Although he was hailed as one of the leading organists of his age, George Frideric Handel – composer of dozens of operas, hundreds of chamber works and many oratorios – wrote few solo pieces for the King of Instruments.

Undaunted, organist and keyboard expert David Yearsley, the Herbert Gussman Professor of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences, has configured some of the composer’s greatest works into pieces for solo organ in his new album, “Handel’s Organ Banquet.”

Recorded on the Cornell Baroque Organ, funded by the Cornell Center for Historical Keyboards, and produced by Cornellian-run False Azure Records, the album includes first and last tracks from Handel’s “Messiah,” with selections from his operas and oratorios, concertos and sonatas in between.

“I’ve added pedal parts, extra voices, cadenzas and other conceits that are demanding but, I also hope, delightful to listen to,” Yearsley said.

The College of Arts and Sciences spoke with Yearsley about the album.

Question: How did you choose the pieces to include in “Handel’s Organ Banquet,” and what was your process of reimagining them for the organ?

Answer: Handel had a knack for coming up with great tunes – and also for stealing them, then riffing on them in his inimitably creative way. With some imagination, one can transform almost any of his music into worthy organ works. My choices from this larder of wonder were motivated most often by what I thought would sound fun on the organ and feel good in the arms and legs. This is workout music for the mind and the body.

Long ago, I became enthralled by Handel’s penultimate oratorio, “Theodora,” especially by two of its arias as I had heard them sung with profoundly expressive conviction by the late American mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. Undertaking this album allowed me to pay tribute, however pale, to her radiant musicianship and humanity.

More hedonistic were the pleasures derived from various favorite sonatas and a concerto grosso and the celebrated aria “Lascia ch’io pianga” from Handel’s first London opera of 1711, “Rinaldo.”

Spoiler alert – there is a bonus track, my own improvisation on the opening theme of the Hallelujah Chorus.

Q: What makes food and feasting a fitting theme for a collection of Handel’s works?

A: Handel had a huge appetite for food and life, so let him feast on his works to the ringing sonorities of the organ, itself a gourmet feast of sonic possibility and power.

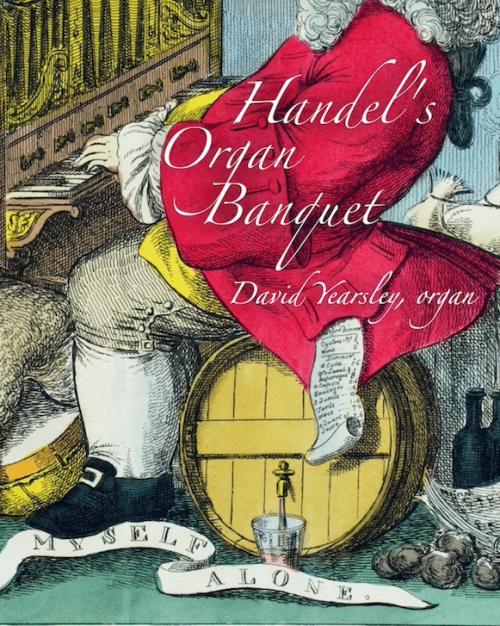

Handel was pictured at the organ only once and in far from flattering fashion. After being invited to the composer’s London house for supper, the expatriate French artist Joseph Goupy produced an infamous caricature of Handel as a hog-headed organist surrounded by a stupendous assortment of victuals and libations. (We use a version of this image on the album cover.) The guest was not impressed by the fare he was served and was even more nonplussed by Handel’s frequent disappearances from the dining room. Goupy eventually sneaked after his host and found him in the kitchen, stuffing his face with far better food than he’d offered his visitor. The artist’s damning image of Handel was a thank-you card for a bad time.

Organ dedications – like ours at Cornell back in 2011 – have for centuries been celebrated with feasts. In Germany, the quantity of beer to be supplied at the banquet could not be less than that contained in the largest organ pipe. We had a special organ beer brewed to celebrate our project’s completion and drank the stuff in quantity at a lavish dinner after the final dedicatory concert.

Q: Why did you choose the Cornell Baroque Organ as the instrument for this venture?

A: The tonal resources of our instrument were based directly on a famous organ that once stood in a Royal Palace in Berlin that Handel visited. The Cornell Baroque Organ has a robust pedal that makes for a proper workout station for the feet. It has plenty of power for Handel’s big choruses, as well as an abundance of color stops ideal for his chamber works – an oboe, flutes, viola da gamba and more. The possibilities are endless and always surprising.

Handel would have loved this organ, and I would be thrilled if he suddenly reappeared from the eighteenth century, stomped into the organ loft, shoved me off the bench and showed me how it is really supposed to be done.