“I have faith in the power of writing, of poetry, of literature, to do work in the world,” says Derrick R. Spires, Literatures in English. “The fact that the movie Black Panther exists, for example, and my little nephew calls himself Black Panther and is proud of his blackness: that’s what literature, that’s what the arts, do for us.”

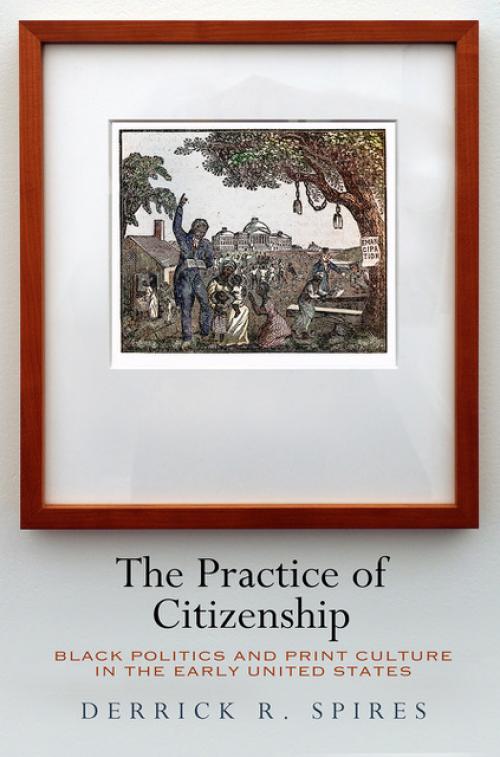

Spires has spent a lot of time thinking about the power of ideas and the influence of words to facilitate change. He focuses on early African American and American print cultures, citizenship, and African American intellectual history. His first book, The Practice of Citizenship: Black Politics and Culture in the Early United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019) has won multiple awards, including the Modern Language Association First Book Award.

“The premise of the book is to ask how our understanding of citizenship, particularly before the 14th Amendment in the United States, changes when we place Black writers as central theorists of citizenship rather than as people on whom the law acted,” Spires explains. “This also entails thinking about Black writing as more than simply a protest against white oppression or a reaction to racism.”

Black Americans Claim Their Citizenship

Many laws associated with systemic racism, says Spires, were in fact developed by white legislators and policymakers as a response to Black Americans who claimed their citizenship through their writings and through living lives steeped in actions that create community.

As an example, he points to the Pennsylvania State Constitutional Convention of 1837–38. The state had already emancipated its Black population years earlier and initially had no voting restrictions on Black men. (Women generally were restricted from voting throughout the United States at the time.) However, at the convention, delegates voted to insert the word "white" into the Pennsylvania constitution’s qualifications for the franchise. “This happens because Black folk had been voting, and their votes in key cities like Philadelphia and Pittsburgh could make a difference,” Spires says. “It was politically advantageous to disenfranchise them.”

“The question for today is, who are we continuing to ignore as they scream from the rooftops, 'This is wrong’?”

Even after voting was restricted, however, Black writers continued to call themselves citizens, Spires explains. “If we think of citizenship as something outside of what the law confers, or not reduced to single acts like voting, we begin to think of it as things we do to make community that the state facilitates but doesn’t necessarily create,” he says. “I think of it as neighborliness, the mutual-aid work that people do. Even today, in our current context, people like undocumented immigrants, who create community, can be seen as practicing citizenship.”

Starting in the 1830s, Black activists created national and state convention movements to make claims on behalf of Black citizens. The conventions organized around multiple issues, from the Black press and Black education to antislavery and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which facilitated efforts by slaveholders to kidnap people in free states who had been enslaved but had escaped north as well as Black Americans who had never been enslaved. “The convention movements especially supported Black newspapers,” Spires says. “They knew they needed them. At the National Color Convention of 1847, the delegates actually said, 'Our warfare lies in the field of thought,’ and to engage in that warfare, they knew they needed to control the means of print production.”

Social Movements: Parallels across Centuries

In today’s social movements are echoes of challenges that nineteenth-century Black activists faced, and their responses to those challenges, Spires points out. “The debate around the Fugitive Slave Law is really parallel to the debate today around sanctuary cities,” he says. “In the mid-nineteenth century, northern cities had created personal liberty laws. They gave Black people rights and access to courts to protect them from Southerners trying to enslave them; the federal Fugitive Slave Law did away with that. We see something similar in the Trump administration’s attempts to force state law enforcement to arrest and hold undocumented immigrants, even when they had committed no crime, so that federal agents could take them into custody and deport them.”

Another parallel between the social movements then and now centers on the effective use of media. “The convention movement arose out of Black activists noticing local problems and then creating institutions and infrastructure to address them, using the media of the day,” Spires says. “In the nineteenth century, that meant pamphlets, convention minutes, word of mouth, traveling lectures, and most importantly newspapers, the cutting-edge print media. We see the same thing today with movements such as Black Lives Matter, where a collective of Black women are using social media—Twitter, Facebook, Instagram—to organize a network of folks who are participating through a loose national organization and also founding local chapters to address very specific local problems.”

Nineteenth-Century Black Serial Literature

Spires is currently at work on his second book, tentatively titled Serial Blackness: Periodical Culture in Nineteenth-Century African American Literature. In it, he explores Black serial literature, which includes serialized novels, sketches by writers using pseudonyms, and poetry. “We are recognizing more and more that a lot of African American literature in the nineteenth century was happening in Black newspapers,” Spires says. “People were picking up the paper to read short stories and serialized novels, like the latest novel by [African American novelist] Frances Harper, in the same way that, today, we might tune in to HBO or Disney+ to see the latest episode of a show. And they were reading Charles Dickens, whose novels were serialized in Frederick Douglass’ Paper. They were fully participating in the broader literary culture of the time.”

Black writers who wrote slice-of-life sketches in the newspapers, using pseudonyms such as “Ethiop” and “Fanny Homewood,” particularly intrigue Spires. These writers would talk to each other through the newspapers, engaging in competitions and arguments, but at the same time also writing about going out on the town together. “I’ve been thinking of these writers as an early iteration of social media,” Spires says. “That also ties into the idea that Black activists use the latest media to do their work.”

Studying the past offers us important lessons, Spires says. “One of the things we learn in looking at the history of the United States is that things didn’t have to play out as they did,” he explains. “Black enslavement didn’t have to last as long as it did. Disenfranchisement didn’t have to last as long as it did. People debated both of these and said each time, 'No, we’re going to keep going as we are.’ And at each step there were people saying, 'This is wrong,’ but they were ignored. The question for today is, who are we continuing to ignore as they scream from the rooftops, 'This is wrong’?”