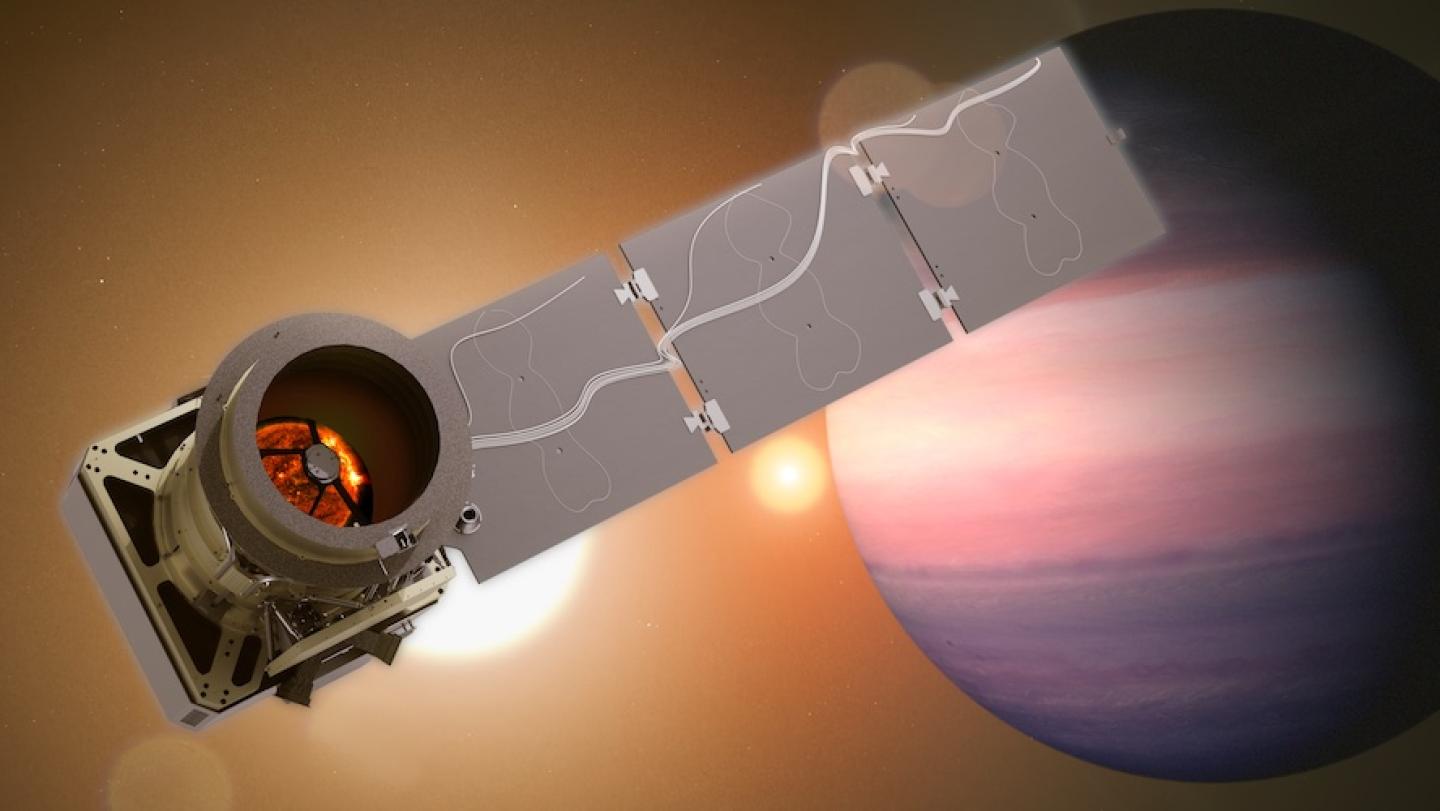

On Jan. 11, the Pandora SmallSat launched atop a SpaceX rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. Tasked with studying exoplanet systems around small stars, the refrigerator-sized satellite will focus long-term attention on 20 systems during its one-year mission.

“The Pandora project will provide us with valuable information that will allow us to gain further insights into small planets orbiting small stars that we’re studying with the James Webb Space Telescope,” said Nikole Lewis, associate professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences and a member of Pandora’s science team.

The Pandora SmallSat includes a 0.45-meter telescope, visible-light photometry and near-infrared spectroscopy. It is the first satellite to launch in NASA’s Astrophysics Pioneers program – small-scale, low-cost missions designed to train early-career scientists in leadership, including Trevor Foote, Ph.D. ’24, a former member of Lewis’s research group.

Work by Lewis and her research group on exoplanet atmospheres helped to instigate the Pandora project. For the past 10 years, she and other researchers have been investigating earth-sized planets orbiting small stars – K and M dwarfs. These systems offer advantages for studying planets as they transit in front of their stars, making them prime targets for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), Lewis said. But they pose challenges, because small stars have lots of flares, hot spots and atmospheric effects that affect signals.

Pandora’s main goal is to focus on each of the 20 exoplanet-host star systems for a long period, Lewis said, to disentangle signals coming from exoplanets from the signals coming from their stars. Each long observation period will capture a star’s light before and during the planet passing in front of its host star.

“Large missions like James Webb don’t have the time like that to dedicate to one system,” said Foote, now a NASA Postdoctoral Fellow at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. “But with a small mission like this, we can stare at a system for a full 24 hours and get a full picture of how the stellar surface behaves before the planet transits in front of the star.”

Foote dedicated much of his doctoral work to this mission, contributing to several Pandora components, including a 2D image simulator, an observation scheduler and development of the data processing pipeline.

“One of the cool things about a small satellite project like Pandora is it’s small enough in team size that you can get your hands on both sides – sciences and engineering,” said Foote, who is interested in exoplanet science and the related engineering problems. “There’s plenty of work to go around and not enough hands.”

Now in orbit, Pandora is going through a 30-day start-up period. Science observations will start in February, with the first users being the core working groups across the United States and Canada, including Cornell, the University of Arizona and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Foote is a mission manager, coordinating three groups: the science operations center at Goddard in Maryland, the mission operations center in Arizona, and the data center at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. He’ll focus on the observation calendar and problem solving.

“And on the side, I’ll be analyzing data and trying to further the field in understanding stellar contamination and how it’s been impacting exoplanet astronomers,” he said.