Hundreds of students, faculty and community members braved a foggy, rainy night Dec. 2 for a behind-the-scenes look at the New Horizons mission to Pluto, given by mission scientists Cathy Olkin and Ann Harch in the Schwartz Auditorium in Rockefeller Hall.

“New Horizons represents a particular milestone because it is the completion of mankind’s initial exploration of the solar system,” said Phil Nicholson, professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences, in his introduction. “This is the last of the classically considered planets to be visited by spacecraft.”

It took 50 years for this achievement – and it took New Horizons itself almost 10 years to cover the 4.67 billion miles to Pluto.

Jason Hofgartner, Ph.D. ’15, who will join the New Horizons mission team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, in January as a postdoc, recalled his excitement when he saw the first high-resolution image.

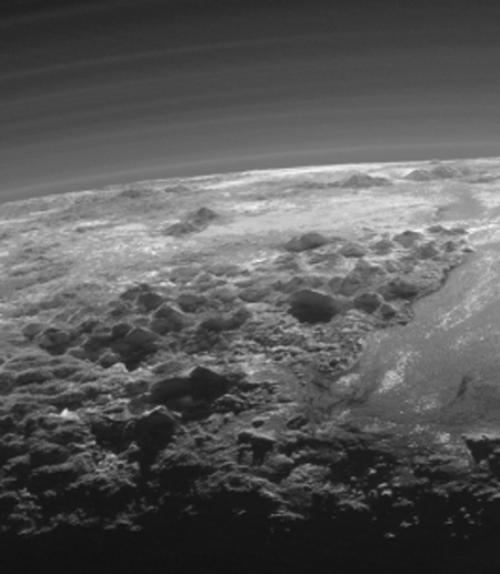

Even as it was being processed and beginning to appear at the top of the screen, “we could see significant topography in the image,” he said. “Everyone rushed to their desks to calculate the height of the mountains. But we didn’t expect they’d be several kilometers high. It was an incredible experience to be among the first people to see these ice mountains.”

Olkin, deputy project scientist, showed the best previous photo scientists had of Pluto – a blurred blob of light. The contrast with the New Horizons photos she shared was so startling that the audience broke into applause.

Harch, lead sequencer of the science instruments on the spacecraft, described the difficult challenge of targeting with the spacecraft and scheduling the sequence of actions it would take during its brief flyby.

“This is the fastest object ever to leave Earth’s orbit, launched at 36,000 miles per hour. It passed the Moon in nine hours,” she said.

Its speed is so great, she added, that it has escape velocity from the solar system and it will keep going. Its nuclear power source – just enough to run two lightbulbs on earth – will be sufficient to continue operating the spacecraft until around 2040, if NASA approves further investigations.

Without any moving platforms, the only way to point the instruments is to move the entire spacecraft; Harch said she and the sequencing team had to craft 10,000 commands for the nine-day flyby: “That’s why it took 10 years to plan.”

The mission team chose an area to aim their cameras where there was an interesting mix of ices, said Olkin – which turned out to include the heart-shaped region that has become so famous. Part of the region is a large glacier made of exotic ices: methane, carbon monoxide and nitrogen, all gases found on Earth.

Olkin gave a visual tour of her favorite sites on Pluto, which include what may be ice volcanoes, called cryovolcanoes, and impact craters at the edges of the glacial region. These surprised scientists by containing ice at their bottoms, which may indicate that the glacier has flowed recently.

“It was pretty exciting to find mountains, about as high as the Rockies,” Olkin said. “They’re probably made out of water ice because other kinds of ice would relax after a while and not keep the sharp crests that we see in the images.”

The moons of Pluto, too, offered many surprises. Olkin said she’d expected Charon to be cratered like Earth’s moon, but it proved much more interesting, with deep canyons extending almost all the way around, mountains surrounded by sunken terrain, and a large area at the north pole the mission scientists have nicknamed “Mordor Macula.”

But, said Olkin, only 25 percent of the data from New Horizons has been received so far. It will take until October of next year to replay all the data.

“This is science in action,” she said.

This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.