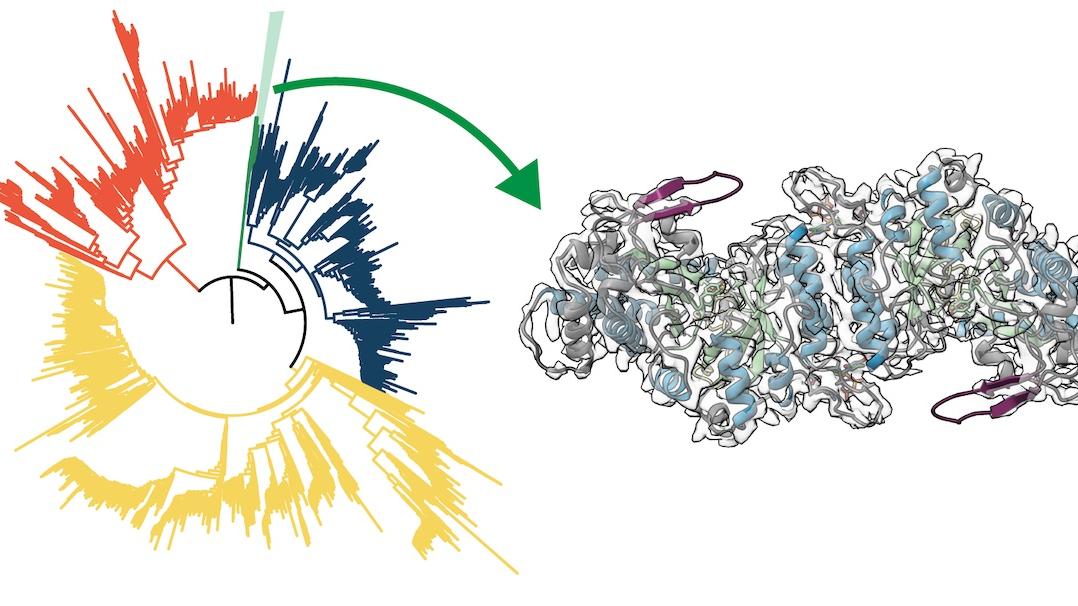

Cornell scientists have created an evolutionary model that connects organisms living in today’s oxygen-rich atmosphere back billions of years – to a time when Earth’s atmosphere had little oxygen – by analyzing ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs), a family of proteins used by all free-living organisms and many viruses to repair and replicate DNA.

“By understanding the evolution of these proteins, we can understand how nature adapts to environmental changes at the molecular level. In turn, we also learn about our planet’s past,” said Nozomi Ando, associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology in the College of Arts and Sciences and corresponding author of the study. “Comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the ribonucleotide reductase family reveals an ancestral clade” published in eLife Digest Oct. 4.

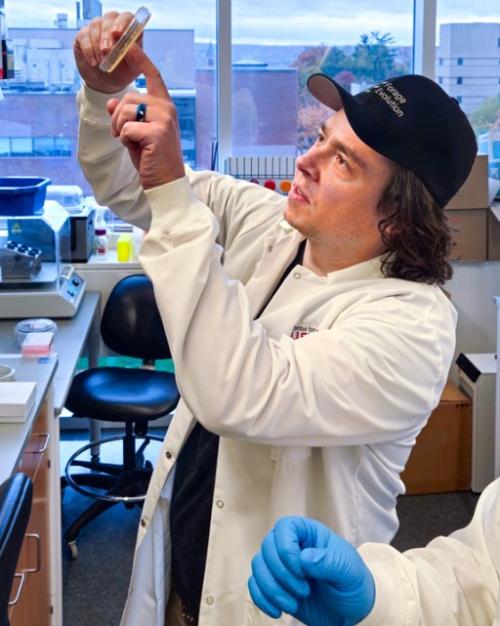

Co-first authors of the study are Audrey Burnim and Da Xu, doctoral students in chemistry and chemical biology, and Matthew Spence, Research School of Chemistry, Australian National University, Canberra. Colin J. Jackson, professor of chemistry, Australian National University, Canberra, is a corresponding author.

This undertaking involved a large dataset of 6,779 RNR sequences; the phylogeny took several high-performance computers a combined seven months (1.4 million CPU hours) to calculate. Made possible by computing advances, the approach opens up a new way to study other diverse protein families that have evolutionary or medical significance.

