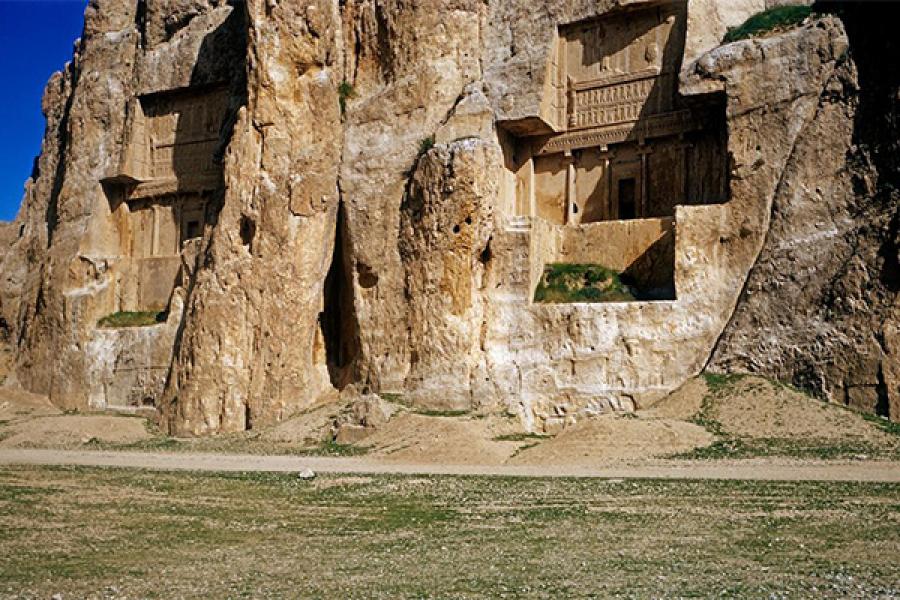

Photograph by Lloyd Llewellyn Jones, https://persianthings.wordpress.com/2013/02/02/184/darius_tomb/

We go way back, this rock relief and I. At this point, it’s difficult for me to imagine what it must be like to encounter it for the first time, unencumbered by a decade of study, reflection, and silent conversation with the reticent rock. Perhaps to you, the sculpture looks like just one more entry in the venerable canon of interesting but obscure ancient art. I probably would have seen it in much the same way, if not for that fateful semester in graduate school, when a professor first awakened me to the sublime pleasure of studying the archaeology of ancient Persia. Now, in my mind’s eye I can only see the monument suspended in a web of thoughts that ricochet against the living rock, testing the limits of what it has to say about humanity and our enduring commitment to an improbable approach to political association that we have come to call empire.

The stone relief that you see was carved roughly two thousand five hundred years ago at a place called Naqsh-i Rustam, a cliff on the Marvdasht plain of southwestern Iran, not far from the well-known city of Persepolis. It is part of the façade of a rock-cut tomb belonging to the Persian king Darius I—a charismatic monarch, conqueror, builder of cities, and ruler of what is often called the first “world empire”. As the mastermind behind this and other projects that suggest a studied philosophy of power, Darius can also be regarded, as I hope to convince you, as a non-Western, pre-Enlightenment political theorist who gave careful thought to the nature of legitimate sovereignty.

There he stands, prominently depicted on a three-stepped podium placed before a burning fire altar. Above him hovers a figure in a winged disk, Ahuramazda, the patron deity of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. God and king interact in a hand gesture of greeting. Below, thirty figures arranged in two registers hold aloft a platform with vertical struts, their arms upraised in a pose that recalls the primordial titan Atlas, who was eternally condemned to hold up the celestial sphere. But unlike Atlas, these figures are mortals. Each man conscripted into the metaphorical hoist of the king is, we know from the accompanying texts, a personification of one of the subjugated peoples of the empire. The relief represents a harmonious, participatory, reciprocal imperial order, and a carefully conceived hierarchical relationship between king and subject. So foundational, so compelling was this succinct graphic treatise on Achaemenid imperial sovereignty that subsequent kings faithfully reproduced it on their own tombs and on other monuments, in slight variation.

Photograph by Machteld Johanna Mellink, Artstor (Bryn Mawr College (MJM-004789))

Armed with this information, no doubt a cloud of associations has begun to take shape in your mind. Lurking in that thought suspension is perhaps some sense of surety about the distinction between “us moderns” and “them ancients”. Or perhaps the word ideology has come to mind, and the tried-and-true means by which imperialists across time and space have packaged subjugation as a glorious divine promise. You may also find yourself vaguely aware of a feeling of distance, of interpretive paralysis borne of unfamiliarity with the esoterica of the east. Or let’s be honest, maybe you’ve gotten no further than the last time you saw Zack Snyder’s 300, or Oliver Stone’s Alexander, or any other pop culture offering that looks to ancient Greece and Persia to rehash old tropes of the clash of civilizations (I watch too, but get to call it research). Let’s set these associations aside.

Over time, I have come to think that what makes the monument at Naqsh-i Rustam so exquisitely provocative is that it simply cannot be reduced to an historical source. The sculptural relief makes conceptual claims. It offers abstract propositions on such things as the paradoxes of empire, the relationship of individual to polity, the tensions of difference and assimilation, and the inclusions and exclusions of a body politic. It is, in other words, a forgotten installment in the corpus of political theory, long dominated by Western thinkers. Like any theoretical production, the claims are formulated out of the historical conjuncture for which they were intended. But they are no less discernable as contemplations on power and society. Accepting this, we can be attuned to the monument’s exceptional resonance with major themes in contemporary social and political thought.

Darius advanced a notion of imperial sovereignty as co-constituted, through the mediation of the sovereign, by that which is a priori (the rights and obligations conferred by Ahuramazda) and a posteriori (the profane realm of imperial subjection), by both predestination and practical action. Modern social theorists will discern in the scene an anticipation of the classic debates over structure and agency. On the one hand, the relief quietly recognizes a dependency of an imperial order on the embodied work of a body politic. The figures engaged in upholding the realm retain the capacity to exercise political choices: “The man who cooperates,” the inscription on Darius’s tomb reads, “him according to his cooperative action, him thus do I reward.” This emphasis on purposeful action introduces unspoken into these scenes the looming metaphorical possibility that the figures could drop their arms, that human agency could entail letting go of the imperial apparatus. On the other hand, an individual’s capacity for practical action is constrained. Subject peoples are literally contained, scripted, and sentenced by the structure whose figurative weight they bear. The platforms in these tableaus are no mere props or incidental paraphernalia, but are instead the very scaffolding that disciplines the conquered and delimits the inside from the outside. Darius also postulated, as modern students of colonialism would agree, that imperialism requires a grammar of difference—a classificatory scheme that is created precisely in order to be dissolved. The differences of dress that distinguish the various subject peoples are undermined by an eschatological promise (too complex to elaborate here) of an eventual return to a state of cosmic perfection, where such earthly differences will have no place.

This monument has been transformative in my formation as a humanist. It provided an unlikely point of entry into the study of colonialism and power. And it led me eventually to advance the seemingly heretical position—based now on a larger corpus of archaeological and written evidence—that we can look to ancient Persia and its neighbors as an untapped wellspring for reflection on problems of empire that extend well beyond the Near East and the ancient world. Looking out from the rock cliff at Naqsh-i Rustam, it has become possible to stake out my own vantage on the humanities from which to question, celebrate, and transform.