Long considered exclusively male, it turns out that sperm become partly female after mating, according to a new study of fruit flies.

The paper, published March 7 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, revealed that by four days after a sperm enters a female, close to 20% of its proteins are female-derived.

The researchers discovered that first seminal fluid proteins and then female proteins bind to sperm inside the female.

Some of the female proteins that attach to sperm are metabolic enzymes, which led the researchers to hypothesize they may be supporting the sperm’s viability, though more study is needed.

“In flies, and in many other organisms, sperm live for many days [inside the female], so the female may be providing enzymes they need to keep them nourished and healthy,” said Mariana Wolfner ’74, professor of molecular biology and genetics and a Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow in the College of Arts and Sciences, and a senior author of the paper, “The Life History of Drosophila Sperm Involves Molecular Continuity Between Male and Female Reproductive Tracts.”

Sperm have been known to live for at least 10 days, spanning an entire generation, within female fruit flies.

In a collaboration with co-senior authors Scott Pitnick, professor of biology, and Steve Dorus, associate professor of biology, both at the Center for Reproductive Evolution at Syracuse University, members from each research lab dissected sperm from thousands of mated female flies. The researchers all used the same strain of flies and reproduced the experiments exactly the same way across the labs.

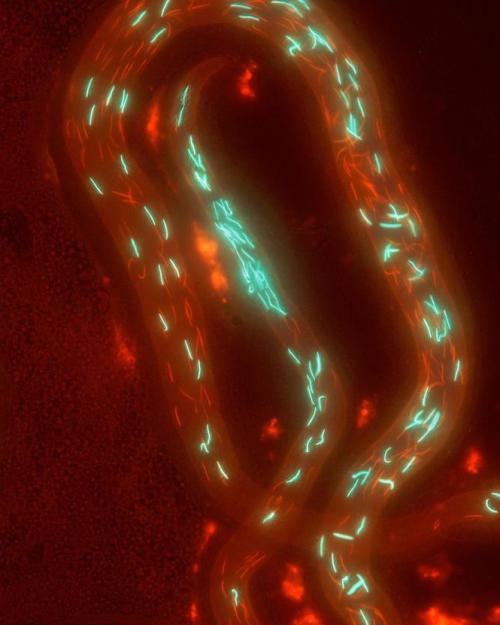

Sperm were removed from the female during various stages post-mating; 30 minutes after mating, when the sperm mix with seminal fluid proteins and female reproductive tract-derived proteins in an organ called the bursa; two hours after mating and again four days after mating, when sperm are stored in specialized organs within the female.

Each sperm sample was then washed in a buffer solution that removed any proteins that were not tightly bound to the sperm. The researchers then identified the proteins associated with the sperm using mass spectrometry, a technique in which proteins are broken down into small fragments that are then precisely measured for weight and charge. These measurements allow researchers to reconstruct which proteins were in the sample.

They identified close to 2,000 proteins in the sperm over the four days of samples, with about 1,000 of them innate to the sperm. Soon after mating, 122 seminal fluid proteins were found to attach to the sperm. The researchers suspected that the remaining sperm-associated proteins came from the female. Members of the Dorus and Pitnick labs labelled females with heavy isotopes, so they could specifically identify female-derived proteins bound to the sperm. By day four, most of the seminal fluid proteins had disappeared, but the researchers identified 328 female-derived proteins bound to the sperm, which made up nearly one-fifth of the total sperm proteins.

Thus, this study showed that although sperm come from the male and are composed of male DNA and cellular structures, once inside the female they are no longer completely male.

“If the female proteins act to stabilize sperm, you can imagine situations where reproduction could fail if a female failed to produce one of those important proteins,” Wolfner said.

Also, evolutionary biologists have been known to paint reproduction as male sperm working against a hostile environment within the female reproductive tract, but if sperm adopt female elements, that evolutionary argument becomes far more nuanced and likely includes aspects of molecular continuity and cooperation, Wolfner said.

Co-authors include Erin McCullough, a postdoctoral researcher, and Emma Whittington, a former doctoral student, both at Syracuse University, and Akanksha Singh, a former postdoctoral researcher in Wolfner’s lab.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.