cook and clean, shopping for groceries, or simply spending time with someone. This was a time when there was so much unexamined fear and stigma against people living with HIV/AIDS, and people could become incredibly isolated in their homes. What the volunteers understood was that home was also a space where ordinary acts of caregiving could make a profound difference – and actually help people to come together across their differences.

Q: To explore this history, you examined a “domestic archive” that included organizational records, images, diaries and letters. What inspired this approach and what were some of the most remarkable objects you found?

A: Searching for the domestic archive means looking differently at materials within formal collections that other historians might have skipped past – for instance, a printout of an early internet bulletin board, where users were exchanging stories about living with and caring for people with AIDS.

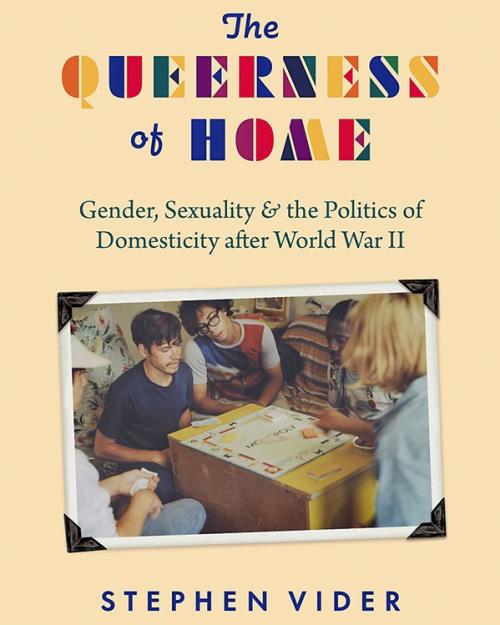

My favorite image in the book is a photograph by filmmaker Bruce Pavlow of a group of queer young people from 1977, playing a board game at Survival House, one of earliest group homes for homeless LGBTQ people. I had spent a lot of time looking at financial records and grant applications that the directors of the house put together and thinking about how they were trying to explain their work to the city and state government. But seeing Pavlow’s photograph helped me to feel closer to their experience and to think about how they shared space with each other and its meaning for them. I was very honored when Pavlow allowed me to borrow the photo for the cover of the book.