As a 19-year-old college student, economist Neil Cholli spent a summer teaching with The Algebra Project in an underprivileged neighborhood of Miami. He’d witnessed “visceral” poverty on trips to India to visit family, “but seeing that kind of poverty and inequality in the U.S., in my own country, was eye opening for me,” he said. “I thought, ‘I have to do something about this.’”

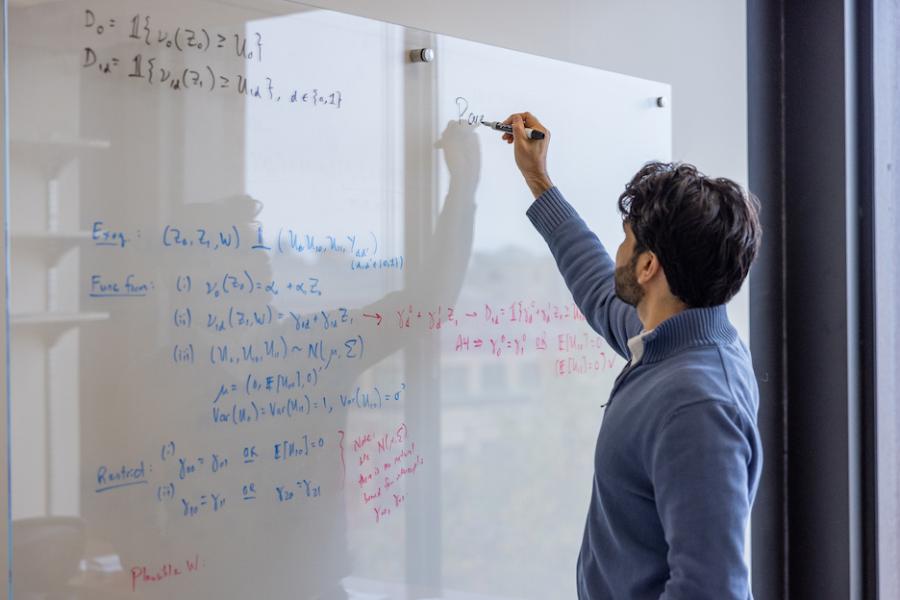

The experience directed his educational path toward economics and set his social mission: to understand the mechanisms of social mobility and to help people transcend generational poverty. As a Klarman Postdoctoral Fellow in economics in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S), Cholli is doing research in labor and public economics, with a focus on applied econometrics. He wants to use that knowledge to be a part of shaping social policy in the U.S.

Children’s futures are influenced by their parents’ circumstances, as well as their larger environment, Cholli said: “Inequalities that exist in the parent generation are transferred to the child generation, perpetuating cycles of poverty.”

Many policies are targeted at parents but end up shaping the environments children are brought up in and therefore shape the child’s outcomes in the future, he said. How can we target interventions at different points within this intergenerational process?

In his highly original research, Cholli is challenging recent influential studies on economic mobility, said Lawrence Blume, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in Economics and Cholli's faculty host. "He's also developing tools to answer the questions we haven't in the past been able to answer, largely due to data limitations."

Cholli is building a body of data-driven analysis. In the doctoral dissertation he wrote at the University of Chicago, which won the APPAM Dissertation Award as well as being a runner-up for the NTA Dissertation Award, he studied the long-term consequences of 1990s welfare-to-work reforms in Denmark.

“You could call it ‘workfare,’ because it was more like job training or vocational training than having to find a job on their own,” Cholli said.

With a rich data set – administrative records of the entire population of Denmark between 1980 and 2018 – he was able to track anonymized individuals year by year and link them with their parents and children, with access to data about their neighborhoods, income, welfare participation, crime, health and education.

Cholli found that Denmark’s added work requirement affected people quite differently depending on what stage of life they were in.

For older adults who may have already been accustomed to cash welfare, the new work requirement was a “complete surprise,” Cholli said. They hadn’t been able to anticipate the change and they’d already passed the time in life when they could invest in their skills through school or work, with the result that the welfare-to-work reform made no positive difference.

Some young adults found the new work requirements so onerous that they dropped out and turned to alternative ways of getting by – including crime.

Children who reached the eligibility age of 18 after the work requirements were in place had the best outcomes, because many of them found ways to avoid the welfare program and its onerous work requirements altogether.

“The story I discovered is a dynamic screening story. Those who are younger, who have more opportunities early in life to pursue education and attach to the labor market, are the ones who screen themselves out from having to participate in welfare programs that have a work requirement,” Cholli said. “So it might not really be the role of work requirements per se, of actually participating in them and gaining skills through them. It may be more that the incentives created by the work requirements themselves generate different types of behavior to avoid them.”

During his Klarman Fellowship, Cholli plans to explore a two-generation approach that invests in simultaneous interventions for parents and children: both job training and high-quality daycare.

Cholli said he learned the power of education for upward mobility from his family.

“Both my parents are originally from India,” he said. “Everything was stacked against my father, but he was able to persevere and get a full-ride scholarship to come to the U.S. for graduate school, even with no money in his pocket. He really is the paragon of the American dream.”

His mother’s father also transcended humble beginnings in an underprivileged village to become a prominent lawyer in India.

“That background and my upbringing motivated me to get the highest education possible,” Cholli said. “And a real recognition of my privilege. I wouldn’t be where I am without my father and mother and grandparents. I recognize that and I feel it’s my mission and duty to do research that is socially impactful, that can help create opportunities for those who are disadvantaged.”

Cornell has a vibrant community working on these research interests, he said.

As a Klarman Fellow, he’s connected to the Department of Economics (A&S) and also the Brooks School of Public Policy. He recently became an affiliate of the Center for Study of Inequality (A&S).