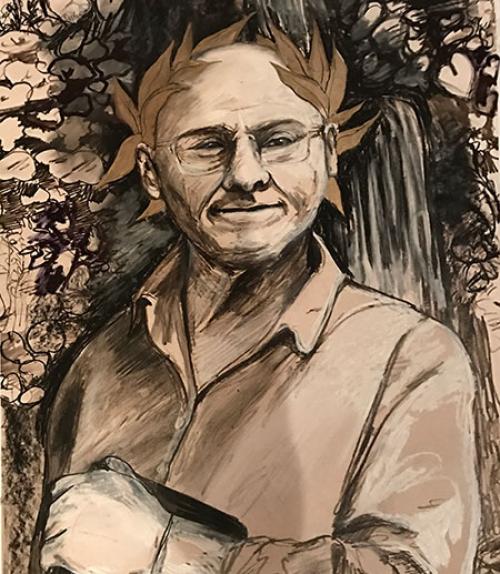

Frontispiece of “Quasi Labor Intus: Ambiguity in Latin Literature,” created by Lucy Plowe B.F.A. '20

Legal capriciousness, or hog soup? The Latin “ius verrinum” could mean either, as the new volume “Quasi Labor Intus: Ambiguity in Latin Literature” explains.

Co-edited by Michael Fontaine, Charles J. McNamara, William Michael Short and including a contribution by Rachel Philbrick ’07, the volume is a collection of papers in honor of American priest and friar Reginald Foster, who was the Latinist for four popes. Foster was succeeded at the Vatican by Dan Gallagher, now Professor of the Practice in the Department of Classics, in the College of Arts and Sciences.

As students know all too well, the Latin language is beset with ambiguity; a single word can look like three, four, five or even nine different things. And worse, even the simplest of Latin sentences may contain ambiguity, said Fontaine, professor of classics and associate vice provost. That’s true whether it’s “ambiguity of morphological and syntactic analysis, of lexical meaning, of grammatical terminology, of argumentation [or] wordplay,” the co-authors note.

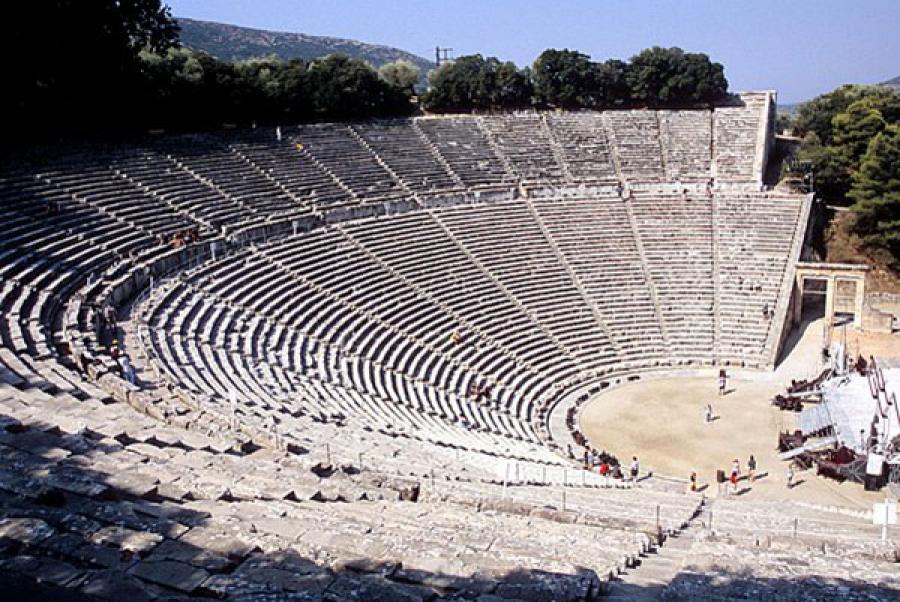

Fontaine’s chapter, “A Cute Illness in Epidaurus: Eight Sick Jokes in Plautus’ ‘Gorgylio (Curculio)’” explores previously unnoticed humor in Plautus referencing “disease, disability, deformity, diagnosis and treatment.” The approximately 2,200-year-old play is set in Epidaurus, famous for the sanctuary of Asclepius that attracted pilgrims seeking healing from throughout the Greek world. Fontaine calls it “a holistic health center” and the jokes it inspires, he said, reveal surprising facets to Roman attitudes toward illness and healing, including their unmistakable skepticism toward faith healing and miracle cures.

The Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus in the Greek city of Epidaurus, located on the southeast end of the sanctuary dedicated to the ancient Greek God of medicine, Asclepius.

But neither did Romans necessarily embrace the new alternatives offered by the Hippocratic doctors with their humoral theory, purportedly rooted in science.

“These attitudes reveal that the status and credibility of medicine in the time of Plautus’ ‘Gorgylio’ was anything but a settled question,” writes Fontaine. “The resistance to acupuncture in Western medicine suggests something of Roman attitudes toward these Greek novelties.”

The eight jokes Fontaine highlights entail puns and ambiguities in the language, with fish playing a major role. The fish jokes are multileveled, explains Fontaine. Fish were the height of luxury to the Greeks, which explains why it was used as a metaphor for seduction or sensuality: Courtesans were often given fish names. Fish addiction was also considered an actual mental or social illness, writes Fontaine. “Today we have alcoholism, but in ancient Greece fishaholism was a bona fide thing,” he said.

“Fish names tend to be inherently ambiguous, and hence potentially always funny. They are regularly drawn from other and more familiar domains, especially domestic or bodily: bird names, plant names, body parts and so on. That makes them ripe for generating puns or clever associations,” Fontaine writes. “Several websites dolphinately agree,” he added with a grin.

Philbrick is a lecturer at Fordham University. Her chapter, “Praeteritio and Cooperative Ambiguity,” explores the rhetorical trick of saying you won’t talk about something while talking about that very thing, e.g., “I'm not going to discuss this man’s sexual history here in court, or how he was sleeping with 17 different women at the same time, because that’s irrelevant.”

This technique was commonly taught in Roman law schools, and Philbrick examines Cicero’s use of the rhetorical device. The strategy, she argues, “hinges upon an audience that is cooperative and willing to read ambiguity into a statement that is unambiguous.”

It’s an ancient technique much used by politicians today, Fontaine noted.

The volume also includes a contribution by an undergraduate: The frontispiece portrait was painted by Lucy Plowe, B.F.A. '20, who is in Italy for the College of Art, Architecture and Planning’s Cornell in Rome program.

This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.