Elisha Cohn’s research generally focuses on Victorian literature, but she’s always been interested in animal studies, as well. There are dogs all over British fiction, she notes, often appearing as close companions to humans in works by Charles Dickens and George Eliot. Cohn, professor of literatures in English in the College of Arts and Sciences, has also written about Thomas Hardy’s representation of animals in his books and his personal commitment to animal protection.

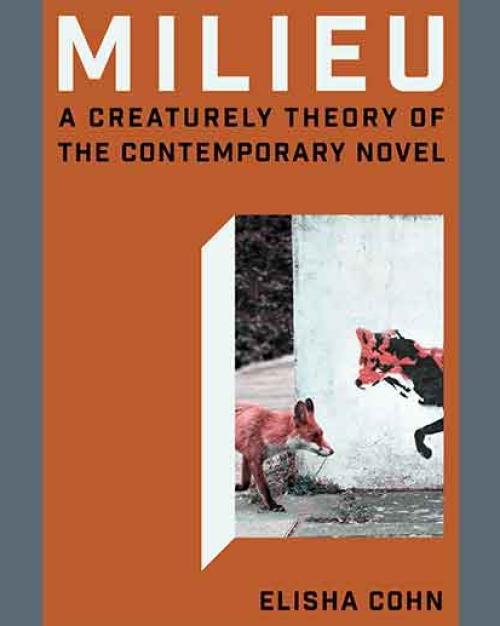

For her second book, “Milieu: A Creaturely Theory of the Contemporary Novel,” which came out this April from Stanford University Press, Cohn focuses on contemporary authors and the explosion of animals as characters in their works. She also explores the methods authors are using to give these characters a voice and how they are being portrayed as important parts of the environment of a story.

“The barrier to including animals in serious literary fiction is gone,” Cohn said. “I wanted to investigate how it vanished and what strategies novelists developed to surmount that barrier, to not take it in a merely sentimental direction.”

Another impetus for this current line of research came as Cohn was preparing for her class, Literature and Medicine, which included studying the writings of biologist Jacob von Uexküll and philosopher George Canguilhem and their ideas about how living beings perceive their environment.

Cohn surmises that the current prominence of animals in fiction could also relate to climate change and today’s environmental awareness. “Writers today have been aware of environmental catastrophes for their entire lives,” she said. “Today there’s a lot of emotional investment in certain species and our interactions with them.”

Earlier fiction is human centered, though can include stories of humans triumphing over animals, sympathizing with them, or sometimes both, Cohn said. But today’s novelists are constructing worlds in which animals and their senses are central, along with the worlds of their human counterparts, not sentimentalized or anthropomorphized.

“The impulse has been to resist our sentimentality to animals, to not look at the strengths of interspecies relationships,” she said. “But an underlying goal for me is that we want people to care about our environmental fate on the earth, to use those emotional bonds that we have and legitimate them. They can be complex and they can be ambivalent but they’re important too.”

The chapters of Cohn’s book deal with conceptual dynamics of milieu, some focusing on the use of specific animals and others on the storytelling methods authors are using in these works. The book explores fiction by Téa Obreht M.F.A ‘09, Yoko Tawada, NoViolet Bulawayo M.F.A. ’10, Sigrid Nunez, Jesmyn Ward, Linda Hogan, Lucy Ellmann, Amitav Ghosh, and Aminatta Forna.

“I was interested in thinking about narrative style as an environment, an environment for creating certain kinds of experiences and making possible certain kinds of thoughts for readers,” she said. “Not only are many of these novels thematically representing how people and animals interact in a physical environment, but the style itself is an environment that produces a set of feelings and thoughts about what’s being depicted.”

Novelists in this style can be more poetic, describing scenes in which animals are making their way through a setting, encouraging readers to slow down and take in the present moment, Cohn said. They also use metalepsis, shifting their narrative mode back and forth, much more than other authors.

Cohn said the book shows that animal studies and environmental studies are deeply related issues. “The very idea of environment has to do with how we perceive it. Novels are one way we shape our perception and can reshape our perception,” she said. “This book is as much about the contributions of literature and literary studies to environmental thought as it is to thinking about animals as such.”