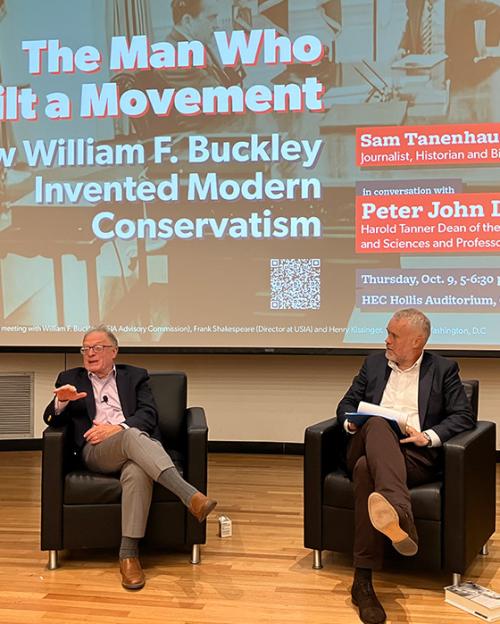

When Sam Tanenhaus wrote to William F. Buckley in 1990 to ask the conservative icon for an interview, Buckley was “about as famous a public figure as you could be in America,” Tanenhaus said during “The Man Who Built a Movement: How William F. Buckley Invented Modern Conservativism,” an event hosted Oct. 9 by the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S).

“He was on television every week, he edited this famous magazine, he was a bestselling novelist and memoirist. He was a huge celebrity. And I was nobody from nowhere.”

Yet Buckley invited Tanenhaus – just starting out as a writer at the time – to his home and into a years-long correspondence, eventually choosing him to write his biography. Tanenhaus published “Buckley: The Life and the Revolution that Changed America” this year after decades of research, and he shared stories about his quest to shape this “big American story about a big American life” during his conversation with Peter John Loewen, the Harold Tanner Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Tanenhaus, now the author of several books with top newspaper credentials as former editor-in-chief of both the New York Times’ Book Review and the Week in Review and a Times writer at large, visited Cornell Oct. 6-10 as the fall Zubrow Distinguished Visiting Journalist in A&S. He met with students and faculty, attended classes and taught a masterclass on op-eds and narrative writing. He told stories every step of the way and reminded his listeners – many of them accomplished or aspiring writers themselves – that politically complex and even morally ambiguous material makes for great storytelling.

“Buckley” is “a long-awaited book, well worth the wait,” Loewen said in his introductory comments.

William F. Buckley was “fun to write about, but hard to get to know,” Tanenhaus said. Besides being a much-interviewed media figure who’d heard all the questions before, Buckley was a complicated person with many contradictions and even some secrets Tanenhaus would not discover until after his subject’s death in 2008.

In a wide-ranging conversation, Tanenhaus and Loewen discussed the mid- and late-20th century conservative revolution sparked by Buckley. They talked about his upbringing in a Catholic, conservative and culturally Southern family that had secrets of its own. For instance, the family owned a segregationist newspaper in South Carolina, which no one in New York, where Buckley and some of his many siblings were active in politics, knew about, Tanenhaus said.

Above all, Buckley’s legacy will be in conservative media, Tanenhaus said. The National Review, which Buckley started in 1955 but formulated much earlier, paved the way for conservative media outlets including Fox News and, more recently, Bari Weiss’ online outlet The Free Press, even as it launched writers like Joan Didion and Garry Wills who would later break ideologically from Buckley.

“Buckley was the first to see that political debates are cultural debates,” Tanenhaus said.

Sifting through material for the book, Tanenhaus said he was searching not just for information, but for a story.

“Reciting the facts of somebody’s life doesn’t make much of a narrative,” he said. “I had to find what I thought the threads of the story were.”

As a biographer, he said, he can’t answer all the questions or reconcile all the contradictions. Instead, he tries to give the most accurate account and let the reader figure out who the person is – but guided by Tanenhaus’ chosen narrative arc. Given the material he had to work with, Tanenhaus shaped “Buckley” into what he called a moral drama, inspired less by the idea of a cradle-to-grave linear biography as by the epic fiction of novelists like Leo Tolstoy.

Throughout the week, Tanenhaus recounted his experiences from his work at legacy publications and insight into the evolving media landscape.

“Reporting is the aspect of journalism most important now and least represented in the expanding media environment,” he told students, faculty and community members in his masterclass on narrative writing. “Think about how you can convert the knowledge and expertise you have into information people outside your professional community can grasp and use.”

Although newspaper writing is competitive today (“turf battles on a shrinking field,” he called it), he said that the classic 700-word opinion piece has staying power.

Long-form narrative journalism found in the New Yorker, The Atlantic, Esquire and other publications is going strong, he said, calling it “essentially an American invention.”

For a writer, there is no better material to work with than complicated histories and personalities, such as those of William F. Buckley, Tanenhaus said. People ask him how he could keep writing about Buckley once he learned the details about what he did and believed.

“I tell them – and this is, I guess, the ruthlessness of the writer,” Tanenhaus said, “I just think it makes a better story.”

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.