For a century, archaeologists have looked for the remnants of a wooden fort in Alaska – the Tlingit people’s last physical bulwark against Russian colonization forces in 1804. Now Cornell and National Park Service researchers have pinpointed and confirmed its location by using geophysical imaging techniques and ground-penetrating radar.

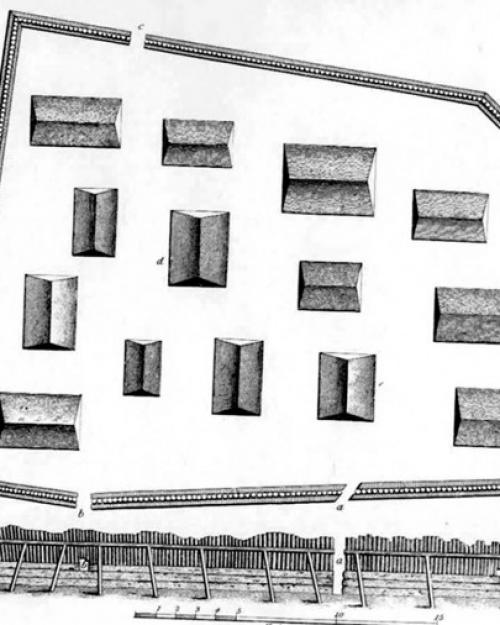

The Tlingit built what they called Shiskinoow – the “sapling fort” – on a peninsula in modern-day Sitka, Alaska, where the mouth of Kasda Heen (Indian River) meets Sitka Sound at the Sitka National Historical Park. The fort was the last physical barrier to fall before Russia’s six-decade occupation of Alaska, which ended when the United States purchased Alaska in 1867 for $7 million.

The research, “Geophysical Survey Locates an Elusive Tlingit Fort in Southeast Alaska,” was published Jan. 25 in the journal Antiquity, by authors Thomas Urban, research scientist in the College of Arts and Sciences; and Brinnen Carter of the National Park Service.

“The fort’s definitive physical location had eluded investigators for a century,” Urban said. “Previous archaeological digs had found some suggestive clues, but they never really found conclusive evidence that tied these clues together.

“We wanted to build a solid case,” Urban said. “Hence, we brought in geophysical imaging tools to gain perspective on the bigger picture and see how the clues of earlier investigations might fit together.”

In 1799, Russia sent a small army to take over Alaska in order to develop the fur trade, but the Tlingit successfully expelled them in 1802. The Tlingit figured the Russians would return, so over two years they built a wooden fort – the trapezoidal-shaped Shiskinoow. The Tlingit armed it with guns, cannons and gunpowder obtained from British and American traders.

By autumn 1804, the Russians and their Aleut vassals returned. The Tlingit held them off for five days, but this time the Tlingit suffered a setback when a gunpowder supply being carried to the fort from storage across Sitka Sound blew up in a canoe. The Tlingit clans escaped Shiskinoow by night across Shee (Baranov Island) to Cháatl Ḵáa Noow (Halibut Man Fort) and the Russians then established a trading post at what is now Sitka.

To find Shiskinoow, Urban created a grid to see if the electromagnetic induction methods could spot the potential outline of the fort, and then created a smaller grid for dragging the ground-penetrating radar. Urban’s modern tools picked up the fort's unusual perimeter shape.

Urban essentially covered all the potential spots for the fort.

“We were able to both confirm a location and rule out other potential locations,” Carter said. “There had been lingering doubts. But this is firm documentary evidence. When you bring remote sensing into it, you’re hammering together multiple lines of evidence on identifying where the fort was located.

“A large-scale survey was necessary to convincingly rule out alternative locations for this historically and culturally significant structure,” Carter said.

Said Urban: “We believe this survey has yielded the only convincing, multi-method evidence to date for the location of the sapling fort, which is a significant locus in New World colonial history and an important cultural symbol of Tlingit resistance to colonization.”

Funding for this work was supported by Sitka National Historical Park, the Alaska Regional Office (Cultural Resources Division), and the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, of the National Park Service.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.