Electroplating – the process of using electricity to deposit one metal onto another – originated in the 19th century and can be found in everything from pennies to gold-topped cathedrals.

But electroplating is no easy task when you’re creating groundbreaking microscale technology, as Kwame Amponsah ’06, M.Eng ’08, M.S. ’12, Ph.D. ’14, discovered several years ago while trying to fabricate microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) devices at the Cornell NanoScale Science and Technology Facility (CNF). Amponsah is CEO of the startup Xallent, which builds nanoscale software and hardware products to test semiconductors and thin-film materials.

Their fabrication dilemma had Amponsah and his engineers stumped.

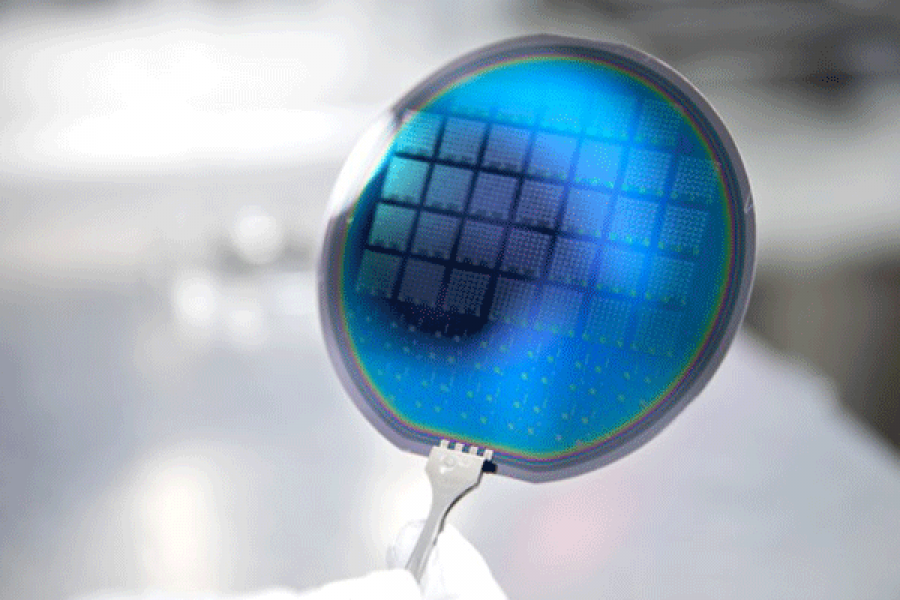

Xallent’s fine pitch probes, fabricated at CNF, are used to test artificial intelligence chips.“We tried to do this kind of electroplating, but we weren’t getting the results that we wanted,” he said. “Then we involved the CNF staff.”

Founded in 1977, CNF enables scientists and engineers from academia and industry to conduct micro- and nanoscale research with state-of-the-art technology and expertise from its 23-member technical staff.

But perhaps the facility’s greatest breakthrough is helping launch startup companies in New York state. Over the last four decades, at least 34 startups have launched at CNF and continue to use its services, with 14 – including Xallent – forming in the last ten years. These companies annually generate about $1.4 billion in funding and revenue.

Amponsah had used CNF throughout his graduate and postdoctoral research in the lab of Amit Lal, the Robert M. Scharf 1977 Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering. Amponsah went on to found Xallent in 2013 with Lal and tech executive Ashish Kumar, M.S. ’93, Ph.D. ’95.

Now as an entrepreneur, Amponsah and his team at Xallent again turned to CNF, where staff members were able to recommend key steps that allowed them to successfully electroplate the MEMS devices.

“It took two months,” he says. “Without the CNF staff, it would have taken us six.”

Xallent saved not only time, but thousands of dollars that would otherwise have been spent on employee and facility costs.

The company also gained a customer: CNF was so impressed with Xallent’s nanoscale probing technology that it purchased a pair of Xallent Nanoprobers – one that fits in an electron microscope (DARIUS) and a bench-top version (SAKYIWA).

“The expertise of the CNF staff is invaluable, and they have a portfolio of machines you might only find at two or three places in the U.S.,” Amponsah said. “That allows us to always be at the cutting edge of research.”

That cutting edge includes tools and processes like electron beam lithography, dry etching, constructing quantum devices, and use of one of the most advanced cleanrooms in the Northeast, if not the country.

Accessible to companies, colleges

Each year CNF hosts approximately 600 users, from small startups to large corporations. Over the past decade, 72 New York companies and more than 100 colleges and universities from around the U.S. have relied on CNF.

While other leading academic institutions have nanotechnology facilities, they generally work with faculty or major corporate clients. CNF strives to be accessible for burgeoning companies, as well, many of which have their roots at Cornell.

“That makes us really special in New York state, but it also makes us special nationally,” said Christopher Ober, the Lester B. Knight Director of CNF. “New startup companies usually can’t access commercial cleanrooms, and if they can, they can’t afford them. Our business model is to encourage people to ask questions. We give free consulting. If somebody comes in, we charge them an hourly rate for a tool, but we don’t charge them for consumables, like other places.”

CNF policy also ensures that users retain all rights to their intellectual property.

Kwame Amponsah used CNF throughout his graduate and postdoctoral research in the lab of Amit Lal, the Robert M. Scharf 1977 Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering.“It’s why startup companies like coming to us,” said Ron Olson, CNF’s director of operations. “Basically, their IP belongs to them.”

The facility operates with funding from the National Science Foundation; the Empire State Development Division of Science, Technology and Innovation, known as NYSTAR; Cornell; and user fees.

This diverse support shapes the range of services CNF provides, including outreach efforts like providing research experience for undergraduates and engaging rural youth who are interested in science and technology through 4-H programs. CNF outreach may soon extend to workforce development.

Jonathan Alden, M.S. ’12, Ph.D. ’15, credits CNF with helping the company he co-founded, Esper Biosciences, raise $430,000 in small-business funding from the National Institutes of Health.

The funding supported Esper’s development of nanopore devices for DNA sequencing. This technology, which grew out of Alden’s graduate work with Esper co-founder Alejandro Cortese, M.S. ’14, Ph.D. ’19, aims to make DNA sequencing so fast and affordable it can be used in doctors’ offices for diagnosing infectious diseases.

“I suspect that one of the reasons I was able to get these grants from the NIH is because I could tell them I have experience using this state-of-the-art facility, and so I can make these devices efficiently and competently,” said Alden, who along with Cortese did graduate work in the lab of Paul McEuen, the John A. Newman Professor of Physical Science in the College of Arts and Sciences. “If I had to convince them that I was going to move across the country and use a different facility I had never tried before, that probably would have lost me a few points, which might have lost me the grant.”

Many startups naturally gravitate to large cities, like Boston and San Francisco, that have tech-friendly venture capital and angel investors. But CNF’s mix of access, equipment and expertise can be just as crucial to attracting investors.

The capitalization value of companies launched at CNF is estimated to be approximately $3 billion.

“My hope, from the start of my Ph.D., had been that I could come up with a technology that I could turn into a company,” Alden said. “Frankly, there’s no way I would have been doing this in upstate New York if CNF didn’t exist.”

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.