In the late nineteenth century, revolutionary Chinese students looked to theater as a way of expressing their desire for change, according to Kun Huang, a doctoral candidate in comparative literature. For inspiration, they turned to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an American novel from 1852 written by the white abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe, adapting the novel into a play in 1907. They focused on the novel’s portrayal of oppression, injustice, and resistance and aligning its portrayal of Black enslavement to Chinese struggles at the time. This play is often considered to be the origin of modern Chinese drama, Huang says in a Cornell Research profile.

“The Imperial dynasty in China was being challenged from inside and outside. To cope with the political crisis, reform-minded student artists incorporated the enslaved Black figures from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to inspire their fellow citizens to rescue the nation from its impending demise,” Huang says in the piece.

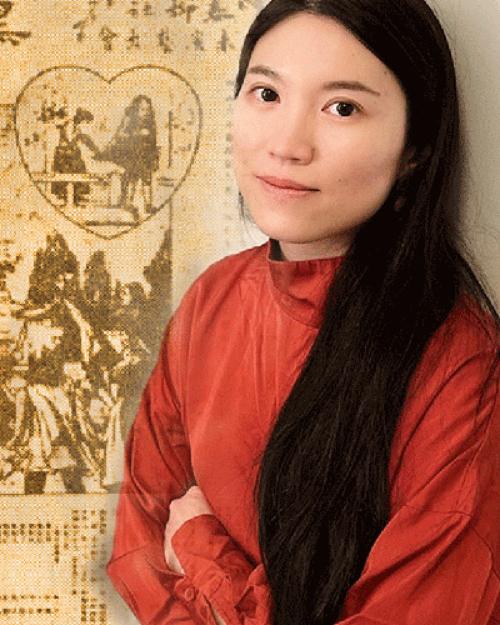

Huang, who is fascinated by how ideas about Blackness can seep through national boundaries and influence movements thousands of miles away, studies the translation of global ideas of race and Blackness in modern China.

Read the story on the Cornell Research website.