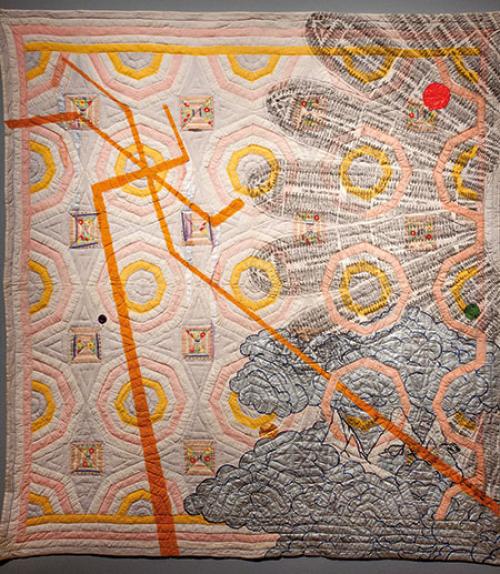

Image: Quilt by Sanford Biggers from the Cartographer’s Conundrum, MASS MoCA, 2012, 77 x 70 inches

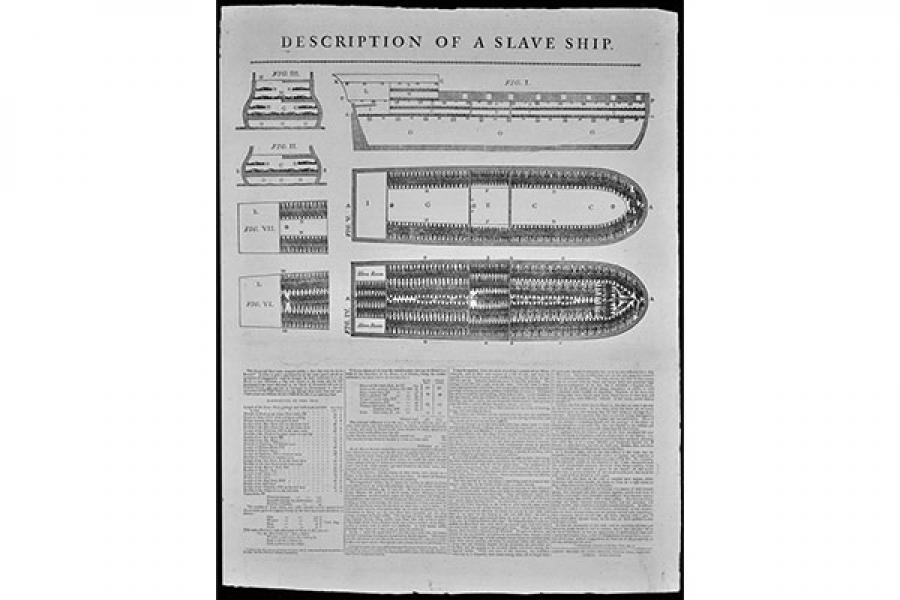

In the fight to end slavery, the 1788 image of a slave ship had an outsized impact on legislators and the public. In her new book, “Committed to Memory: the Art of the Slave Ship Icon,” art historian Cheryl Finley provides the first in-depth look at the influence of the 18th-century slave ship schematic and how it became an enduring symbol of black resistance, identity and remembrance.

Created by British abolitionists based on evidence collected from ships, the original wood engraving depicts the human cargo hold of a slave ship, with annotations describing how much space was allotted to each person; how they were separated by sex; and how male captives were shackled “to discourage insurrection” during the four- to eight-week voyage. The schematic was originally intended to influence legislators regulating slave ships and eventually helped to end the trans-Atlantic slave trade, then the institution of slavery itself. The image was easily reproduced; by the end of the 18th century, as many as 200,000 had been circulated, printed on handbills and broadsides, in newspapers and in books.

“It was the first image to expose people to the barbarism of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, showing its high level of violence in the way it visualized human suffering,” said Finley, associate professor of history of art in the College of Arts and Sciences. “There’s an appeal at the end of the description for everyone who reads it and sees it to support the abolition of the slave trade.”

London Committee, Description of a Slave Ship, 1789, wood engraving, 24 × 19 inches

Over the last 230 years the icon has become “a medium through which diasporic Africans have reasserted their common identity and memorialized their ancestors,” Finley writes. In “Committed to Memory,” Finley discusses “mnemonic aesthetics,” a process of ritualized remembering that undergirds contemporary art about slavery. Since the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, the image has been a touchstone for African-American poets, writers and artists, according to Finley, who have transformed the image into poetry, literature, visual art, sculpture, performance and film. Many visual artists use the image to make points about contemporary issues, such as on posters protesting the prison industrial complex and the rise of global capitalism.

“For me, what’s key is the icon’s longevity and its enduring presence in the minds of black artists and their allies, who’ve used the image to show offenses against human rights and violence against black people and black bodies,” Finley said.

It took Finley nearly two decades to complete her book: Each time she thought her research was finished, she’d discover another artwork that showed something new about the icon. In her book, Finley examines why the image has such continuing resonance and why, she writes, there is “an urgent need for ordinary people to attempt to embody it, to revisit the terror it represents, [and] to re-enact its profound silence and pain.”

One reason Finley offers is that, like crucifixion imagery, the slave ship icon embodies death and life and has been compared to both coffin and womb. Writes Finley: “It is a site of death, of dying Africans, and of new life, of a people who would persevere in the face of slavery and unspeakable cruelty to become a free people who helped define the modern era.”

On Sept. 13 in New York City, Finley will speak about her book at the Institute of African American Affairs at New York University. Admission is free, and the public is invited.

In the spring, Finley will teach an undergraduate course at Cornell, Slavery and Visual Culture, based on her research. The class will look at historical works as well as contemporary art, and will include a trip to New York City to see related exhibits and galleries.

Second Book Release

In a second work published this year, “My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South,” Finley and co-authors explore the art-historical significance of contemporary Black artists working throughout the southeastern United States. The catalog book accompanies the exhibition “History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, through September 23.

Written by Finley, Randall R. Griffey, Amelia Peck, and Darryl Pinckney, “My Soul Has Grown Deep” discusses the paintings, drawings, mixed-media compositions, sculptures, and textiles in the exhibit, from the assemblages of Thornton Dial to the renowned quilts of Gee’s Bend. The authors illuminate shared artistic practices, including the novel use of found or salvaged materials and the artists’ interest in improvisational approaches across media. According to the authors, the diverse works tell the compelling stories of artists who overcame enormous obstacles to create distinctive and culturally resonant works of art.