The “butterfly effect” was in full bloom on March 14-15 as campus and community members celebrated the environmental and literary legacies of former Cornell professor Vladimir Nabokov.

The celebrations began with a packed crowd listening to a March 14 talk celebrating the opening of Cornell University Library’s “From Nabokov’s Net” exhibit in Mann Library. Events continued on March 15 with a panel discussion entitled “The Butterfly Effect,” and other activities, all part of the “Nabokov, Naturally” Arts Unplugged event from the College of Arts & Sciences.

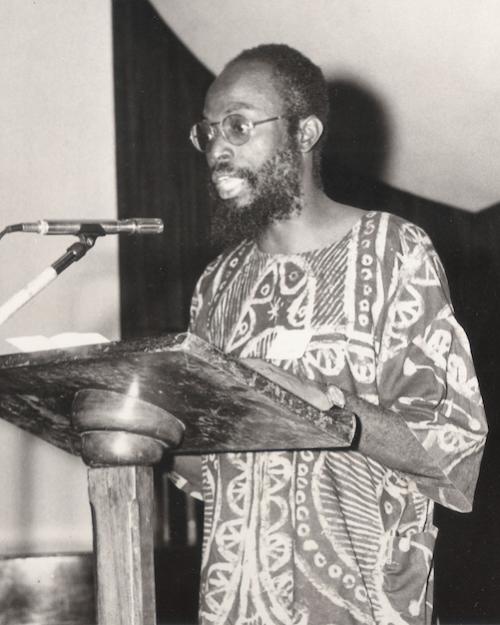

“Nabokov's living legacy crosses traditional disciplinary and administrative boundaries,” said Anindita Banerjee, associate professor of comparative literature (A&S) and mastermind behind the A&S events, who taught a fall class focused on Nabokov’s dual interests in the natural world —especially butterflies — and writing. “Our panelists and participants are engaging in a similar exercise to the one I told my students about last fall. We are going outside of our comfort zones to create something beautiful by taking risks together, not alone. This is absolutely necessary at this time when everything in the universe is telling us to stay in one place, and we are afraid to break out of our boxes.”

Indeed, the Friday events were a collaboration between A&S, the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS), Cornell University Library and its Rare and Manuscript Collection, the Cornell University Insect Collection and the Environment & Sustainability Program, which is a joint program of A&S and CALS.

An avid lepidopterist since childhood, Nabokov, who taught literature and Russian literature at Cornell from 1948 to 1959, was known to spend most of his free time on campus in the Cornell University Insect Collection and his summers out west hunting butterflies with his wife, Vera.

Before coming to Cornell, Nabokov held the post of lepidoptera curator in Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. During the March 14 opening event for the Mann Library exhibit, Naomi Pierce, a biology professor at Harvard who now holds the same curatorial position as Nabokov, spoke of Nabokov’s 1940s research into the evolution and migration of a group of butterflies known as Polyommatus blues. More than six decades later, his theories were confirmed using DNA sequencing techniques.

“He was a master at morphometrics (studying different wing characteristics and types), well before his time,” Pierce said. “It seems like every time you turn around at the museum, you run into things he left behind.”

The Mann Library exhibit was also a highlight of Friday’s event, where visitors could also wander through the CALS Zone at Mann Library and visit with students showing their projects from the fall class, view a film created by eCornell for the event, and create their own butterfly using traditional and non-traditional materials, with the help of entomologist/artist/Cornell doctoral student Annika Salzberg.

