“Buffalo,” said Jonathan Tenney eight times in a row to the crowded room in White Hall. The participants in the Near Eastern Studies (NES) monthly undergraduate lunch laughed as he told them the ancient Sumerians would have had no trouble understanding the sentence.

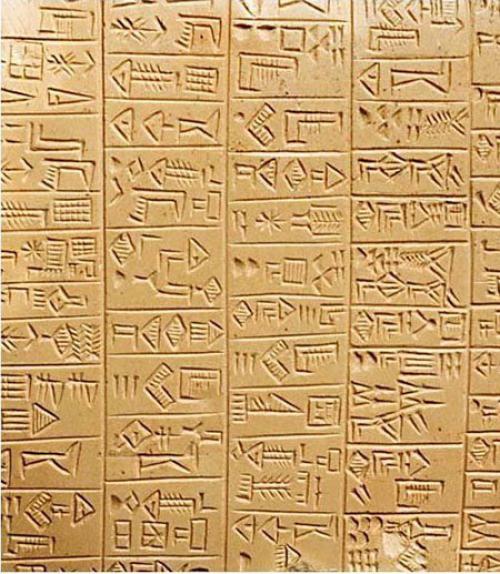

The eight-buffalo sentence, though grammatically correct in English, is difficult to interpret, said Tenney, assistant professor of NES. “What took writing from a simple expression of numbers and things was the invention of grammatical elements like prepositions that enabled literature to be created.”

Students helped themselves to pizza – regular and vegan – salad and soda as they listened to Tenney draw parallels between Sumerian and modern-day communications. The informal discussion ranged from logograms -- where one picture represents something, whether noun or a verb -- to homophony, where one sound can explain multiple things, such as “buffalo” serving as both noun and verb. Tenney noted that in Sumerian, a single picture could be used to mean both “a foot” and “to run.”

Sumerian writing developed in the same way as texting with emojis to write unambiguous sentences is now done, said Tenney. Central to this type of communication is the Rebus Principle, in which illustrated pictures are combined with individual letters to depict words and/or phrases. An example is combining the letter “D” and an image of a foot to convey the word “defeat.” The transformation of writing from logograms to complex narrative was one of the greatest human inventions and it happened because of the Rebus Principle, said Tenney.

“The Rebus Principle is used all the time in texting,” Tenney said. Over lunch, he challenged the students to parse the eight-buffalo sentence with emojis. The group activity gave students a firsthand experience of how ancient Sumerians conveyed meaning.

Tenney is a specialist in Assyriology and the civilizations of Mesopotamia. His research uses quantitative measures in conjunction with cuneiform sources to achieve a better understanding of the social and economic forces that affected ancient Near Eastern populations. He is the author of “Life on the Bottom of Babylonian Society: Servile Laborers at Nippur in the 14th and 13th Centuries B.C,” and the forthcoming "Ordering Society: Administrative Reality and Scribal Apparatus in the Middle Babylonian Period.” In 2010, he was awarded the Dissertation of the Year Award by The American Academic Research Institute in Iraq.