Like many good mysteries, it began with innocent curiosity. Michael Fontaine was on paternity leave and, wanting “a small project” to occupy him between baby duties, thought he’d write about “Mater-Virgo,” a 17th-century play by Lutheran pastor Joannes Burmeister, based on a work by the Roman playwright Plautus.

But the last known copy of the play was looted from the Berlin Library during World War II. While searching for the play, Fontaine stumbled upon a mention of another, unknown Burmeister play, “Aulularia” (“The Pot of Gold”).

“It was like looking for India and finding America – you don’t know what you’re looking for when you find it,” says Fontaine, associate professor of classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. He detailed his discoveries in a new book, “‘Aulularia’ and Other Inversions of Plautus.”

Fontaine eventually tracked down the last existing copy of “Aulularia,” hidden away in the Copenhagen Library. None of the famous scholars of Burmeister’s day had ever read it, according to Fontaine.

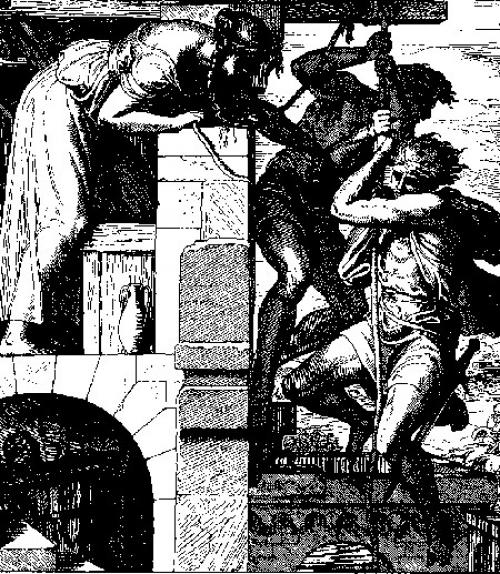

Plautus’ “Aulularia” is a pagan play about a paranoid Greek miser who finds a pot of gold and tries to hide it from his family; Burmeister transformed it into a story about Achan, a soldier from the Book of Joshua who steals gold from the sacred spoils of Jericho. Burmeister also incorporates the story of Rahab, the harlot of Jericho from earlier in the Book of Joshua who goes on to join the Israelite community.

The mysteries presented by the play didn’t end with its discovery. What was its underlying message? Once Fontaine determined that Burmeister wrote it in the year he spent in exile during the Thirty Years’ War, he realized the play was a commentary on soldiers’ abuses. Local records from a neighboring church helped Fontaine uncover that the play was written to commemorate and protest an attack on Burmeister’s own village church by Croatian soldiers, when several golden liturgical items were stolen.

“For me it was like a Sherlock Holmes detective story to figure this out; for Burmeister’s patrons it was probably obvious,” Fontaine says. “Life in Germany in 1627, when Burmeister was writing, was like Dungeons & Dragons but with guns – they were people still on the cusp of being knights in the medieval tradition but with firepower.”

Burmeister’s “inversion” of Plautus’ work was far more impressive than just rewriting the story. Burmeister kept every line in the same order and meter as in Plautus, preserved about 80 percent of the original Latin, and filled in the other 20 percent with new material – puns, riddles, anagrams, alliteration and “all manner of learned and ingenious wordplay,” Fontaine writes. “Every page turns up an incredible example.”

Since “Aulularia” was written for students of the classical high school in Hamburg, Fontaine had graduate students at Brown University act out his translation. “It performs as a play,” he explains. “People laughed at all the funny parts, and the students thought the characterizations were spot-on.”

Fontaine’s book includes “Aulularia” and its translation; a monograph-length introduction to the Latin text and the playwright’s life and historical times; and plot reconstructions and documentation of three lost plays.

“By studying the one complete play I found, I could see exactly the way Burmeister created his Christian inversions of these pagan plays,” Fontaine says. “Everything lines up perfectly. He’s brilliant.”

This article also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.