The first time I met Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’54 was during my clerkship for the late Justice John Paul Stevens in 2000. Although each of the chambers at the Supreme Court operates like a little independent law firm, there is a tradition of Justices inviting clerks from the other chambers for an informal get-together at least once during the term. Justice Ginsburg invited the Stevens clerks to tea in her chambers. Prominently displayed on a wall just outside her office was a framed poster with words from the Parashat Shofetim: “Justice, justice shall you pursue.”

The repetition of the word “Justice” has always been so powerful to me. The passage is taken from a longer description in Deuteronomy of the kinds of judges God wanted the Israelites to appoint – honest judges who would not pervert justice in favor of the wealthy or well-connected, but who would pursue equal justice fearlessly, with particular concern for the marginalized, the poor, the widow, the orphan, the foreigner. Justice Ginsburg’s life and career embodied this rich ideal of justice, first as an advocate for equal rights for women and later as a Justice at the Supreme Court.

Some changes are so profound and rapid that it becomes almost impossible to imagine what life was like before they occurred. Justice Ginsburg began her career in a legal profession that made no room for women. As a law student at Harvard University in the late 1950s, she was one of only nine women in a class of over 500. As the co-founder of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, she helped to usher in the world in which we live, a world where women outnumber men among those graduating from American law schools, and in which women can aspire to anything — including serving on the highest court in the land. Echoing what President Martha E. Pollack says in her own memorial essay in Sunday’s Daily Sun and in the Cornell Chronicle, I, too, perceive the influence of Cornell’s commitment to “any person” in Justice Ginsburg’s fearless decision to enter a legal profession that she then went about transforming.

In the 1970s, as an ACLU lawyer, Justice Ginsburg litigated a series of cases arguing that, as she wrote in her brief in the landmark 1971 case of Reed v. Reed, “[w]hatever differences may exist between the sexes, legislative judgments have frequently been based on inaccurate stereotypes of the capacities and sensibilities of women. . . . [A]ny continuing distinctions should, like race, bear a heavy burden of proof.” That argument — calling for searching and skeptical judicial review of sex classifications — became the law of the land by way of her opinion for the Supreme Court in the 1996 case of United States v. Virginia, the so-called “VMI case.” In that landmark opinion, Justice Ginsburg conceded that — as she put it — “inherent” biological differences between men and women might occasionally justify legal classifications on the basis of sex. But the thrust of her entire career as an advocate — and subsequently as a Justice — was that the universe of such justified cases is far smaller than many had previously assumed. The scope of her impact on how the law regards women — and sex in general — evokes justified comparisons to another transformative advocate who went on to serve as a Supreme Court Justice: Thurgood Marshall.

Justice Ginsburg’s time on the Court also coincided with another seismic shift in our legal culture that we will see play out in the weeks ahead; the polarization that characterizes contemporary political discourse is inseparable from the work of the Supreme Court. That polarization is itself closely connected to the social changes that Justice Ginsburg helped to bring about as an advocate and as a Justice. In the 2016 presidential election, one in five voters identified the Supreme Court as the single most important issue driving their voting decisions. And for most of those voters, issues relating to sex — reproductive rights, LGBTQ rights and the meaning of sex-equality — lie at the heart of their interest in the Court.

Supreme Court nominations used to be boring affairs. At the 1939 confirmation hearing for Justice William O. Douglas, he waited patiently outside the hearing room in case Senate committee members had any questions for him. None did. These days, Supreme Court Justices are — for better and for worse — celebrities. Of course, even among that rarefied group, Justice Ginsburg stands alone. No one else on the Court is known by their initials. No one else has a Saturday Night Live persona. Children don’t dress up for Halloween as Stephen Breyer.

And yet Justice Ginsburg’s 1993 nomination and confirmation also bore traces of the earlier, less partisan era. Her closest friend on the Court was the late Justice Antonin Scalia. She was the last Supreme Court nominee to receive more than 90 Senate votes in her favor. (It is almost impossible to imagine a world in which a nominee ever will again.) So it is sad — but not surprising — that the fight over her replacement has already begun. In his very statement noting her passing, just an hour after her death, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) launched that fight by promising that “President Trump’s nominee will receive a vote on the floor of the United States Senate.” Much of the commentary over the weekend — across the political spectrum — focused on her possible replacement.

One does not need to be a Democrat — or to agree with Justice Ginsburg’s views on every issue — to be inspired by her pioneering example or to lament our apparent inability to celebrate her remarkable life before returning to our toxic judicial politics. Perhaps, here at Cornell, where she excelled as a student and met the love of her life, we can get it right. Today, let’s take a moment simply to remember this inspiring Cornellian. Let’s pause to honor this incredible woman who dedicated herself so fiercely to the values spelled out on that poster I saw framed outside her chambers. Justice, justice.

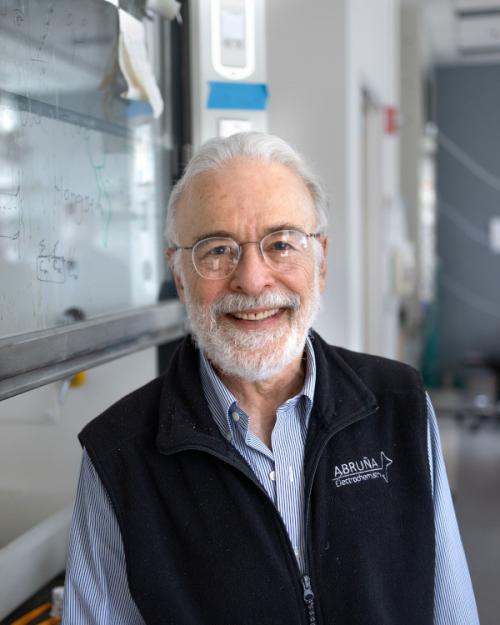

Eduardo M. Peñalver ’94 is the Allan R. Tessler Dean of Cornell Law School.

This article originally appeared in Sunday’s edition of the Cornell Daily Sun.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.