Herpetologist Harry Greene had challenged himself this year to finish the manuscript of his next book, “Monkey, Snakes and Spears: Reflections on Wildness.” In between writing, he planned to spend some weekends in Mason County, Texas, getting his new property – Rancho Cascabel (“Rattlesnake Ranch”) – ready for habitation. He had lived in this Texas Hill Country as a child, where he first began searching for snakes among the yucca, prickly pear cactus and rugged limestone and granite boulders.

Greene and his partner, Kelly Zamudio, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, were at the ranch in mid-March when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. In the interest of safety, they decided to stay on in the 10-by-20-foot, barely habitable cabin that had once been a hunting shack. They spent long days emptying the place of garbage and scrubbing grease off the walls. They piped in water for the outside sink, built an outdoor shower and installed an incinerator outhouse.

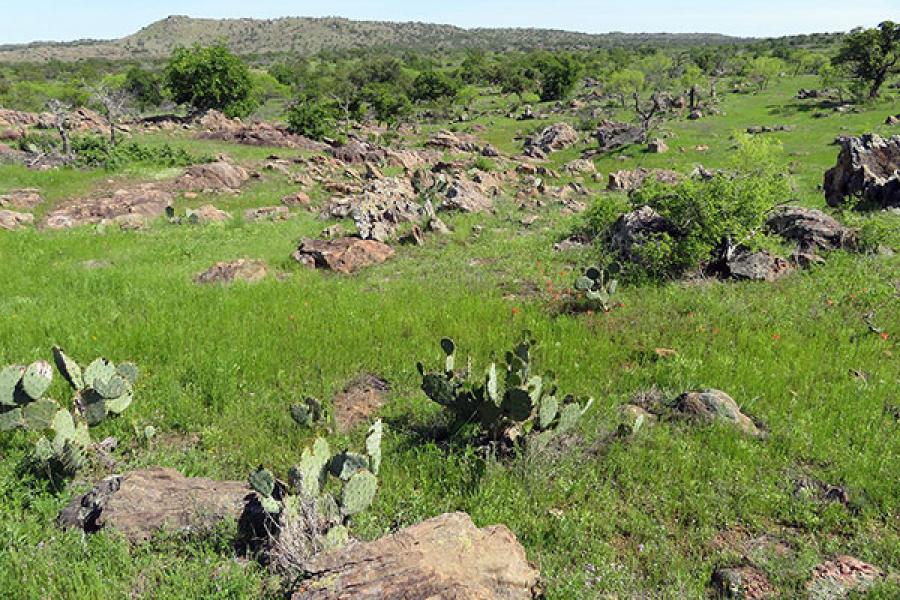

But what they really cared about was making the land itself habitable. They are committed to restoring – “rewilding” – the 183-acre ranch, with its thorny mesquites and towering pecan trees, likely planted by earlier inhabitants, rising above the rolling plains. Massive gneiss boulders lie scattered amidst the prairie grass, brown now in summer’s heat but lush with wildflowers in spring.

Greene says the goals of rewilding are slightly different from “preservationism,” the reigning paradigm in U.S. environmentalism, which “idealizes the wild as a place where humans leave only footprints and only take photos,” says Greene, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology. “I’ve come to think that this is literally unrealistic: Humans have always been part of nature, and so preservationism amounts to a peculiarly Eurocentric, colonial-centric vision.”

In contrast, rewilding means restoring an area to its maximally diverse state of biological richness, by reintroducing animal species, or close approximations, that had been previously native to the area.

Rewilding requires “pondering relationships with other species,” Greene says, “and how they can involve informal, messy contracts regarding what we’ll tolerate and what level of real or perceived cost we’re willing to pay in order to coexist.”

Greene says Rancho Cascabel’s rewilding follows an ethical aesthetic framework, one that stresses being a reciprocating participant. “You take from nature, you give to nature and you do it respectfully,” he says, “because if you take from nature, you have an obligation to give back to it.”

The final chapter of “Monkey, Snakes and Spears” will be about rewilding the Earth, Greene says, with a more personal ending than he’d originally planned: It will describe his efforts to help Rancho Cascabel return to a more authentic, healthy state.

The ranch has been farmed at least since the late 1800s – as evidenced by an overgrown family graveyard – and had been badly overgrazed. That is why Rancho Cascabel will have only a small herd of Texas longhorn cattle.

Greene explains that although longhorns are not New World animals, they are descended from feral cattle that have adapted to the local southwestern landscape over hundreds of years. “They survived the worst drought in Texas history by eating cactus,” says Greene. “They can be a sort of proxy for missing organisms like bison, and even more distantly missing species like extinct shrub oxen. There’s a lot of evidence that at least the moderate presence of a big herbivore is a good and typical, authentic component of a temperate grassland.”

Like big grazing herbivores, prairie dogs, which actually are highly social ground squirrels, are another important component of a healthy southwestern ecosystem that is currently missing from Rancho Cascabel. Greene hopes to install a prairie dog town on a portion of the property, providing prey for foxes, hawks, owls and other predators. It’s not an easy endeavor. To prepare, Greene will till and mow; install starter burrows and soft-release cages, as well as circles of diesel-soaked flagging to confuse nearby predators; prepare many dozens of pounds of sweet potatoes for cage provisioning; construct cardboard sun shades for the release cages; and monitor the town daily.

Greene has been chronicling the ranch’s current ecosystem on social media. His posts so far include the ornate tree lizard, desert cottontail, striped bark scorpion, western coachwhip snake, coyote – and his least favorite, the orb-weaver arachnid that has set up housekeeping in his outdoor shower.

Thanks to an anonymous donor, Greene and Zamudio have been able to install eight trail cameras around Rancho Cascabel. In addition to helping identify resident species – both native and invasive, like a feral cat – the cameras provide the occasional snapshot of social behavior, such as two gray foxes interacting.

Eventually, Greene and Zamudio hope to build a slightly larger, more comfortable house on their property, so they can use the cabin for educational activities, like field teaching for local high school students.

Their rewilding goals for Rancho Cascabel will be more feasible because the property is contiguous with three other bigger properties, all owned by friends – including former A.D. White Professor David Hillis, a University of Texas biologist – who share their hopes of restoring and responsibly stewarding the land.

Not all of Greene and Zamudio’s work on Rancho Cascabel involves the ecosystem. They’re also hoping to restore the 19th-century cemetery with the help of his sister-in-law, an archaeologist.

Someday, Greene says, he would like an eco-friendly “green” burial in that cemetery, in the Texas Hill Country where his heart has been since he was a boy, looking for snakes in the rocky scrubland.