German studies professor Patrizia McBride was drawn to montage because of its storytelling power.

“It assembles objects and narratives by culling fragments from different areas and then reassembling them,” she said in a “Chats in the Stacks” talk Feb. 15 at Olin Library, discussing her latest book, “The Chatter of the Visible.”

The book, an exploration of montage and modernist aesthetics in 1920s and ’30s Germany, was selected for the “Knowledge Unlatched” series, a crowdsourced funding model that makes books available online for free.

In the early 20th century, montage was associated with an all-out assault on representation and any kind of ordering principle, including narrative, McBride said.

“It was seen as registering the collapse of social order in the after-war period, at a moment of trauma and disillusion in Germany, something completely antithetical to the thrust of narrative and storytelling,” she said.

But montage’s mixing together of codes and media offers a new understanding of narrative that emphasizes the materiality of the medium, the moment of perception along with sense-making and interpretation, she argues in her book. “It valorizes the ways in which the forms of the world are mediated through new technologies like photography that interact with human senses and influence our ability to register reality,” she said.

Montage, therefore, responded to a crisis of narrative in Weimar Germany. “This perceived challenge was tied to a print culture, and to ways of understanding the relationship between text and image,” McBride explained.

The rise of graphic arts, particularly in commercial art, created a new field that bypassed the traditional literary modes of print culture. The principle of montage was to take something and insert it in a new context – to make it strange. It treated storytelling as a kind of treasure trove of discovery, she said.

This unorthodox mode of storytelling had a great deal of overlap in advertising, McBride said.

“German ads were much more radical in their abstractions and their almost aggressive way of activating the audience,” she said – and she was fascinated by how fragments were taken out of their usual context and made to function in new ways in advertising montages.

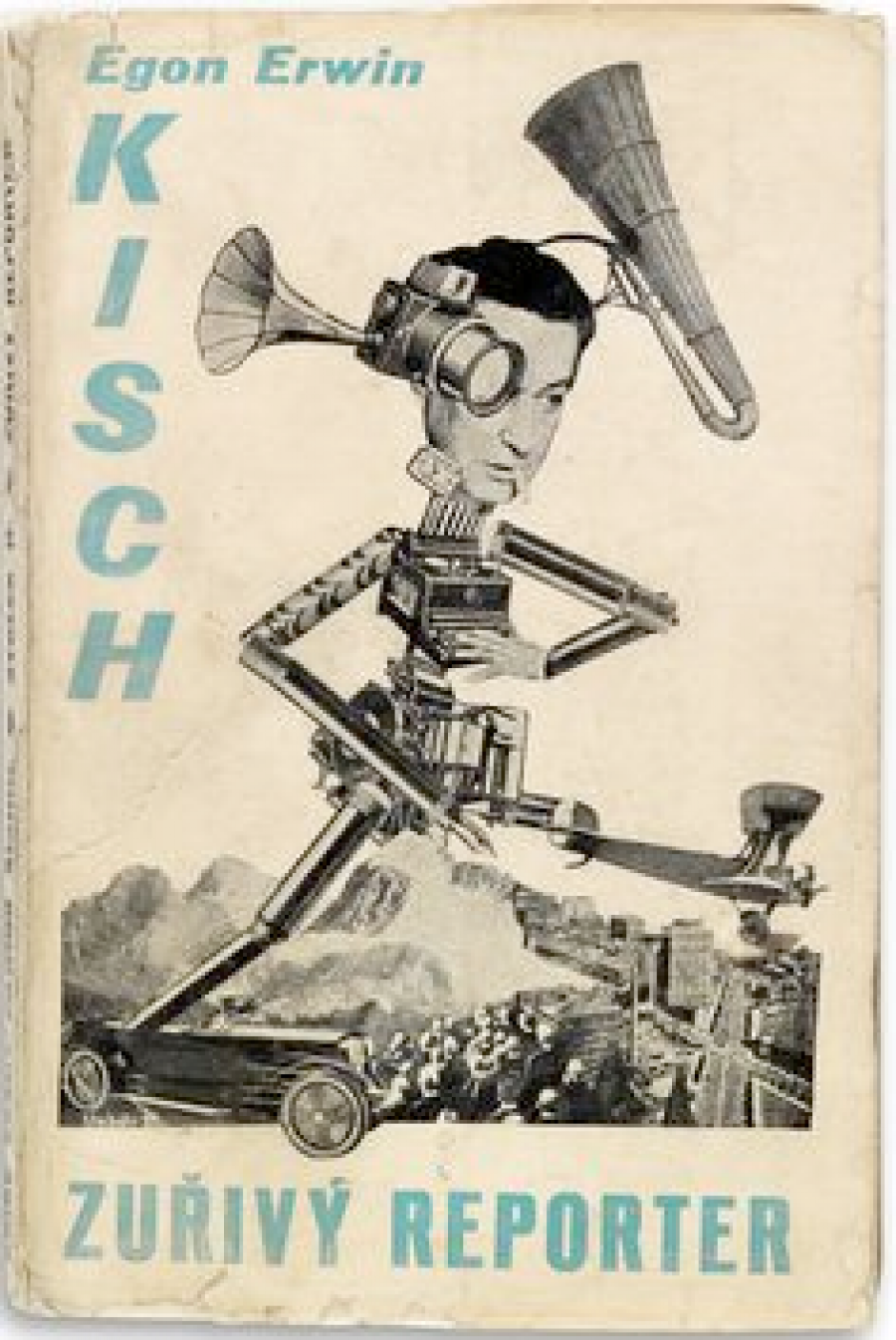

McBride showed examples of such images, like a cyborg reporter marching over an urban landscape. “The German-language media environment had a higher threshold for visual violence and for images that tamper with the human body,” she noted.

Photography was an important aspect in montage because it allowed copies and thus the recombining of copy fragments, “The moment of perception was mediated by technology, so that the perception could be independent of storytelling or of any meaning we attributed to particular fragments,” she said.

Shock was also an important component of montage, she said. “It entails a separation of the moment of perception from the moment of meaning. Montage is sustained by the impact of visual forms that are registered independently of the meanings they are made to support: a shock effect.”

McBride’s interests include 20th-century German literature and culture, and aesthetic theory since the 18th century. She is also the author of “The Void of Ethics: Robert Musil and the Experience of Modernity” and “Legacies of Modernism: Art and Politics in Northern Europe, 1890-1950,” co-edited with Richard McCormick and Monika Zagar.

Linda B. Glaser is a staff writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.

Image: Cover of 2nd Czech Edition of Egon Erwin Kisch’s Der Rasende Reporter, 1929; Photomontage by Umbo (Otto Umbehr)