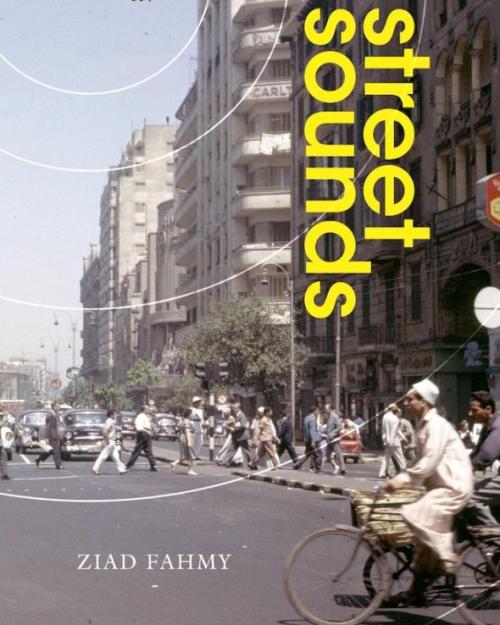

Ziad Fahmy, professor of modern Middle East history in Near Eastern Studies, College of Arts and Sciences, won a 2021 book prize from the Urban History Association (UHA) for “Street Sounds: Listening to Everyday Life in Modern Egypt” (Stanford University Press). Fahmy’s book was recognized in the UHA 2021 virtual award ceremony for Best Book in Non-North American Urban History.

In “Street Sounds,” Fahmy examines the changing soundscapes of urban Egypt, highlighting the mundane sounds of street life, while listening to the voices of ordinary people as they struggle with state authorities for ownership of the streets. Fahmy spoke with the Chronicle about the book.

What were your thoughts upon receiving the Urban History Association book prize?

I was of course very exciting to receive the 2021 Urban History Association book prize.

In many ways it's a vindication of all the hard work that goes into to such a long-term book project. This is especially true when writing this sort of book, which deals with a fairly novel approach and methodology. Because many historians of the modern Middle East tend to be a methodologically conservative lot, there was some resistance and skepticism about this project from a few traditionalist historians.

What inspired this line of research and writing? What can the sounds of the street tell us about everyday life in modern Egypt?

The initial idea for "Street Sounds" came about in early 2011, as I was finishing the final revisions of my previous book [“Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture,” Stanford University Press, 2011]. Because in my first book, I was dealing primarily with recorded music, vernacular theater, colloquial poetry, and other aural sources, I was more consciously aware of the importance of sound and listening to not only the project at hand but more broadly to history writing in general.

Also, a bit of good luck intervened: in 2012, the theme for Cornell’s Society for the Humanities, was: “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics.” My fellowship at the society for that year was really instrumental in exposing me to sound studies form a variety of different disciplines. During my year at the Society, my readings, weekly seminars, and almost daily discussions with the other fellows from various academic disciplines was instrumental in forging my ideas about sounds and soundscapes. The late Trevor Pinch (Science & Technology Studies), in particular, was an inspiration and an encouraging voice to me and to the other fellows.

“Street Sounds” acknowledges the obvious fact that that we live in a multisensory world and of course so did the people of the past, So the broadest claim the book makes is that writing a history that takes account of this multisensory environment can only enrich and nuance our understanding of everyday life. As the book reveals, a sensory approach to the sources uncovers a great deal more about what happened at the ground level. So, in a way, it functions as a micro-historical tool that gets us closer to the streets and street life.

The soundscapes of many (if not all) cities changed dramatically during the 20th century: how did these changes in Egypt in particular lead to a political struggle with state authorities?

The book is a cultural and social history that examines the sonic impact of modernity on the Egyptian streets.

An important part of the book examines the inevitable contestation between state authority and everyday people in controlling the street. I argue that this tug of war over the ownership of the street was also very much connected to classism and middle-class formation. Similar processes and political dynamics took place in other cities around the world. Cairo and other Egyptian cities were not unique in this regard.

Why is everyday life in modern Egypt an important topic for a book?

The simple answer to this question is that everyday people are generally neglected by historians, and often are left out of historical narratives.

What do you hope your book conveys to the reader who has not been to Egypt?

I hope that both historians of the senses and historians of the Middle East can make use of my book as an example of how to study street life and class formation using a sensory approach.

As to more general non-academic readers who have little knowledge of Egypt, I hope the book conveys to them how similar their own societies are to Egyptian society. The same dynamics that were at play in the Egyptian streets during the first half of the twentieth century were happening elsewhere. Some of the particulars might be different, but broadly speaking, twentieth century “modernity” similarly affected societies throughout the world. Also, I hope that the book broadly conveys to my readers the important role that all of our senses play in determining our place in our environment and in forming our own sense of identity.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.