"The Sound of Mucus"

My wife had died a horrible and lingering death when my daughters were 14 and 10. Devastated the three of us sought solace, and to begin to recoup our lives we reinstated a group activity the three of us had enjoyed when they were considerably younger. We watched movies. Indeed, we would watch the same films over and over.

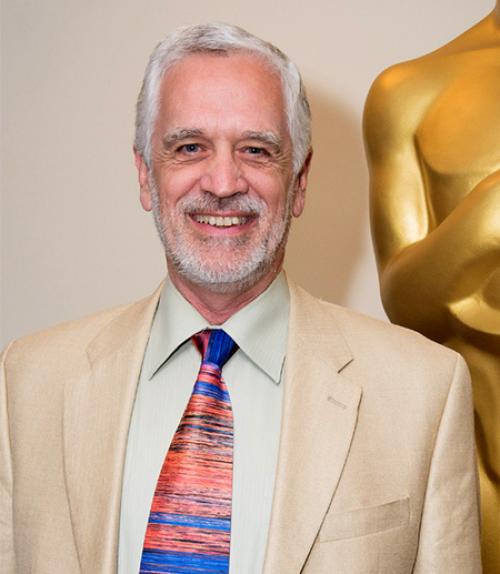

One of the films we saw anew was The Sound of Music (1965). As most Americans over 50, and many who are younger, will know it is an adaptation of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Broadway musical of the same name and starring Julie Andrews (as Maria) and Christopher Plummer (as Captain Von Trapp). For its genre it is still reasonable fare, and in an earlier era it was regarded as one of the most successful movies of all time. Some parts of it are serious (the rise of fascist Germany as manifest in Austria), some parts entertaining (more than a few memorable songs), and some parts romantic. To be sure, not everyone appreciates such mixtures, and to our current period eye it may appear mawkish. Memorably, Plummer referred to it as The Sound of Mucus. 1

What happens when one watches movies many times is the same as when reads the same book many times. If it is a good book or a good movie, one discovers new things. But even if it is only a moderately good movie this can be true. And one of the things I discovered in The Sound of Music was psychologically very interesting – a blindness to large things before our very eyes, a phenomenon two of our former graduate students in Psychology have parlayed into very successful careers. 2

The scene that changed my research life concerns a tipped rowboat, the Von Trapp children dressed in play clothes retailored from green bedroom curtains, and the confrontation between Maria and Captain Von Trapp. The children emerge from the water, drenched, and stand in formation. The Captain accosts them, dismisses them, and then accosts Maria.

Robert Wise, director of The Sound of Music, reported a conundrum that faced every filmmaker who filmed on location before extensive postproduction digital manipulations were possible – the change in weather. Clearly this scene was filmed on two consecutive days, indeed the last two days in Austria that the filming budget allowed. One cannot instantaneously dry wet clothes and reshoot the whole scene, and clearly retakes were needed (perhaps because Plummer broke up during the scene).

As one watches Maria and the Captain argue there is a large mountain in the background taking up perhaps a quarter of the screen. Across the shots the mountain is alternately shrouded in haze or appears in a pristine sky. The shift from one background to the other takes place at least nine times in the sequence, yet I didn’t notice it until perhaps the ninth time I viewed the film with my daughters. You can see it for yourself in the attached clip. 3 The phenomenon is quite striking and belies any confidence one might have in being attuned to our daily surrounds while engrossed in some narrative.

This was 1999 and it took me a decade to divest myself of other research interests and obligations, but I have been doing research on the structure and psychological impact of various aspects of movies for the last six years and am likely to continue for a good while more. Indeed I am hosting the international conference of the Society for the Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image this June at Cornell. All this because it seemed important for me to rewatch The Sound of Music countless times with my daughters.

1http://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2015/03/julie-andrews-christopher-plummer-the-sound-of-music

2 Daniel Simons (University of Illinois) and Daniel Levin (Vanderbilt University). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Change_blindness.

3 These days, of course, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) is full of lists of “continuity errors” of this kind. In addition, you will notice in the clip that the aspect ratio (width to height) of the image is 1:1 rather than 2.35:1. The reason for this is that my students and I have been working with movies and we systematically transform them this way so that they would have no commercial value.

About the Transformative Humanities Project

Faculty in the College of Arts & Sciences share a belief in, and speak often with our students, their parents, and the broader public about, the importance of the humanities for shaping deep and meaningful human lives. These short reflections by our faculty illustrate — in concrete and personal ways — how encounters with the stuff of the humanities have in fact been transformative in their own lives. In composing these reflections faculty were responding to the following assignment: Pick a single work in the humanities that has profoundly affected you — that inspires you, haunts you, changed the way you think about things, convinced you to pursue your life’s work, redirected your life’s work . . . in short, a work that has made your life in some way deeper or more meaningful.

This reflection is one of the many thought-provoking and inspiring faculty contributions to the “Transformative Humanities” project, part of the College of Arts & Sciences’ New Century for the Humanities celebrations. Read more of them on our New Century for the Humanities page.