Professor of music and Bach scholar David Yearsley has assembled a portrait of Anna Magdalena Bach in his new book, fleshing out a member of the Bach family who has been termed “history’s most famous musical wife and mother.”

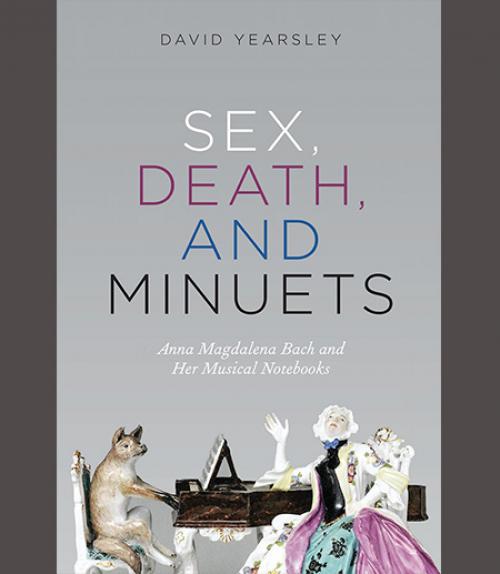

“Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and Her Musical Notebooks” is a cultural history as well as a musical biography of the woman who in 1721 became Johann Sebastian Bach’s second wife.

While she was a talented singer in her time, Anna Magdalena (1701–60) is best known to musicians and scholars by the two musical notebooks compiled and given to her by the composer, in 1722 and 1725. She has been a subject of musicological scholarship (and speculation), novels, dramatic plays and films ever since her 1725 notebook first came into public circulation in the early 20th century.

Domestic life and music in the home as shared by mothers and children in early 18th-century Germany are among the themes of Yearsley’s study.

“The evidence pertaining directly to her life is scant,” Yearsley notes in his prologue, though he goes on to reveal much about his subject’s life and times.

Musical examples from her notebooks abound in Yearsley’s book, and the chapter titles – “Music for Weddings and Beddings,” “Death Every Day: The 1725 Notebook and the Art of Dying” and “On Coffee, Cantatas, and Unwed Daughters” – highlight the idiosyncratic selections that J.S. Bach (1685-1750) made in the music that these gifts to his young wife contain.

A soprano brought up in a family of musicians, Anna Magdalena held a position as a court singer in Cöthen from 1721-23, appearing for occasional special performances with her husband.

Her talent as a singer afforded both prestige and an income “in the musical economy of Lutheran Germany,” Yearsley notes, in addition to her role as wife and mother (she bore Bach 13 children). But, lacking any surviving record of performances in Leipzig, it is assumed that, after those first few years of her marriage, she sang and played the harpsichord in the home.

The notebooks also show Anna Magdalena’s skill as a calligrapher, and her careful hand as a music copyist, from the works by other composers that she added to the pages.

The Bachs were a team, and she would often write out works by Bach for sale or for teaching purposes, or complete the performing parts for cantatas to be sung in Leipzig churches. The first two sections of the B Minor Mass are in her hand in a presentation copy; and a few of Bach’s compositions, such as solo works for cello, survive only in her hand.

Following the composer’s death, Anna Magdalena spent the last 10 years of her life as an impoverished widow, living with her two youngest daughters.

“Anna Magdalena’s afterlife as a symbol, indeed purveyor, of the supposedly timeless family values fostered by musical domesticity elevated her to the status of the most beloved of the Bachs,” Yearsley writes. “[H]er historical persona has exerted a tremendous, if often unacknowledged, influence on the musical lives of millions.”

Yearsley joined the Cornell Department of Music faculty in 1997 and teaches courses on Bach and Handel, music and travel, the organ, music theory, music journalism, and film music. He is the author of “Bach and the Meanings of Counterpoint” (2002) and “Bach’s Feet: The Organ Pedals in European Culture” (2012).

His recordings include “Bach: Six Trio Sonatas” (2015) and “Bach & Sons” (2017), both featuring the baroque organ in Anabel Taylor Chapel. He received a Guggenheim fellowship in 2018 for a book project on Bach as a musical humorist.

This story also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.