Hungry giant predators, treacherous mud and a tired, probably cranky toddler – more than 10,000 years ago, that was the stuff of every parent’s nightmare.

Evidence of that type of frightening trek was recently uncovered, and at nearly a mile it is the longest known trackway of early-human footprints ever found.

The discovery, published in Quaternary Science Reviews, shows the archaeological findings of footprint tracks found at White Sands National Park in New Mexico. The tracks run for 1.5 kilometers (.93 miles) and show a single set of footprints that are joined, at points, by the footprints of a toddler. The paper’s authors have shown how the footprint tracks, as well as the distinctive shapes they left, show a woman (or possibly an adolescent male) carrying a toddler in their arms, shifting the toddler from left to right, and occasionally putting the child down.

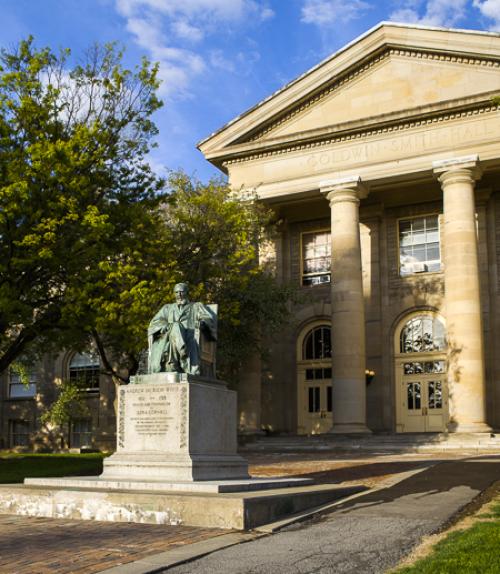

“When I first saw the intermittent toddler footprints, a familiar scene came to mind,” said Thomas Urban, research scientist in the College of Arts and Sciences and co-author of the study. Urban has pioneered the application of geophysical imaging to detect footprints.

“It reminded me of hiking or walking on the beach with my own small children,” Urban said. “You carry them for a while, then they may want to be put down or you may get tired and put them down while you rest for a moment.”

The tracks were found in a dried-up lakebed, which contains a range of other footprints dating from 11,550 to 13,000 years ago. The lakebed’s formerly muddy surface preserved footprints for thousands of years as it dried up.

Previously found in the terrain are the prints of animals such as mammoths, giant sloths, sabre-toothed cats and dire wolves. Sloths and mammoths were found to have intersected the human tracks after they were made, showing that this terrain hosted both humans and large animals at the same time, making the journey taken by this individual and child a dangerous one.

“This is likely to have been an incredibly hostile landscape, and we see that in the way that these tracks were made in a hurry,” said co-author Matthew Bennett, professor of environmental and geographical studies at Bournemouth University, in the U.K. “Footprints can tell us so much, and by the distance, direction and morphology of the prints, we can be quite accurate in understanding how these tracks were made, and what was happening at the time.”

The recently discovered footprints were noted for their straightness, as well as being repeated a few hours later on a return journey – only this time without a child in tow, which can also be seen from the tracks.

“This research is important in helping us understand our human ancestors, how they lived, their similarities, and differences,” said co-author Sally Reynolds, senior lecturer in hominin paleoecology at Bournemouth. “We can put ourselves in the shoes, or footprints, of this person (and) imagine what it was like to carry a child from arm to arm as we walk across tough terrain surrounded by potentially dangerous animals.”

Co-authors of the study included researchers from Cornell, Bournemouth, the National Park Service, Liverpool John Moores University and The Royal Veterinary College.

Read the story in the Cornell Chronicle.