In labs for the class Mushrooms, Molds and More, students are discovering fungi in their areas and sharing photos of them via Instagram and using online resources to identify mushrooms.

And in the class Hands-On Horticulture for Gardeners, Professor Marvin Pritts has asked students to design their own experiments, such as determining whether music helps plants grow, or what the best method might be for propagating Pothos, an ivy, or how to make natural plant dyes.

The coronavirus pandemic has forced Cornell instructors to rethink how they teach lab classes, as remote learning has created special challenges for courses considered more hands-on, collaborative and experiential.

Sue Merkel, associate director of the Office of Academic Programs in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) and a senior lecturer in microbiology, recently led two faculty discussions on how to shift a lab class to a remote teaching environment.

In order to make the transition, she advised instructors to avoid trying to convert an established course to an online format, said Merkel, who has taught at Cornell for 28 years.

Instead, she advocated designing backward. “I set up a framework of trying to encourage [instructors] to focus on their goals first” and what they want students to get out of a class, she said.

Physicist Natasha Holmes, the Ann S. Bowers Assistant Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences, agrees. Teaching labs remotely, she said, “gave us this opportunity to really pause and think about what are our goals for the students” and to strip a lab class down to what is essential.

The mission for many classes at Cornell is to teach students critical thinking, as opposed to learning specific techniques, Merkel said, which makes running a remote lab a little simpler.

“We’re really trying to train students how to use experiments to answer questions and to critically think through problem solving data analysis,” she said. “If you look at it this way, I think it gets a little more manageable.”

Planning a course without access to equipment and organisms has forced instructors to look for alternatives. Instead of teaching hands-on techniques like polymerase chain reactions (which copy and amplify small samples of DNA) or Gram staining (to identify bacteria), teachers could have students read about a process and then ask them to explain what might happen to results if a step were skipped, or explain how to troubleshoot a hypothetical problem.

Holmes, a discipline-based education researcher, coordinates an Active Learning Initiative program for the introductory physics lab courses for engineering and physics majors. She said studying electricity and magnetism is particularly challenging when students lack access to lab equipment. She and colleagues have looked into online simulations and phone apps. The Center for Teaching Innovation has provided many resources, she said, and she belongs to a number of email groups within the national physics community where people are posting suggestions for teaching labs.

Online degree programs, including those in nursing and professional societies, have provided useful strategies and tools during this period, Merkel said. The American Society for Microbiology, for example, has “reams and reams of recommended resources from people who have been teaching online for decades,” she said.

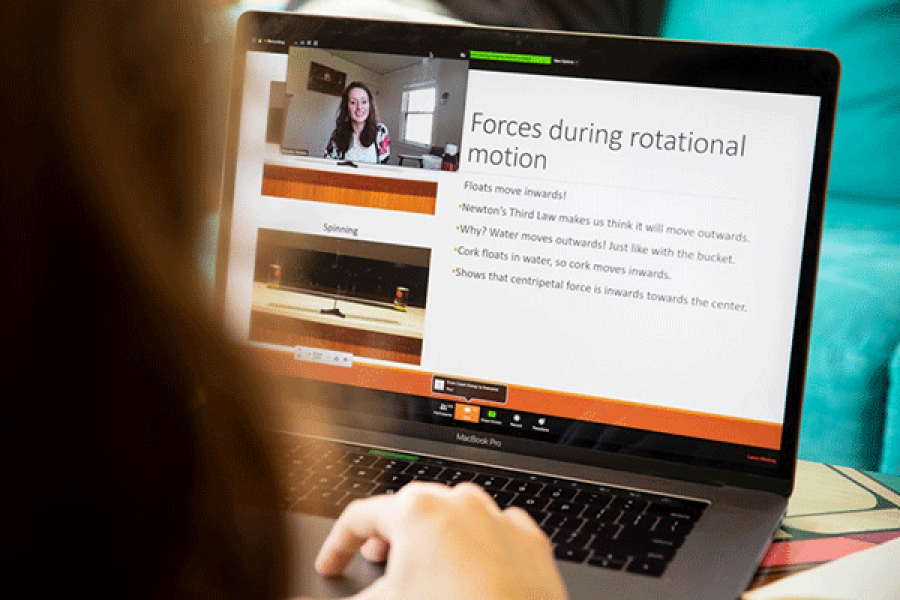

Natasha Holmes leads a remote lecture for her course Physics of the Heavens and the Earth from her home during the first week of virtual instruction.

Locally, Merkel and other faculty started a resource page on Google Docs, where instructors have added links to Cornell apps on demand, instructional videos, datasets, virtual labs, images and case studies. There are large national databases for genetic sequencing data or ecology field datasets, for example, which the public can access and instructors can use to create exercises for analyzing them.

Holmes is taking advantage of basic tools and apps found in cellphones.

“One of the things we’ve been really excited about is getting students to design their own experiments,” she said. “There’s a ton of amazing physics sensors in your phone – accelerometers and magnetic field sensors and a number of apps that allow you to collect quantitative data.”

She has asked students to work in small groups to come up with experimental designs using available tools and items in their homes.

For example: One group of students is testing how the force with which an object hits the floor varies based on the object’s surface area – but they’re using their phone’s microphone to measure the sound produced during the impact as a proxy for the force.

Kelly Lyboldt, a veterinarian and lecturer in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), is the course leader of Function and Dysfunction. This 16-credit foundation course teaches physiology, pharmacology, clinical pathology and pathology to first- and second-year veterinary students. She and her colleagues are trying web-based technology to solve some of their issues.

Under normal circumstances, the class is divided into small groups and each group is assigned a faculty member. Utilizing problem-based learning, they analyze case studies; they use a whiteboard to draw anatomical and functional diagrams, make lists, flowcharts and concept maps.

Currently, each group of eight students is assigned their own Zoom meetings. Zoom whiteboard is used for collaborative drawings. Images and documents for cases are uploaded to Canvas homepages for groups to work through. Google Docs allows students to collaborate in real time, and Lucidchart visualization software lets them build flowcharts, also in real time.

CVM information technology specialists have quickly trained themselves on all the technologies and sit in on sessions.

“Faculty and students are actually really impressed by the functionality of some of the technology, and we may continue to use it in the course even after students return to classrooms,” Lyboldt said.

One silver lining, Merkel said, is that remote teaching has created opportunities for instructors to evaluate the most essential elements in a course and brainstorm new ways to teach.

“Any time you are forced to redo or reevaluate a course,” she said, “you always end up with a better course just because you’re thinking about it.”

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.