Queer writers often find that conventional narrative forms – the marriage plot, for instance – don’t work to tell their stories.

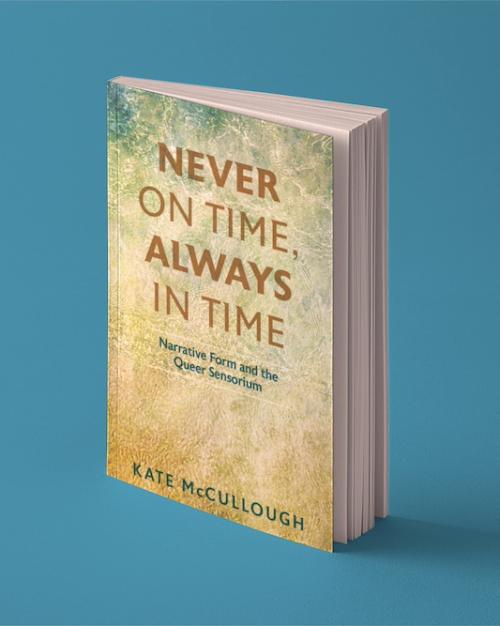

To compensate, “they rework representational forms to make space for the telling of their tales,” according to scholar Kate McCullough.

One way to rework narrative form is time, said McCullough, associate professor with a joint appointment in feminist, gender and sexuality studies, and literatures in English in the College of Arts and Sciences – such as the way Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir, “Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic,” layers text and image to create a protagonist who is a version of her younger self.

In “Never On Time, But Always in Time: Queer Temporalities and Narrative Form,” McCullough examines four recent books, including bestselling novel, “The Book of Salt,” and “Fun Home,” which inspired a Tony-winning musical, to explore how queer narratives focus on the body and its senses to find alternative ways of experiencing and presenting time.

A&S spoke with McCullough about the book.

Question: It’s tempting to say that time passes at the same rate for everyone. Why does the conventional conception of time fail the queer experience?

Answer: Time has long been a means of disciplining people and societies, particularly since the Industrial Revolution and its reliance on clock time. Queer scholars read heteronormative time, or what we might call Reproductive Family Time, as one of these disciplining forces. It’s easy to see how this envisioning of time – as a chronological “normal” path from birth to school to marriage to children to retirement to death – serves to manage the temporal patterns of bodies and sexualities of whole populations, producing a certain kind of (heterosexual) subject.

Q: How do bodily sensations through the five senses allow queer narratives to expand, play with or break with time in the books you examine?

A: My book demonstrates how authors represent non-normative temporalities produced by experiencing the senses and valorizing them “queerly.” Especially since the Enlightenment, sight has been the privileged sense in the Western word, so in queer narratives we often find challenges to the primacy of sight.

For example, in Monique Truong’s “The Book of Salt,” a novel whose protagonist is a queer chef, the temporality of food and foodways is experienced through taste, smell and touch. These senses enable a distinctive narrative strategy that I call “reiterated ephemerality.” Reiterated ephemerality refers to a temporal pattern of food and commensality in which the repetition of a fleeting culinary moment – the production or consumption of a meal, for instance – consequently accumulates into a sense of duration that swerves away from heteronormative time.

Q: What does the future look like for “queers and other people who do not feel the privilege of majoritarian belonging, normative tastes, and ‘rational’ expectations,” as José Esteban Muñoz puts it in your book’s epigraph?

A: This is a big question. From my vantage point, a survivable future calls for justice for all people, an equitable division of resources and power, and an emphasis on connection and compassion. Literature helps to produce this by allowing us to inhabit other people’s worlds, their beliefs, their values, their ways of seeing the world. This is a first step to understanding and connecting with others.

Is there thriving ahead? Well, this is not an optimistic moment for queers and many others, but I am reminding of the saying that “hope is a practice.” I’m continuing to practice, day by day.

Q: “Fun Home” has reached a wide audience through the musical, and “The Book of Salt” is a recent bestseller. What might these and similar books communicate to the larger world, including readers outside the queer community?

A: In a moment when the incoming national administration has explicitly made a rollback of LGBT rights part of its platform, these texts can, at the very broadest level, at the very least remind people – or introduce them to the fact – that all humans have rights. This very simple fact seems to have been forgotten by many. On a more sophisticated level, these texts might demonstrate the enormous creative and resilient power that lives in LGBT people.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.