This is an episode from the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast's fifth season, "What Do We Know about Inequality?" from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about inequality. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Thursday through the fall semester.

If you were born or raised in the United States, you’re probably familiar with the idea of public education. One of the defining features of American democracy is our compulsory system of tax-payer supported education. It ensures that all children, regardless of race or income, have access to school.

It may surprise you to know, then, that our education system owes everything to the Civil War-era freedoms gained by African Americans, and that the inequalities institutionalized during that period remain with us today.

As early as the 17th century a few northern states had established some semblance of public schools open to the non-wealthy, but compulsory, tax-supported education is a legacy of Reconstruction – the period of southern unification and rebuilding that followed the end of the Civil War. During that period, the federal government provided funds to southern state legislatures to educate all children in the thirteen former slave-holding states.

This education was only possible for Black students because federal troops occupied the region. The troops were there to ensure that the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution were carried out. These guaranteed Blacks freedom from slavery, the right to citizenship, and the right to vote. During Reconstruction, a relatively short period between 1868 and 1877, federal funds paid for these troops and also made possible schools, teachers, and school buildings for southern children, both Black and white.

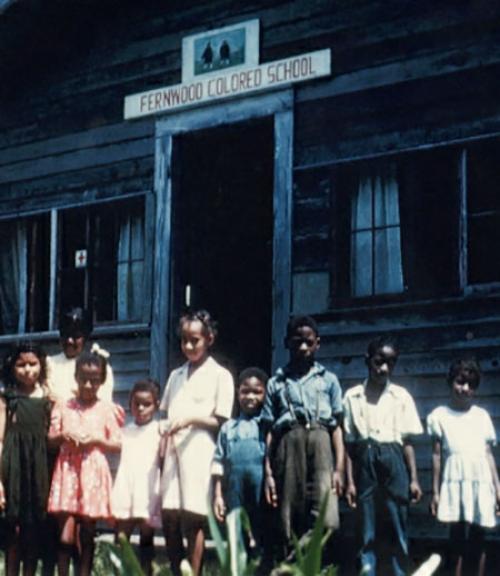

However, when Reconstruction ended and federal troops withdrew, southern legislatures moved aggressively to dismantle the educational progress Black communities had made. All across the former slaveholding south, state and local governments passed laws decreeing that any schools that allowed for an integrated education were in violation of the law. They also instituted policies forbidding the use of "white tax dollars" to educate Black students. Some states went so far as to require Blacks to pay a double tax if they wanted their children educated -- one tax to pay for the education of white children and another to pay to educate their own.

Schools for Black children in the south were a consistent target of economic and social disinvestment. White southern legislatures employed a variety of means to ensure that Black children had as little access to schools and education dollars as they could legally manage. Most southern states allocated less money for the instruction of Black school children and many also shortened school terms for Black children. The average of nine months for white students was reduced to as little as three months for Black students. The legislators’ rationale was that Black children were needed in the fields during harvest time and did not need classroom instruction.

Today, schools that educate the wealthy generally have decent buildings, money for materials, a coherent curriculum, and well-trained teachers. Schools that educate poorer students and those of color too often have decrepit buildings, no funds for quality instructional materials, and little input in the structure or purpose of the curriculum. They make do with the best teachers they can find. As a result of this segregated system that privileges one group over another, graduation rates and educational quality are vastly different depending on the racial and economic makeup of one's community.

Class status, race, American citizenship and tax dollars were at the heart of the founding of public education and remain ensnarled in the debate about public education today. And educational inequality remains an urgent problem. Making public education available to all children within the United States strengthens democracy and it promotes the radical notion of equality amongst all children – be they native born, immigrant and naturalized citizen.

Image: Emanuel C. Hertzler Papers, 1943-1998, Mennonite Church USA Archives