As the world’s largest radio/radar telescope when it was commissioned in 1963, the Arecibo Observatory saw countless firsts, from revealing the surface of Venus to mapping ice deposits at the poles of Mercury.

Its discovery of the first known binary pulsar led to the verification of Einstein’s prediction of the existence of gravitational waves and won a Nobel Prize for its discoverers, Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse.

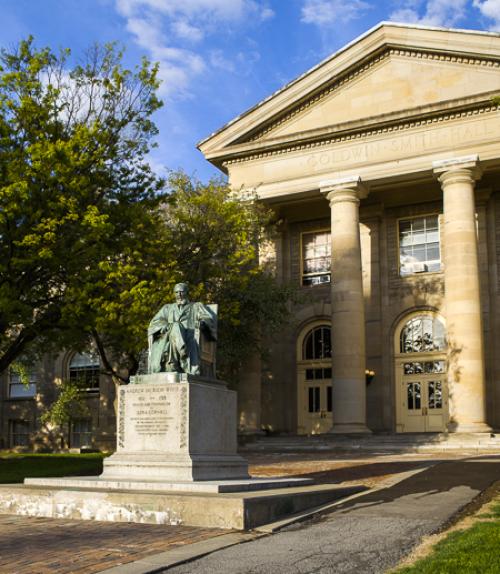

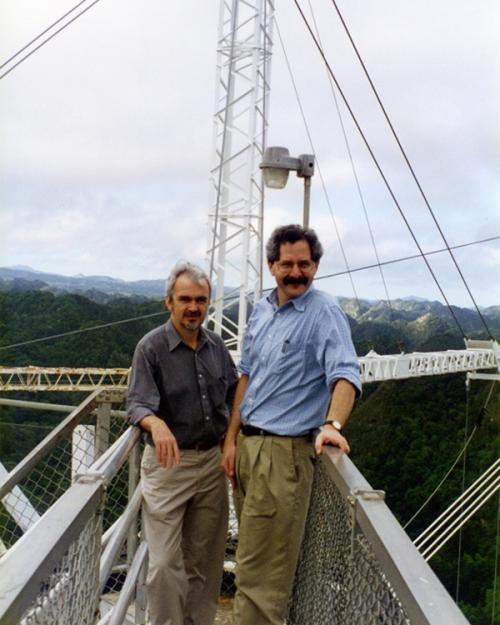

In a new book, “The Arecibo Observatory,” Donald Campbell, Ph.D. ’71, professor emeritus of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences, recounts the history of Arecibo from construction to its last days under Cornell’s management in 2011. Campbell served as director of the Arecibo Observatory, from 1981-87, and as director of Cornell University’s National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center (NAIC), which managed Arecibo, from 2008-11.

Campbell first arrived at Arecibo in February of 1965, having just finished his Master’s degree, as one of the radio astronomy specialists recruited from Australia to augment the then small scientific staff. After a year, Campbell decided he would like to finish his Ph.D. at Cornell.

“I called up Ed Saltpeter, the graduate field representative for astronomy, and he essentially said, sure, come in January. Just like that. Those were the days,” Campbell said.

One of the first courses he took was given by Carl Sagan on the planets. Campbell kept his notes from those Sagan lectures and recently donated them to the Carl Sagan Institute. For his thesis, Campbell continued his research at Arecibo, primarily on imaging the surface of Venus beneath its thick cloud cover.

Campbell spoke with the Cornell Chronicle about the book.

Question: What was Arecibo intended to do?

Answer: Arecibo was built to study the Earth's upper atmosphere, the ionosphere, using radar. At that time, very little was known about this region, especially above about 200 miles.

In the 1950s, the Advanced Research Project Agency (ARPA), which funded the telescope’s construction, had a strong interest in ballistic missile defense, Project Defender. It was thought that incoming ballistic missiles would possibly leave a wake in the electron density distribution as they went through the ionosphere at a high altitude, and that the proposed telescope could, potentially, detect those wakes. In addition, it could also – this was semi-classified at the time – potentially detect nuclear explosions in space. In 1961 after about a year of construction, the increasing cost and delays caused staff at ARPA to question whether the project was worth it and the project was almost canceled.

Studying the ionosphere was the main aim, but William Gordon, professor of electrical engineering, who conceived the idea for the telescope, found the funding and oversaw the construction, pointed out that the telescope could also be used to bounce radar signals off the surface of Venus, and possibly Mars and the sun, and study radio emissions arriving from distant space.

Q: What research stands out from your time at Arecibo?

A: We obtained the first images of the surface of Venus with high enough resolution that you could actually say, that's an impact crater, that's a volcano. Little was known about the surface of Venus under its dense cloud cover and we imaged about 25% of the surface of the planet. NASA, which was providing some funding, was very pleased with that. The National Science Foundation took over the funding of the Observatory in late 1969.

Martha Haynes [Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in Astronomy Emerita, A&S] and others were heavily involved in utilizing the telescope to study atomic hydrogen, the main gas constituent in our and other galaxies. She and the late Riccardo Giovanelli [professor emeritus of astronomy, A&S] came up with very interesting results. They received the Henry Draper Medal from the Academy of Sciences for “the first three-dimensional view of some of the remarkable filamentary structures of our visible universe.”

The discovery of pulsars, rapidly rotating collapsed stars, in 1967 really put Arecibo on the map, because Arecibo was the perfect telescope to study them. It was very sensitive and was equipped to detect very short radar pulses, which are not that different from pulsar pulses. We had all the digital equipment that could sample the incoming signals at microsecond rates. This led to the discovery of the first binary pulsar and also to the discovery by Alex Wolszczan of the first known planets around a star, admittedly a collapsed star, not an ordinary one.

Q: How did Frank Drake’s famous message to the stars come about, the first and so far only deliberate radio message to extraterrestrials?

A: Frank became interested in SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, when he was on the staff of the Greenbank Radio Observatory in West Virginia. He initiated Project OSMA, the first serious search for extraterrestrial intelligence. He continued to have a strong interest after joining the Cornell faculty and, of course, Carl Sagan was also interested. Between 1972 and 1974 the telescope’s reflector was resurfaced to allow higher frequencies and a second high powered transmitter installed primarily for planetary observations. Frank decided that since we’re going to have this powerful radar transmitter on the telescope, we’d use it to beam a message to demonstrate that this capability existed. The message went to a cluster of stars about 25,000 light years from Earth, so it will be some time before a response will be received. It was sent during the inauguration event for the upgraded telescope.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.