If your commute involves packed subway cars, chances are your headphones are piping something rather different from your seatmate’s. A new study analysing individuals listening patterns suggests that urban living not only exposes people to a wider array of sounds, but also pulls listeners apart, taste-wise, from those sitting right beside them.

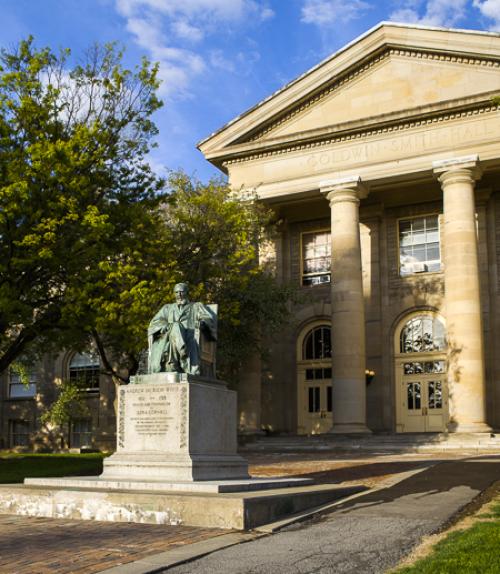

An international team, including scientists from Cornell University, Deezer Research in Paris and Max Planck Institutes in Germany, sifted through 250 million listening logs from 2.5 million users in France, Brazil and Germany and determined that living in a metropolis broadens our musical horizons, and makes our playlists less alike. Their study, “Mechanisms of Cultural Diversity in Urban Populations,” published June 4 in Nature Communications.

The work was done in collaboration with Deezer Research in Paris. Deezer is a global music streaming platform available in 187 countries featuring over 90 million tracks.

“This paper is particularly special as it represents a rare collaboration between academia and industry, giving us access to individual-level interaction data from millions of users. We used this unique dataset to investigate what makes cities culturally diverse,” said co-author Nori Jacoby, assistant professor of psychology in the College of Arts & Sciences and group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics.

The research team measured diversity of music across urban populations in two ways. First, they looked at how similar (or not) the songs played by people in the same area were. Across all three countries, the larger the city, the more distinct people’s musical tastes were from their neighbors. They found there’s less of a single, shared musical taste in big cities.

“A resident of Paris, for instance, shared far fewer tracks with other Parisians than listeners in Orne (a region in northwest France) did with their neighbors,” said Harin Lee, corresponding author and Jacoby’s doctoral student.

The researchers also calculated each individual’s “listening radius” – roughly how far they roamed across genres and artists. They found that people living in larger urban areas also tend to listen to a broader variety of music, expanding their personal musical repertoire.

The study also found that this listening radius changes over the course of life. When the researchers lined up listeners by age they saw a near-perfect bell curve. Musical radius expands rapidly from the mid-teens, reaches its widest span in the late-twenties, and then contracts, slowly but surely, through mid-life and beyond. The team found the exact same inverted-U pattern in France, Germany and Brazil, even after stripping out auto-play tracks and other algorithmic nudges.

According to Lee, the twenties is when people typically leave home and meet new people, as well as having time and interest in exploring. After 30, responsibilities mount, spare hours shrink, and the playlists built during our exploratory years can solidify into habit.

But the study shows that fifty-year-olds still roam far wider than most teenagers. They may have simply begun to circle the artists and eras that resonate most.

To explain the difference in big-city listening habits, the researchers assembled a detailed demographic portrait of each city, covering everything from age, income and immigrant share to average Facebook-friend counts and the number of nearby music venues. Through computational models accounting for all these factors, the team concluded that the demographic mixing in cities contributes to the musical diversity, especially in the very largest cities, but that wasn’t the full story. The researchers speculate that the differences in listening habits could be partly because of a lack of cultural resources in more rural areas.

“Even after controlling for these demographic differences, larger cities still fostered greater musical variety,” Jacoby said. “This suggests there is something about the urban interactions and experience itself is at play.”