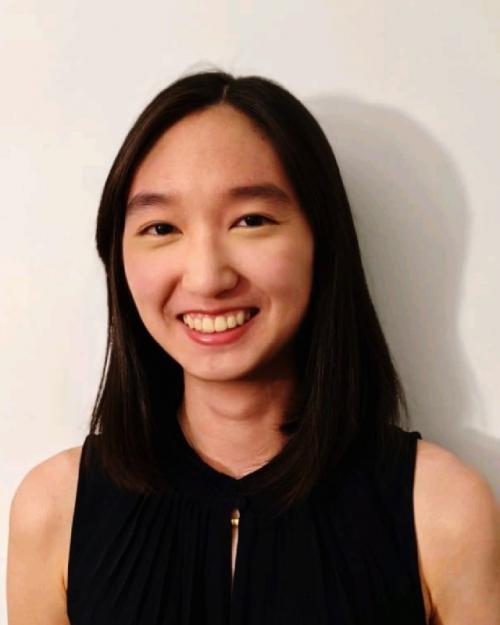

Magical Mushrooms, Mischievous Molds, or PLSCI 2010. It’s a popular class at Cornell, but Eileen Tzng ’22 hasn’t actually taken it. Instead, she has taken it upon herself to study arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, microorganisms that are known to live in the roots of many plants on every continent except Antarctica.

“These fungi can form beneficial relationships with about 80 percent of terrestrial plants. They're really small. They're probably where you live. You don't necessarily realize that they have a lot of significance, so they’re often overlooked,” Tzng says.

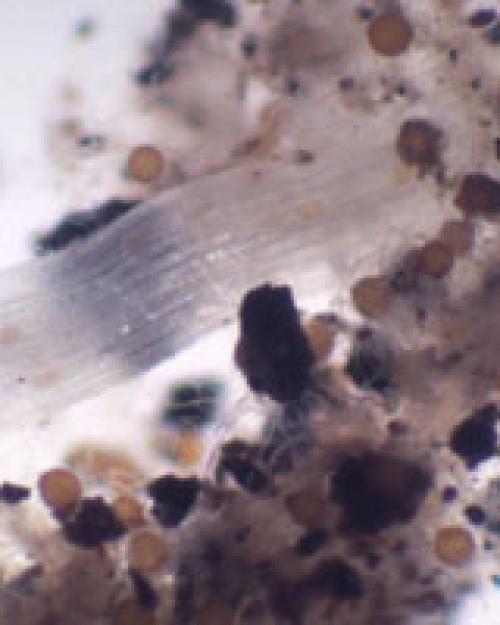

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reproduce through spores that, unlike plant seeds, are composed of a single cell.

“I am looking at how the spores interact with certain bacteria that live in them, or that could live in them, called endobacteria. These endobacteria need to live in the spores, but the spores do not need the bacteria. I want to look at the influence that endobacteria have on the spores and see the deeper connections between the two,” she says.

Endobacteria rely on the spores for a home. But they are not the only organisms that benefit from a relationship with the spores. When spores form a symbiotic relationship with a plant, they can enhance the plant’s drought tolerance and resistance to several soil pathogens, as well as improve a plant’s ability to acquire nutrients.

“Some recent pursuits of this research relate to sustainable agriculture,” Tzng says. “Researchers want to look at how to use spores as a replacement for things like pesticides. It’s a natural alternative to conventional pesticides that could give plants pathogen resistance or boosted nutrient acquisition from the soil. There's also work looking at land restoration, using spores to help some plants grow quicker in deforested areas, improve soil aggregation, and boost the environment.”

Challenges of germination

Given all the uses that spores may have, Tzng, a biology major, wants to discover what the presence of endobacteria means for the spores. In the Teresa E. Pawlowska lab, Tzng measures the effects of endobacteria on spore growth. She knows that endobacteria need the spores, but do endobacteria offer spores anything in return?

She starts with an assortment of spores, some that contain endobacteria and others that do not. She then gently sterilizes all the spores to remove any unwanted bacteria or other microorganisms on the spores’ surface that could interfere with her results.

In a laboratory on the second floor of the Plant Science Building, the spores are placed in Petri dishes and left to germinate, or sprout. Small, root-like structures, called hyphae, then branch out to look for plant roots, such as the carrot or chicory roots that Tzng has placed in the dish with the spores. The roots are essential for a spore’s successful germination.

“Once the spore finds the root, it’s going to puncture the wall and extend into it,” Tzng says. “Then there's a trade-off of nutrients. If there were no roots, the spores could still germinate but after some searching, they’ll start growing these things called secondary spores, which is like repackaging itself. They go back into dormancy and then wait for the next best opportunity.”

As the hyphae continue to grow, Tzng collects her data, measuring both their length and growth rate. As she continues to experiment, she expects to find that the spores with endobacteria grow faster than those without.

Troubles in spores, troubles in roots

The challenges of working with spores in a laboratory setting may contribute to the lack of spore research, according to Tzng. She has not had an easy time obtaining results. For simple structures, spores can be quite difficult to grow and maintain, and Tzng has had to go through several rounds of trial and error.

“I think I've done more troubleshooting than actually experimenting, because these fungi are very finicky! They don’t germinate easily. They're looking for very optimal conditions,” she says.

Tzng has encountered obstacles at almost every step of the way.

“At first, we found out that, basically, all the spores were dead. But we had to figure out if they were dead in the samples that we were receiving, or because of the way I was sterilizing them, or some other factor. That led to changing the way we were sterilizing the spores. We think we might have been shaking them too hard and damaging part of them, so they died before they could germinate,” Tzng says.

Once Tzng devised a better way to sterilize the spores, then she started having trouble with the roots.

“You decide which roots to use based on the species of fungi. My species [of spores] is supposed to be put next to chicory roots, but in the first year the roots were doing really badly. They were brittle, turning strange colors, and were overall very unhealthy,” Tzng explains. “So then we tried carrot roots, but they weren't making the contact needed to form the symbiotic relationship we’re looking for. So that had to be held off until we got new chicory roots.”

Tzng continues to experiment and is working on a review paper that documents her challenges.

Branching forward

“This is a pretty small field,” Tzng says. “Spores are not easy to work with, which I think plays a factor into why they’re often overlooked.” She believes that this difficulty is why researchers haven’t yet discovered more ways that spores could be useful. Once an overlooker of spores herself, Tzng has become convinced of their importance. She hopes that research on the benefits of spores will continue, in both the Pawlowska lab and the broader scientific community.

“There's a lot of gaps in the research, and a lot of effort has to be made so these spores can get more attention. Then the research can be put towards bigger things,” she says.

Tzng is grateful for the challenge that working with spores presented. Through her research, she has learned to troubleshoot. The obstacles she faced forced her to be more creative in her experimentation and even to gain a new perspective on life.

“I was really anxious that things weren't working the way they were supposed to,” Tzng says. “But I learned that it’s important to just keep going forward with a positive mindset. I learned that what I might perceive as failure is more often unexpected success. Failure isn't always just failure; it's how you look at it and learning what your next steps are from that.”

Read this story on the Cornell Research website.