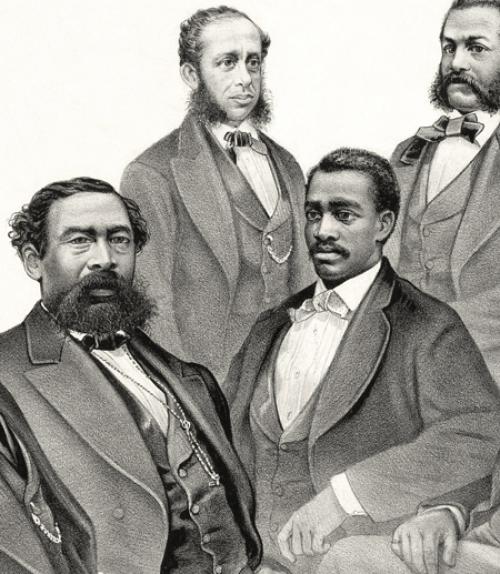

It’s a little-known fact of U.S. history that in the early 1800s, while most African-Americans were enslaved, freed black men in some states had the right to vote.

As the country grimly inched closer to the Civil War, states began to take that right away. These restrictions came with an expansion of voting rights for others, as requirements that a voter must own property were removed for white men.

Similar patterns of simultaneous expansion and restriction of political rights emerged in 19th-century France and the United Kingdom, too.

For the first time, this pattern is explained, in a new book by David Bateman, associate professor of government. “Disenfranchising Democracy: Constructing the Electorate in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France,” describes the first cross-national account of the relationship between democratization and the restriction of voting rights.

“If you want to understand democratization and how it actually occurs in practice, you need to think about who is being excluded,” said Bateman, an expert in American political development.

In all three countries, the coalitions pushing for democratization expanded the body of voters in numerical terms but also redefined who was excluded. Each coalition had a vision of what “the people” should look like so as to accomplish their particular political agenda over the long term.

“They were redefining who is ‘the people’ and what is the purpose of the country,” Bateman said. “They were asking, what should we be aiming at? What do we need to preserve, and what do we want to accomplish?”

In the U.S., freed black voters were seen as undermining the national compact with slavery, Bateman said. “Black free voters were expected to vote for antislavery candidates and the very fact of being black and having citizenship rights would undermine the association between color and slavery,” he said. “The democratizers felt excluding African-Americans, even if they were free, was essential for national unity and for accommodating the prejudices of racist whites.”

In the United Kingdom, the democratizing coalition extended voting rights to the middle and professional classes even as they took away the rights of Irish Catholic farmers and many of the English working class who could vote. “The Whigs who pushed the democratizing reforms thought that the working-class voters were much more likely to vote for conservatives – Tories,” Bateman said.

France saw a renewed and intensified commitment to the exclusion of women at the ballot box. In most countries, liberals supported women’s right to vote, but in France it was the far-right Catholics who supported suffrage and the left-leaning Republicans who opposed it, Bateman said. “Republicans in France were terrified that women – who were more religious, closer to the Roman Catholic Church – would want to bring back the king,” he said.

Each of these moments of simultaneous democratizing and disenfranchisement was a complex process of “people-making,” Bateman said.

“You don’t just have an existing people and include more of them in the electorate; you don’t enfranchise and disenfranchise along a sliding scale of inclusion,” he said. “Rather you’re redefining boundaries and the purpose of the electorate.”

The book is one of the first in the literature on democratization to look at the process of exclusion. Other authors have analyzed either the movement away from authoritarianism or the process of expanding the right to vote. “What I saw was, the same process doesn’t unfold the same way everywhere, but similar dynamics occur across different countries,” he said.

The book’s findings suggest those who envision new democratization projects must think about not only expanding the number of people with access to voting rights but also the purpose of the political project. The idea is to connect institutional rights, such as the right to vote or the right to live in a nongerrymandered district, to a broader political purpose of political community. “That is, what type of people should we be?” Bateman said.

The book is also relevant in terms of voter suppression, Bateman said. “I want us to ask how current disenfranchisement projects are trying to reconceive of what political community looks like in the United States,” he said, “or who ‘the people’ are in America.”

This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.