After cruising for 205 days over 301 million miles, NASA’s InSight spacecraft – a mission designed to probe beneath the surface of Mars – landed flawlessly Nov. 26 at Elysium Planitia.

Cornell’s Don Banfield felt earthly relief.

Banfield, principal research scientist at Cornell and a co-investigator on InSight’s science team, waited patiently at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory(JPL) in Pasadena, California, listening to mission control with other scientists. They heard when the craft entered the Martian atmosphere, when the parachute opened, the radar locked on, and plunged to 600 meters above the surface, then 300 meters – then silence.

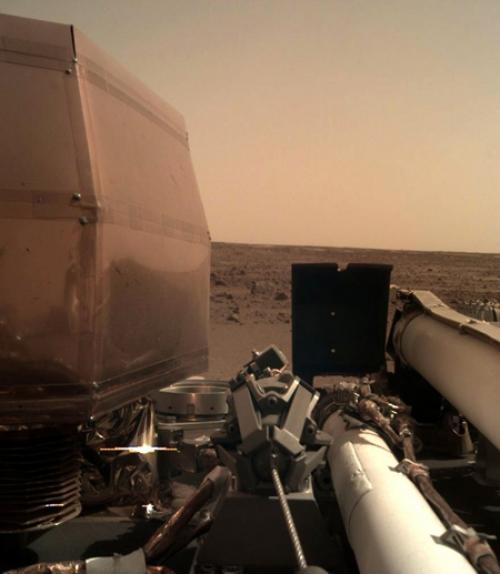

The instrument deployment camera took this image of the Martian surface.

“There was the last second where you mentally extrapolated that it should be on the ground now – but they’re not saying anything. Nobody said anything for four or five seconds,” said Banfield, who said mission control was waiting for a relay signal.

“It was almost hard to believe this wasn’t written by some Hollywood writer to put the perfect amount of delay in there – so that everybody sat on the edge of their seat. Did it actually make it or not?” Banfield asked. “It did.”

“Everybody was ridiculously happy, relieved and it took a while to sink in,” he said. When the first photograph arrived from the Martian surface, Banfield said the mission felt real. “It really drove it home that this is what our new landing space on Mars looks like.”

The InSight lander’s two-year mission will study the deep interior of Mars to learn how celestial bodies with rocky surfaces – including Earth and the moon – formed, according to the mission’s lead institution, JPL.

Hours after landing, InSight sent signals to Earth indicating that its solar panels are open, soaking up enough rays on the red planet’s surface to recharge its batteries after the long trip.

InSight’s twin solar arrays are each 7 feet wide, according to JPL. With the panels open, the lander is about the size of a 1960s convertible. On a clear day, the panels provide 600 to 700 watts – enough power to run a kitchen blender and conduct science.

In addition to his duties as co-investigator on the mission’s science team, Banfield is serving as the lead on the atmospheric pressure sensor instrument group and co-chair of the atmospheric working group. Throughout the mission, he will also monitor wind and temperature data on the Martian surface.

InSight’s pressure sensor will monitor atmospheric conditions and detect dust devils – whirling blasts of wind on the planet’s surface – from much farther away than in previous missions. “Dust devils on Mars, when those go by even from several hundred meters away from the lander, we should be able to see the pressure perturbation from that,” said Banfield. “We will be able to take a census of the dust devils and better understand their behavior and what they can then teach us about the Mars atmosphere in general.”

After landing, the scientists and engineers got to work. Banfield will meet with mission engineers at JPL, in his role as one of the rotating chairs of the science operations working group, to pore over the mission’s operation plans.

“I’m embedded in meetings pretty much all day, as we go over the technical details,” said Banfield. “We’re going to put the instruments on the ground, start taking data and figure out what we’re going to learn about Mars.”

This story also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.