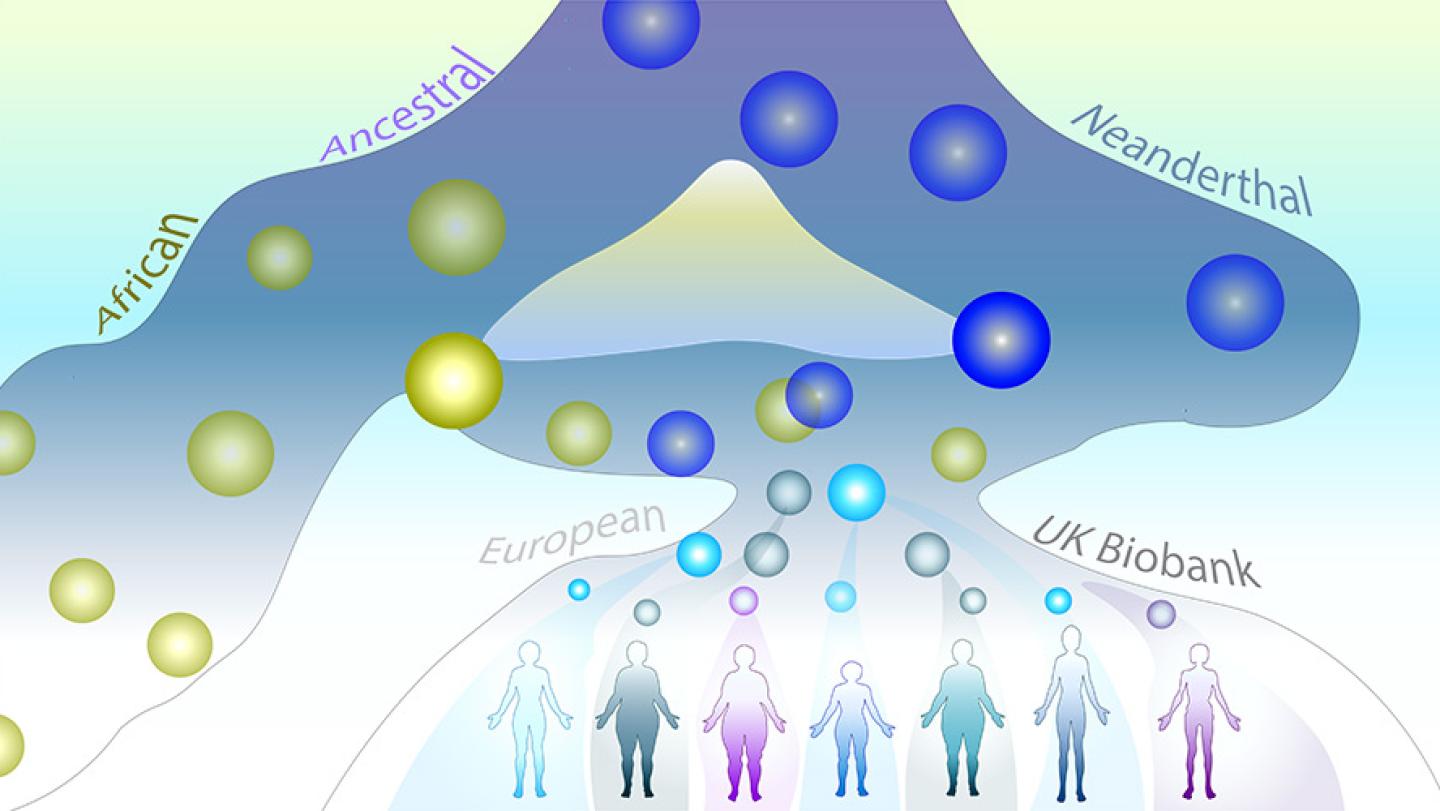

Recent scientific discoveries have shown that Neanderthal genes comprise some 1 to 4% of the genome of present-day humans whose ancestors migrated out of Africa, but the question remained open on how much those genes are still actively influencing human traits — until now.

A multi-institution research team including Cornell has developed a new suite of computational genetic tools to address the genetic effects of interbreeding between humans of non-African ancestry and Neanderthals that took place some 50,000 years ago. (The study applies only to descendants of those who migrated from Africa before Neanderthals died out, and in particular, those of European ancestry.)

In a study published in eLife, the researchers reported that some Neanderthal genes are responsible for certain traits in modern humans, including several with a significant influence on the immune system. Overall, however, the study shows that modern human genes are winning out over successive generations.

“Interestingly, we found that several of the identified genes involved in modern human immune, metabolic and developmental systems might have influenced human evolution after the ancestors’ migration out of Africa,” said study co-lead author April (Xinzhu) Wei, an assistant professor of computational biology in the College of Arts and Sciences. “We have made our custom software available for free download and use by anyone interested in further research.”

Using a vast dataset from the UK Biobank consisting of genetic and trait information of nearly 300,000 Brits of non-African ancestry, the researchers analyzed more than 235,000 genetic variants likely to have originated from Neanderthals. They found that 4,303 of those differences in DNA are playing a substantial role in modern humans and influencing 47 distinct genetic traits, such as how fast someone can burn calories or a person’s natural immune resistance to certain diseases.

Unlike previous studies that could not fully exclude genes from modern human variants, the new study leveraged more precise statistical methods to focus on the variants attributable to Neanderthal genes.

While the study used a dataset of almost exclusively white individuals living in the United Kingdom, the new computational methods developed by the team could offer a path forward in gleaning evolutionary insights from other large databases to delve deeper into archaic humans’ genetic influences on modern humans.

“For scientists studying human evolution interested in understanding how interbreeding with archaic humans tens of thousands of years ago still shapes the biology of many present-day humans, this study can fill in some of those blanks,” said senior investigator Sriram Sankararaman, an associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. “More broadly, our findings can also provide new insights for evolutionary biologists looking at how the echoes of these types of events may have both beneficial and detrimental consequences.”

The other co-lead author on the study is Christopher Robles, postdoctoral researcher at UCLA. Additional authors are UCLA doctoral student Ali Pazokitoroudi; Andrea Ganna of Massachusetts General Hospital and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; Alexander Gusev and Arun Durvasula of Harvard Medical School; Steven Gazal of USC; Po-Ru Loh of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; and David Reich of Harvard University.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, with additional funding from an Alfred P Sloan Research Fellowship and a gift from the Okawa Foundation. Other authors received funding support from the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group, the John Templeton Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the Next Generation Fund at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.