As its founding director 20 years ago, Victor Nee didn’t imagine the Center for the Study of Economy and Society (CSES) taking an interest in New York City’s tech economy. The city hardly had one to speak of – on par with Philadelphia’s, and a bit player compared to financial services, real estate or tourism.

Now, New York claims the nation’s second-largest tech economy after Silicon Valley, and the development of regional knowledge economies is one of several primary areas of research focus for the center’s Economic Sociology Lab, supported by graduate researchers and undergraduate assistants.

The work is one of the many crossdisciplinary projects that the center focuses on, bringing together disciplines from sociology to economics to computer science to gain a better understanding of economic markets and economic action.

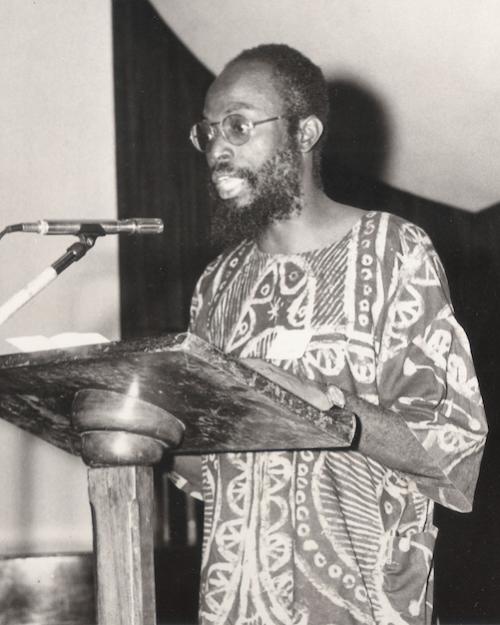

“This research integrates economic sociology with big data, linking that with more classical social science research methods,” said Nee, the Frank and Rosa Rhodes Professor in the Department of Sociology in the College of Arts and Sciences. “So it’s an exciting project, and we are making good progress on it.”

Nee this year has resumed leadership of CSES, which he said has highlighted Cornell’s strength in economic sociology, consistently one of the university’s highly ranked subfields. The mixed-method scholarship of the center’s Economic Sociology Lab extends a sociological approach to the study of economic life, Nee said.

“In any efforts where you have cross-disciplinary research, you have more possibilities for productive intellectual trade, which moves the field forward,” he said. “We’re continuing our tradition of graduate training and undergraduate education in this hybrid field of economic sociology.”

Nee hopes to broaden the Center’s reach and impact through virtual access to its seminar and colloquium series, a shift spurred by the pandemic and further inspired by the late sociologist Robert Merton’s idea of a “university without walls.”

The knowledge economies under study, also including Los Angeles, have benefitted from the tech economy’s shift in emphasis from hardware to software and apps, making it easier for non-engineers to develop disruptive ideas and lead tech startups, Nee said.

In New York, for example, only 10% of the tech workforce has an engineering background, he said. Center research also has examined gender in executive level tech management, finding growing numbers of women, but more often responsible for marketing and communications functions than technology.

In another research project, a working group is examining sources of extreme, billionaire wealth. The key questions, Nee said are what explains why so much extreme wealth is now being made across the global economy, and why is it growing fast, even during the pandemic?

“Throughout human history, great wealth was owned by rulers – the pharaohs of Egypt, the emperors of China, the Mongol empire, the King of England – because they could appropriate wealth,” Nee said. “What is unusual about this period is that most of the great wealth is being made by self-made entrepreneurs, not through inheritance, and they’re growing so rapidly, both in numbers and the size of their wealth.”

Think of names like Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg or Jobs, Nee said, but many more – the Economic Sociology Lab’s dataset of 4,432 billionaires shows significant numbers based in emerging economies such as China and India, with China second to the U.S. in number of billionaires. The two countries couldn’t be more different politically, Nee said, but resemble each other in terms of creating great wealth, with small percentages of those fortunes gained through political connections.

Nee, the author with Sonja Opper, a professor at Bocconi University in Italy, of “Capitalism from Below: Markets and Institutional Change in China,” has spent more than a decade studying the emergence of modern legal-rational capitalism in China, another ongoing CSES project. The Chinese Communist Party could expropriate wealth through taxes or nationalization, Nee said, but has instead encouraged private enterprise and allowed great wealth to flourish.

“It’s a puzzle, and I don’t think any one discipline has an answer to this question,” Nee said. “It’s a different world that we’re living in.”