When the United Nations and other international players rebuild war-torn countries, they frequently require that women have greater representation in the country’s security forces. The idea is integrating women helps improve peace and security for everyone.

But critics of these gender-equity reforms often suggest that women harm the cohesion of the police force.

A new study shows those critiques don’t hold true – and suggests in fact the addition of more women could improve the police force’s cohesion. The study also shows when more women are part of a police unit, they are more likely to speak up and participate than if there were fewer women in the unit.

One of the first experimental studies to assess the effects of gender composition in police force – in this case, the Liberian National Police – the research has implications for other weak, war-torn states where gender reforms are increasingly the norm.

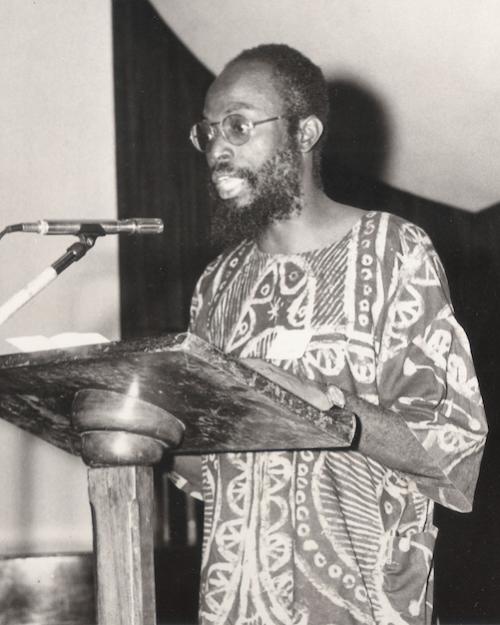

“There’s no harm in including women in these forces, and we actually find evidence that having all-female units or more women works differently but perhaps, in some cases, better,” said lead author Sabrina Karim, assistant professor of government, an expert on gender and postconflict state-building. “There is a difference and it’s a good difference: When women outnumber men, they’re more likely to participate in the group and have their voices heard.”

The paper, “International Gender Balancing Reforms in Postconflict Countries,” was published May 31 in International Studies Quarterly.

Karim and her colleagues partnered with the Liberian National Police to understand how these internationally imposed ways of state-building were affecting their work. They set up a “lab in the field experiment” in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, in 2013, 10 years after the country’s bloody second civil war had ended and Liberia had become a test case for the United Nations’ peacekeeping gender reforms.

Karim and her colleagues tested how the inclusion of women affected three factors that are crucial to maintaining security: how well the police officers work together to achieve a task (unit cohesion); how police groups achieve tactical objectives (operational effectiveness, specific to sexual violence); and the norms that welcome contributions from all able participants (egalitarian norms).

The researchers divided the Liberian National Police into 102 groups of six officers. Each included a randomly assigned number of women; some groups had no woman, while others had as many as six. The groups were asked to complete tasks that measured key factors affecting security. The tasks included cooperative activities, such as building a free-standing tower with only newspaper and masking tape, and deciding whether or not to anonymously give any of the $300 Liberian dollars (approximately $2 U.S. dollars) they received to another group. In another task, the officers were asked to memorize crime scene photos that included possible sexual or gender-based violence; they then wrote a crime scene report, in which they identified – individually and then as a group – what crimes they thought occurred as well as other information that goes into a crime report.

Overall, inclusion of women helped to align the beliefs of individuals and of the group, suggesting more cohesion in the group. When women were in the majority, each individual’s preferences tended align with those of the other officers. “They appear to be able to influence the group more,” Karim said.

And women were more likely to speak up and be active in groups that contained more women, she added. “Their full participation isn’t being felt if men are present. But if you’re in an all-female unit, then you’re reaching your full potential when it comes participation.”

The study found no evidence that simply adding more women increased the unit’s sensitivity to sexual and gender-based violence; that would likely be remedied with professional training for all officers, Karim said. And simply including women didn’t improve men’s beliefs about women’s roles in policing. In some cases, the researchers found an “intrusiveness effect,” where men participated more and were less collegial when they were outnumbered by women.

The study is relevant for countries where similar gender reforms continue with international help, such as Mali, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Kosovo and Bosnia, among others.

“As international actors are pushing for gender reforms in the security sector, it’s important to know that there are positive effects,” Karim said, “and there doesn’t appear to be any major negative effects for cohesion within the security forces.”

That said, women in these male-dominated roles are still likely to face discrimination and sexual harassment, depending on the culture of their country, Karim said. “Their experience is not dissimilar to women in any place where they’re still not the majority.”

Karim’s co-authors are Michael Gilligan of New York University, Robert Blair of Brown University and Kyle Beardsley of Duke University.

This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.