Both Megan Barrington and Christian Tate have a favorite rock.

Barrington’s is shaped like a bird’s head; while Tate’s takes the form of a shoebox created from lava.

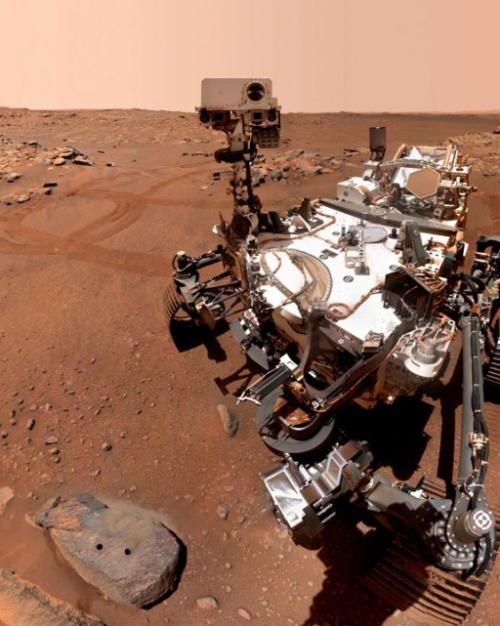

Those rocks are 196 million miles away, on Mars, and the Cornell doctoral students encountered them as part of the search for signs of ancient life via the NASA Mars 2020 mission’s Perseverance rover, which landed on the red planet Feb. 18, 2021.

Barrington, who studies Earth and atmospheric sciences, and Tate, in astronomy, have been breathing, thinking, living and working on the red planet Mars, digitally commuting from our own blue world.

“This is my first mission,” Tate said. “I feel so lucky to be on such an influential mission as a graduate student.”

The students work in the laboratory of Alex Hayes ’03, M.Eng. ’03, associate professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences. Hayes is a co-investigator on Mastcam-Z – the Perseverance rover’s main camera. He conducted research as a Cornell undergraduate and graduate student on the Spirit and Opportunity rover missions on Mars.

Through Cornell, the students also are members of the Mastcam-Z team, under the leadership of the instrument’s principal investigator Jim Bell, professor of astronomy at Arizona State University and an adjunct Cornell professor. While at Cornell, Bell served as the PI for the panoramic camera, or PanCam, on Spirit and Opportunity.

The rover’s newest generation Mastcam-Z uses two focusable, zoomable cameras placed on the rover’s mast. They see the colors red, green and blue, plus the infrared part of the spectrum. From a hundred yards away, they can focus on a small stone.

Tate – an image processor on the team – presents Martian rocks like you’ve never seen them before: In three-dimensional images that require no cardboard 3D glasses.

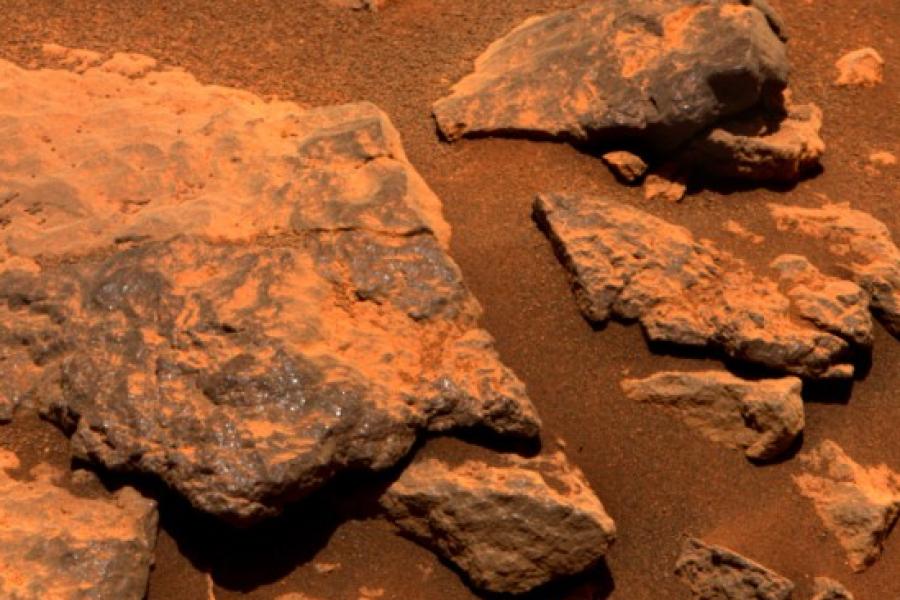

“I’m very proud of this one. It’s called Rochette,” he said. Rochette means “little rock” in French and the images were captured by Mastcam-Z on Aug. 21.

“It is an unusual rock,’ he said, and it seems like you are walking around it. “We weren’t expecting to encounter volcanic or igneous rock on the bottom of an ancient lake.”

After the raw rover images arrive from Mars, Tate adjusts the image color and loads images from several angles. He runs the pictures through software that stitches and reconstructs the 3D scene. “Sometimes the software doesn’t always get it right,” he said. “There is a lot of tweaking, which can take around 10 hours. That’s what takes time.”

In its Earth year on the red planet, Perseverance has driven about 700 feet from its original landing spot at Jezero Crater, ferried the first helicopter Ingenuity through the solar system and sent more than 200,000 photos back to Earth.

On another part of the team, Barrington – a U.S. Army veteran who served in Afghanistan as an expert marksman – serves as an uplink lead for the Mastcam-Z team. She cooperates with other instrument groups to plan the daily camera maneuvers to capture Jezero crater’s best targets.

“Team members on strategic planning shifts work together to decide the mission goals for the next several days,” Barrington said. “It’s a basic plan for which instruments get used and using that information we start on what operations will look like, and we refine it and adjust to make sure the plan gets carried out.”

In the course of her work, one bedrock shape caught her eye – it looked like the head of an eagle. Sometimes, science team members get to name rock formation or special Martian locales. Since Barrington had served in the Army’s famed 101st Airborne Division – the air-assault group nicknamed the “Screaming Eagles” – she named the site “Tsídii,” a word for bird” in the Navajo language.

Soon, Barrington will transition to a new position on the Mastcam-Z team to evaluate chemical compositions, which will match her two-part doctoral thesis on the geomorphology of Mars and the geomorphologic evolution of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

“With the comet, I’m looking at how smooth sediments and regions – with fine grain particles – and regolith (unconsolidated rocky material) evolve over time,” she said.

In the meantime, the rover Perseverance works every day. NASA and the European Space Agency are collaborating on the Mars Sample Return Campaign – a proposed program to collect samples Perseverance examined and cached, and bring them back to Earth – possibly including Tate’s Rochette.

While the students live on Mars, their families remain down to Earth. In the first year of the rover mission, Christian Tate and his wife, Nicole, had a baby boy, Charlie, and Megan Barrington, and her husband, Matthew, also had a baby boy, Henry.

Said Christian Tate: “That’s the human element.”

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.