This is an episode from the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast's fourth season, "What Does Water Mean for Us Humans?" from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about the relationship between humans and love. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Tuesday through the spring semester.

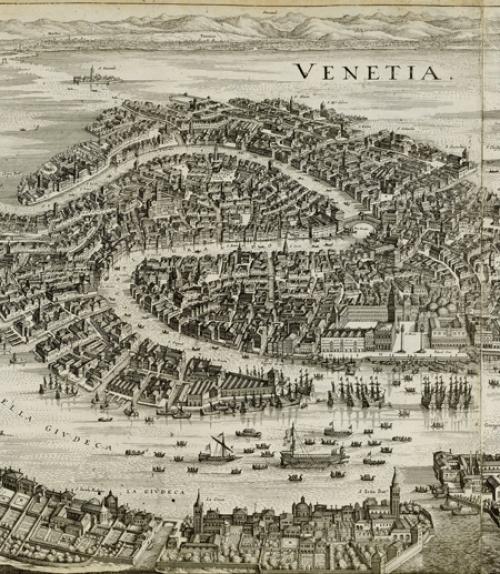

We might not realize that European Renaissance culture had everything to do with water. Think about Venice, situated on the Adriatic Sea, with access to Asia as well as to all of Europe’s waterways. That incredibly cosmopolitan city shaped art, music, and literature – and its export throughout Europe—by way of its watery routes.

Venetian waterways afforded major conduits for trade and commerce, but also for literary and artistic production. Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century improvements in shipbuilding and navigation brought great wealth to Venice. But for all its affluence, Venetian culture was not the glittering carnival that we envision today. It was restrained and even puritanical, governed by families of a hereditary nobility who directed their artistic patronage towards expressions of pious sentiment.

The rise of an entrepreneurial class of merchant and banking elites in Venice, including German, Dutch, French, and Spanish traders working there, eventually diminished the nobility’s influence and replaced its religious culture with a secular and worldly-wise one. German merchants, for example, brought to Venice new techniques of oil painting (think of Titian and Tintoretto) and of polyphonic music (think of motets and madrigals), exported westward through the waterways of Italy and the Mediterranean Sea to Spain and France.

In literary influence, by 1500, the Venetian publishing industry had become Europe’s largest, owing to its vast outlets for distribution. Its editors circulated Europe’s first modern bestsellers, soon translated into languages that excited, among others, Rabelais, Spenser, Shakespeare, and Cervantes.

Renaissance Venice by itself produced two first-rate poets whose work proved remarkable on several fronts. First, without aristocratic patronage, they thrived by attaching themselves to the private salons of wealthy merchants. Second, both got their work published to wide acclaim. Third, somewhat (but not entirely) unusual, both were young women.

One was Gaspara Stampa, the daughter of a merchant-jeweler’s widow. When she died prematurely in 1554, her sister arranged to publish her manuscripts. Of her 310 poems, 200 concern the poet’s unrequited love for a nobleman, exposing class differences that forbade their marriage. Soon after consummating their affair, the nobleman “ghosted” her, refusing to acknowledge her existence.

But don’t just think of Stampa as a romantic figure, floating in a gondola with her lover down the Grand Canal – she was also a canny professional, shaping her poems for a diverse readership in and beyond Venice. Her sister was an entrepreneur, bundling Stampa’s poems for distribution across the waterways of Italy and northern Europe, where, even in 1912, the German-language poet Rainer Maria Rilke commended her work to modern readers.

The other remarkable writer was a satirist named Veronica Franco, a professional courtesan who attracted well-heeled lovers and, in her unashamed poems, kidded the pants off them (so to speak). A prominent patron sponsored her publication in 1575, which enabled a recognition of her that was revived in a 1998 Hollywood film titled Dangerous Beauty.

So, Renaissance Venice built a complex culture that wouldn’t have been possible without its imports and exports over canals, rivers, and seas. It is water, then, that had carried those cultural riches down to us today.