Rich social and cultural transformations came to the classical world in Late Antiquity, roughly 250 CE to 750 CE. Moving away from the paradigm of decline and fall, historians have taken a new look at the period, including the rise to prominence of Christianity. What was everyday life like for those early Christians? And how did they view their place in the Greco-Roman world?

These are questions Éric Rebillard, Classics and History, seeks to answer from the perspective of a Roman historian. His viewpoint encompasses a new way of asking age-old questions about the early days of Christianity. “For a long time, scholars who worked on early Christianity were Christian believers looking to find answers about the origins of their own religion,” he says. “In the last 20 years, more and more studies on Christianity are done by people like me who define themselves as Roman historians. We are studying the Roman Empire in which Christians happened to be living.”

Staying Socially Involved

In the past, church historians looked for historical evidence that helped to bolster their own beliefs, Rebillard explains—for instance, emphasizing that early Christians separated themselves from larger society. He tackled that idea head-on in his second book, Christians and Their Many Identities in Late Antiquity, North Africa, 200–450 CE (Cornell University Press, 2012). “I developed a framework to understand and to address the fact that Christians were not segregated in life,” he says. “Christians, like anyone else, had many components to their identity, and Christianness was just one of them. It was given salience only in some contexts, intermittently, and not necessarily very consistently.”

“Christians, like anyone else, had many components to their identity, and Christianness was just one of them.”

Rebillard formed his hypothesis by taking a fresh look at the works of ecclesiastical writers who were unhappy that Christians remained embedded in society but who, nonetheless, gave accounts of what was happening. “It’s important to stop looking at Christians as people who withdrew from social life,” he says. “We have many elements which show that was definitely not the case. From our sources, we know that people such as incense dealers and statue makers could be Christians and still do their jobs. They could still be members of an association of statue makers, for example, or of a neighborhood association where not everyone was Christian, and so on. This goes against the prescriptive message of a lot of ancient writers who wanted Christians to only be Christians all of the time.”

Rebillard continued his reassessment of the life of early Christians in his recently finished fourth monograph, The Early Martyr Narratives: Neither Authentic Accounts Nor Forgeries (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020). In it, contrary to the conventional position of church scholars, he argues that the many anonymous versions of early texts recounting the martyrdom of various Christians were living texts, each as legitimate as the next, altered by ancient audiences to fit the needs of the moment. “Once you know they were living texts, the search for an authentic text doesn’t make sense,” he says. “I also argue that ancient audiences were aware that the texts were constructed narrative, but there was no doubt in their minds that the martyrdom itself was true. The rest was just a way of interpreting or celebrating the martyrdom.”

Adding Christian Practices to a Religious Repertoire

Rebillard received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020 to work on a new book—this one about the rise of Christianity. In this work, he intends to examine the suppositions that underpin what many scholars call the triumph of Christianity, wherein they maintain that the religion grew from a few thousand believers at the time of the death of Jesus to millions by the reign of the emperor Constantine at the beginning of the fourth century.

“The growth of Christianity is always presented as something exceptional,” Rebillard says. “I am beginning my research by looking at the issue of the numbers of Christians. None of the numbers people usually use are solidly established. A lot of scholars start by saying, ‘Well, that’s a huge increase of converts. How do we explain it?’ This question is formulated based on a premise that is already disputable.”

Rebillard is also proposing a very different way to think about conversion. “It’s not a radical break where people change their identities and definitively drop all their other religious practices,” he says. “It’s a scenario where people add, on a trial basis, some Christian practices to their religious repertoire.”

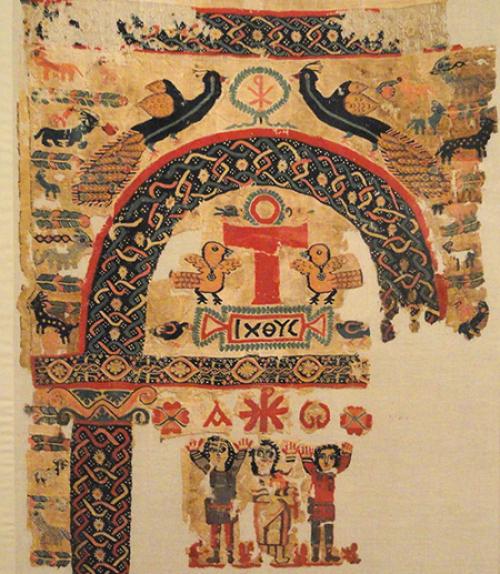

Rather than depending on huge numbers of fervent converts, Rebillard argues, the growth of Christianity actually came from the success of Christian symbols and practices that penetrated throughout society far beyond the actual number of Christians enrolled in the church. He mentions the symbol of the cross as an example. “Starting in the third century, the cross was used on a number of objects,” he explains. “Historians usually think if they find these objects, it means the people living there were Christians, but we don’t have any solid evidence of that. We do know from some of the texts of the time that people were using the cross on amulets without necessarily being Christians. They would carry a Christian symbol one day, while on another day they might carry a symbol of the goddess Isis or some other deity.”

Defining Christian beliefs in this time period is also difficult, Rebillard says, as there were many different groups claiming to be Christian. “They were not all unified or even thinking the same thing,” he says. “They followed a great variety of beliefs and practices, and even by the time of Constantine, when there was a majority group of Christians, there were still many minority groups.”

Life of Augustine Leads to Research Path

Rebillard’s interest in studying religion and religious practices in the Roman Empire was piqued early in his research career when he happened to read The Life of Augustine by Peter Brown. Augustine of Hippo was an early Christian who applied Platonic philosophy to Christian teachings and laid the foundation of Christian theology. “I was fascinated by how someone could decide to deliberately renounce rational thinking in favor of belief,” Rebillard says. “I wondered how we can put this in context, how we can understand it without rejecting either one or the other.”

“I don’t work directly on this question now,” he continues, “but it drew me to my research path, along with the idea that religion is part and parcel of the rest of social life and shouldn’t be studied in isolation.”.