The black, faux-leather book cover declares “The American Fraternity,” and nothing else. The title page reads only “Ritual of Initiation.”

“The American Fraternity” is an almost verbatim reprint of a University of California, Berkeley, fraternity’s secret ritual manual, interspersed with photos Andrew Moisey took at the fraternity over seven years. The book is intended to represent the living culture of the fraternity but is not a work of photojournalism claiming to capture the whole: It is intended “as an experience – a work of art,” said Moisey, Cornell assistant professor of history of art and visual studies.

He found the ritual book on the floor of the fraternity house after it closed down. The abandoned building felt like a ruin, he said, and finding the ritual manual made him feel like an archaeologist. The book – and photos – as artifacts of fraternity culture became the theme around which he structured the work.

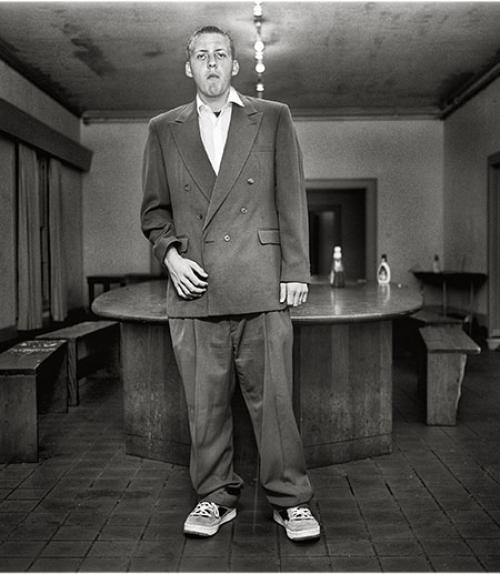

The text of the ritual manual emphasizes honor and chivalry; the photos show a culture of excess. “Those are the twin parts of an institution,” said Moisey. “In the case of a fraternity, they’re making promises about personal purity and honor, all these very high ideals that America often carries around the rest of the world, holding up itself as a shining light. And then there’s the experience, the reality.”

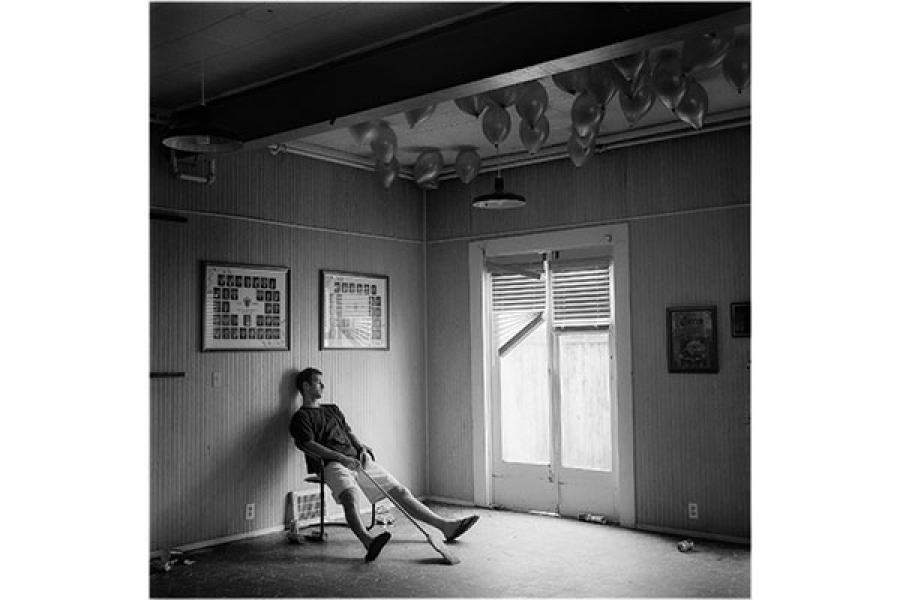

An image from "The American Fraternity." Copyright: Andrew Moisey

Tucked into the book’s front cover is a folded reprint of a paper written by a member of the fraternity for his anthropology class, “How to be a Man amongst Brothers.” The paper, said Moisey, “will be funny and possibly shocking to some people. But it’s also an artifact that speaks to the reality of fraternities – which is that if you live in a fraternity, your values are going to be more shaped by the fraternity than they will be by the college itself.”