RNRs have adapted to changes in the environment over billions of years to conserve their catalytic mechanism because of their essential role for all DNA-based life, Ando said. Her lab studies protein allostery – how proteins are able to change activity in response to the environment. The evolutionary information in a phylogeny gives us a way to study the relationship between the primary sequence of a protein and its three-dimensional structure, dynamics and function.

RNRs are thought to have ancient origins because they catalyze the reaction of converting RNA building blocks into DNA building blocks, Ando said, making them ideal for finding a molecular record.

“This chemistry would have been needed to transition from the hypothesized RNA world to the DNA/protein world that we currently live in,” Ando said. “Based on the co-factors that RNRs use, it also is clear that this enzyme family has adapted to oxygen increasing in the Earth’s atmosphere. Both of these transitions took place billions of years ago.”

When scientists build a phylogeny of a protein family, they calculate how the currently existing sequences came to be, Ando said. In that process, they have to estimate what happened in the past to get the sequences that exist now.

The researchers calculated the RNR phylogeny by gathering a dataset of more than 100,000 sequences and curating down to a computationally tractable dataset of 6,779 sequences while maintaining the diversity of the entire family, Burnim said. The sequences range in length from about 400 to 1,100 amino acids. Using models of how amino acids mutate, they compared the sequences with each other to determine when they diverged.

From this work, the researchers discovered a new distinct group of RNRs that would explain how two different adaptations to oxygen on Earth emerged within this protein family.

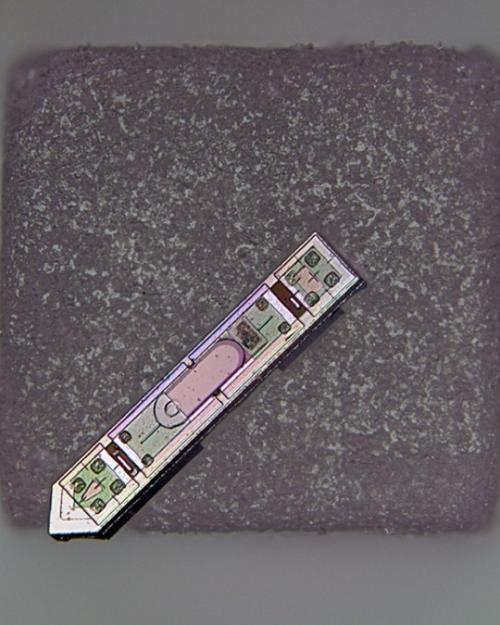

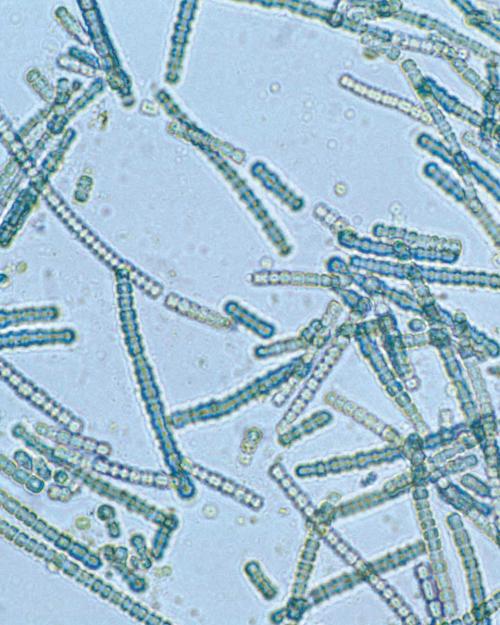

They used small-angle X-ray scattering at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, cryogenic-electron microscopy at the Cornell Center for Materials Research and the artificial intelligence program AlphaFold2 to study the RNR from Synechococcus phage S-CBP4, a virus that infects a cyanobacterium, Xu said.

“When we calculated the RNR family tree, it turned out that there was a branch of RNRs that we didn’t know was a distinct lineage,” Ando said. “This branch included sequences from marine organisms including cyanophages. Our characterization of one of the sequences suggests that there was an early adaptation to oxygen. The cyanophage connection was interesting because it suggests that their hosts (cyanobacteria) were around at the same time, and cyanobacteria are credited for oxygenating the Earth.”

The findings support the idea that molecular adaptations to oxygen occurred much earlier than the large-scale environmental changes to the planet, as dated by geochemical records, Ando said.

This first-ever unified evolutionary model for all classes of RNRs could offer many future directions for the field, Xu said.

Ando plans to use the same approach to study how enzymes with the same overall structure evolved to catalyze totally different chemical reactions.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institutes of Health and by New York state’s Empire State Development Corporation.