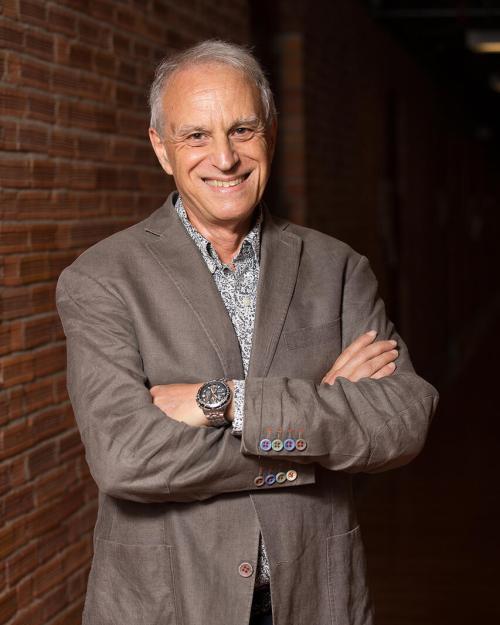

“The Butterfly Effect” panel featured Banerjee; Corrie Moreau, Martha N. & John C. Moser Professor of Arthropod Biosystematics and Biodiversity and director and curator of the Cornell University Insect Collection (CALS); Jose Manuel Prieto, novelist and associate professor of Spanish, Seton Hall University; Katherine Reagan, curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Cornell Libraries; Jenny Leijonhufvud, exhibits curator, Albert R. Mann Library; Anurag Agrawal, James A. Perkins Professor of Environmental Studies, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (CALS) and Jenifer Presto, associate professor of Comparative Literature, University of Oregon. The panel was recorded and can be viewed here.

Reagan explained that shortly after she arrived at Cornell in 1998, she was tasked with creating an exhibit to celebrate Nabokov’s centenary. Since that time, she’s added many Nabokov items to the university’s collection, particularly first editions of his works and books where he’s hand-written dedications or annotations,

“As soon as he received a copy of a newly published work fresh from the press, the first thing he did was to promptly sit down and read it closely, with great attention, line by line,” she said, adding that he made notes about every correction on the fly leaves of each book. “The same attention to detail that informed the distinctions he was able to make between subspecies of butterflies is borne out here.”

Other items in the Cornell collection include notes between Nabokov and publishers and colleagues and even Nabokov’s account books, which include meticulous records of his paychecks, as well as expenses for everything from cigarettes to ice cream.

“But amongst all the calculations and arithmetic are butterflies; everywhere, always butterflies. There are butterflies on page after page of these account books, on the backs of letters and envelopes, butterflies flitting across his pages of lecture notes and colorful and fanciful butterflies to honor his wife,” Reagan said.

Leijonhufvud, the Mann curator, detailed her own meticulous reading as she planned the exhibit, including an early article Nabokov wrote about discovering the Lysandra cormion, which he described as a new species of European butterfly in 1941.

“He was in the French maritime Alps in 1938 and caught two unusual male butterflies,” she said. “He thought this might be a new species, but he didn’t have time to collect anymore or to find any females. Two years later, he and his family fled on the last boat out of France as the Nazis were invading. But he brought them with him, these two special specimens.”

Presto read Nabokov’s poem “Lines Written in Oregon,” which Nabokov published in The New Yorker in 1953 during a summer spent dividing his time between butterfly hunting and writing his most famous novel “Lolita.”

“I was immediately struck, not only by how it captures the landscape of the Northwest, with its endless shade of green, but also by how it provides a poetic counterpoint to Lolita, with whose composition it is intimately bound,” Presto said.

Exploring other references to nature within Nabokov’s work, Presto said Nabokov is “much more than a writer of world literature, with its indebtedness to translation, circulation, reframing and adaptation. He is also a practitioner of a special form of niche literature: one that is closely attuned to the natural world… and the ever so important niche relationships that [Joseph] Grinnell wrote about in 1917. Perhaps, just perhaps, in our era of climate change and habitat loss, and of widespread claims, even within the Academy, of the increasing irrelevance of the humanities, this is exactly the type of writing we need.”

Banerjee plans to continue her work on Nabokov, teaching this class again next spring and planning future events and projects.

“My thinking about this project came from the fact that here I was at Cornell and Nabokov was kind of everywhere, but also nowhere,” she said. “I began to feel the absence and began to feel the need for us to engage Nabokov in material, concrete and living ways. The only way to do that seemed to be to run from our building in Goldman Smith Hall in the Arts Squad to Comstock Hall, and back and forth, and back and forth, and to break the boxes that we all live in.”