Moisey situates fraternity culture squarely in the center of American leadership. At the beginning of the book he lists the U.S. presidents with their college fraternal orders, along with photos of those presidents from their college days. At the end of the book he lists vice presidents, cabinet members, CEOs, congressmen, bishops and Supreme Court justices.

“I think that what the book captures is a college culture that becomes foundational to American leadership and American culture in general. That’s where the rub of the book is for me,” he said. “I want people to look at the book and wonder about the stereotype or the reputation that fraternities have, and then ask themselves is there any connection between the reputation Americans have around the world and the reputations fraternity men have here? And if so, why does that exist?”

And while Moisey sees the value in fraternities giving members a place to throw off the pressures of society, he also raises the question through his photographs of how easily that relief can lead to collateral damage. “The secret oaths provide a sense of protection,” he said, one reason fraternities exist as secret societies. “But in a society that gives men of a particular standing all kinds of freedoms – men who would be joining fraternities anyway – why do you need an extra level of protection?”

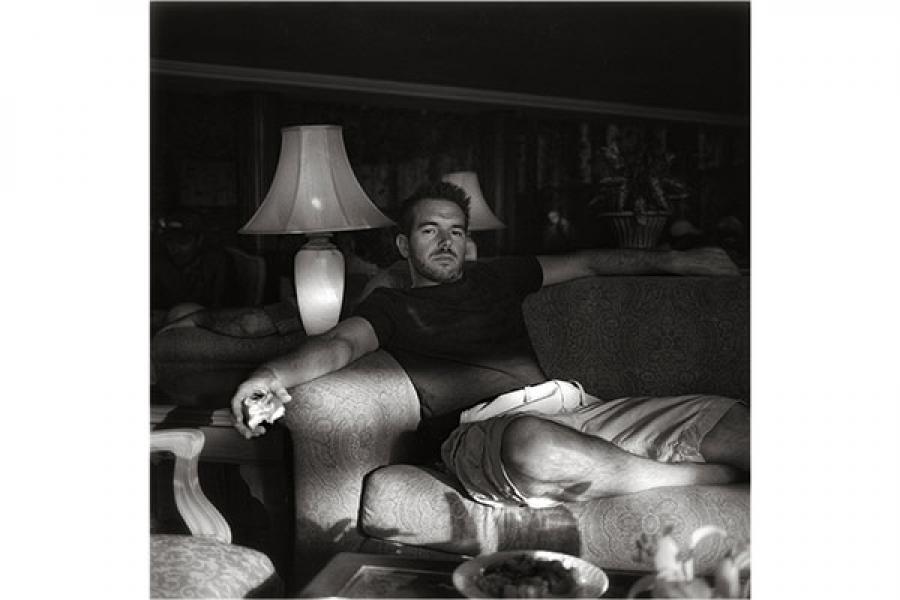

An image from "The American Fraternity." Copyright: Andrew Moisey

Two commentaries are included in the book, but Moisey places them in an appendix at the end so readers first experience the photos and ritual text for themselves.

The first essay, “Girlplay,” is by novelist Cynthia Robinson, the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of History of Art in the College of Arts and Sciences. Moisey wanted a woman’s voice in the book, and he chose Robinson, he said, because “she writes beautifully about really difficult and messy aspects of relationships. I thought that Cynthia could speak to some of the situations that you see in my book about men and women better and more compellingly than I could. Her essay speaks to the broader culture that the book addresses.”

The second essay, “Afterword,” is written by Nicholas Syrett, author of “The Company He Keeps: A History of White College Fraternities.” Moisey especially wanted Syrett’s essay, he said, “because his was the most well-researched opinion I could possibly find."