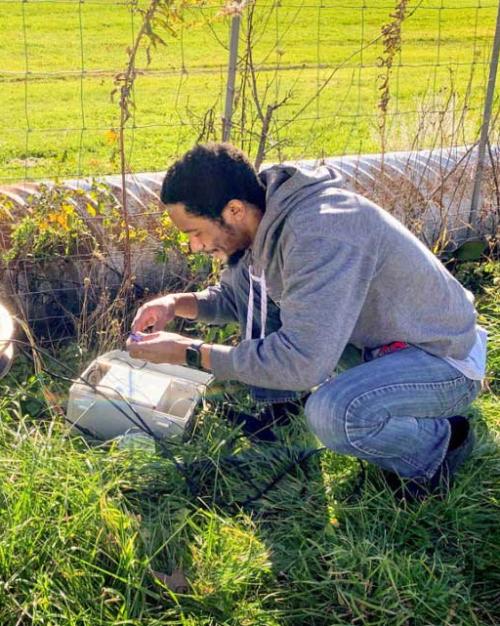

When Gloire Rubambiza was installing a digital agriculture system at the Cornell Orchards and greenhouses, he encountered a variety of problems, including connectivity and compatibility issues, and equipment frozen under snow.

Rubambiza, a doctoral student in the field of computer science, was able to solve these problems thanks to a university that gave him time, funding and institutional support. But he wondered how farmers who lack these resources would tackle the same issues.

He began to study how the research process may be unintentionally creating problems for the farmers, and found that enabling farmers to tinker with their own systems and involving them early in the design process could better translate technology from the lab to the field.

“Despite good intentions, researchers often are not familiar with the diverse, daily challenges of farming or the specific applications their systems will have. We need to acknowledge that gap, so that we can have the intended impact for this technology on rural farms,” Rubambiza said. He is the first author of the paper “Seamless Visions, Seamful Realities: Anticipating Rural Infrastructural Fragility in Early Design of Digital Agriculture,” which he presented May 2 at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Digital agriculture typically involves deploying sensors in fields, collecting data and sending it to the cloud for analysis, then using the results to automate and optimize farm tasks, like irrigation. Small rural farms will likely face many challenges in installing these systems due to gaps in rural infrastructure, such as frequent weather-related power outages and poor Internet coverage.

Empowering farmers to customize their digital agriculture setups will make their systems more resilient to these gaps and help them avoid becoming reliant on “black box” commercial systems, which may lock them into service contracts with companies that could profit from their data against their wishes.

“Historically, people in rural areas have had to create their own infrastructure due to urban-centered technology design and standards,” Rubambiza said.

The researchers also recommend providing farmers with a “cheat sheet” of the problems they encountered during development. This type of troubleshooting is typically left out of scientific publications and presentations, but documenting these hurdles could help farmers deploy and manage their systems.

To bring farmers into the research process, the researchers suggested including them in co-design workshops, recruiting rural youth as research assistants and seeking feedback from extension agents on how these systems could function on real farms.

Some journalists and policymakers have framed digital agriculture as a revolution akin to mechanized farm equipment, or the use of commercial fertilizers and pesticides. Rubambiza hopes that being mindful of unanticipated issues during the design process will allow these systems to be deployed more equitably – so this revolution can have the positive impacts researchers envision.

Co-authors on the study include Phoebe Sengers, associate professor of information science in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science and science and technology studies in the College of Arts and Sciences, and Hakim Weatherspoon, professor of computer science in Cornell Bowers CIS.

Funding for the project comes from the National Science Foundation, the Cornell Institute for Digital Agriculture and Microsoft fellowships.

Patricia Waldron is a science writer for Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.