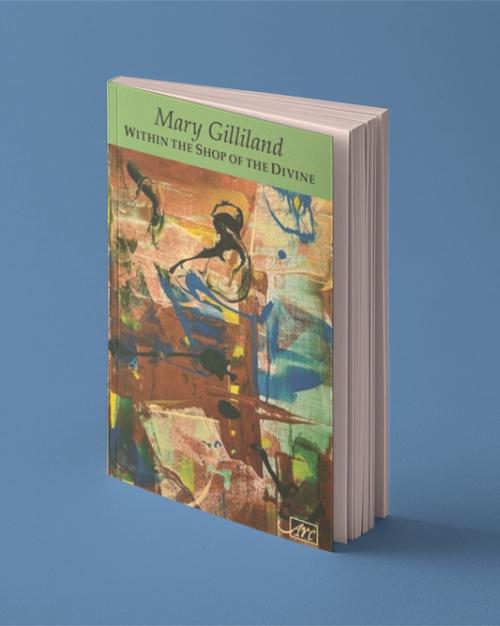

In “Within the Shop of the Divine” a new book of poems by Mary Gilliland, a Saint Anthony statue that glows in the dark lights the way into poems that connect siblings beyond death, that imagine a medieval chapel’s construction and that visit a holy site of pilgrimage off the British coast.

Other poems in the collection consider Satanic bargains, consult astrology and remind us who Frankenstein really was – the scientist whose name “registers/in our roster/the monster.” The natural world – plant life, animals, the sea – is never far off, and many ancient places are revealed.

For Gilliland, senior lecturer emeritus with the John S. Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines, a poem begins with sound, when “an arc of language, a phrase or sentence sonorous or obvious or riddling wants to be written down,” she said. “Part of the art is being found by the words.”

Gilliland said it can take some time for her to realize that another persona is speaking in a poem. In this collection, she channels Cain, Dionysus, “a disgusted chicken packer who decides to leave the factory,” and other unsummoned voices, as well as her own travels, experiences and emotions.

“Within the Shop of the Divine” was published on Oct. 31. The College of Arts and Sciences spoke with Gilliland about the book.

Question: Do any of the poems in this book have remarkable origin stories?

Answer: After a spate of years publishing only in journals, I’ve had six poetry collections published in six years now and remarkable origins are many. Herewith “Rosslyn Chapel’s Artisans”: I stayed at Hawthornden Castle in Midlothian [Scotland] primarily to spend time across the River Esk at Rosslyn Chapel, known for its mysteries. Every inch of the magnificent interior is carved with figures or patterns.

Another fellow and I decided to bushwhack back to the castle. It was early spring, the hills alive with coltsfoot. There was just one complication: our shortcut required traversing an enormous tree that had somehow fallen perfectly as a bridge over the water a hundred meters below. Take the depth of an Ithaca gorge and double it – that’s the Esk ravine. Did I dare? “Well, come on” called my companion, who’d already walked across. Remarkable, my crossing, thanks to a quick decision to put my mind in my feet and turn the thinking off.

Q: Thinking of one of the book’s first images, the Saint Anthony statue that “glows in the dark so I can find him,” would you speak about the importance of everyday objects in these poems?

Soon after that first image you find “our brother’s//ashes.” The final words of the poem recollect siblings playing out our futures – “he said he’d be a statue.” It’s a family poem; my sister is mentioned and our Ithaca community alluded to. That little glow holds the speaker’s grief. Objects are numinous in that they focus our awareness. They invite a closer look.

A poem provides context of fewer words than most genres, thus shrugs off familiarity and re-introduces the usual as noticeable. In one poem, that’s a votive figurine, in another, a sculptor’s chisel, rasp and file. In “Holy Island” it’s maps and the ingredients for paint. How to represent ruins everywhere? “a thin red arch of sandstone thumbed by wind.” How to update Hades and Persephone? Give him a motorcycle, give her an adamant talk-back about his wallet. Sometimes a special object is a wish: “ribbons torn from my unruly hair” embodies something about my character rather than appearance.

Q: Between the “Divine” of the title and the devil’s appearance in many of the poems, what role do spiritual forces and religious traditions play in this collection?

“Subverting received traditions” has been said of my poems, a position that also informed courses I designed while teaching at Cornell. My early spiritual life was framed by Roman Catholicism: its mysteries of joy, sorrow, glory are used like a refrain in “Lit with Radiance.” Did you ever read so deeply you lived it? I fed on classical Greek mythology as a very young child, re-read the stories so often you might say I studied them. “Within the Shop of the Divine” includes Proserpine, Odysseus, Bacchus, Nemesis.

As a teenager, inspired by the poetry of Gary Snyder, I began to practice Buddhism. My Tibetan teacher of Dzogchen stressed the primary practice of presence, attention. He would often say “Everything is symbol.” I hold that true; every appearance in my poems from every tradition is an apparition, a metaphor for a certain potential or kinetic energy that we humans reach for in our quest to become the best or the most evil or the most compassionate.