One hundred and fifty years ago, the “radical” idea that was Cornell University became a reality.

At the inaugural ceremonies Oct. 7, 1868, university founder Ezra Cornell reinforced new educational concepts. “I hope that we have laid the foundation of an institution which shall combine practical with liberal education, which shall fit the youth of our country for the professions, the farms, the mines, the manufactories, for the investigations of science, and for mastering all the practical questions of life with success and honor,” Cornell said. “I trust we have laid the foundation of [a] university … where any person can find instruction in any study.”

As Morris Bishop, professor of Romance literature and a university historian, wrote in “A History of Cornell” (1962), Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, co-founder and the university’s first president, believed that in addition to a land-grant education in the mechanical and agricultural arts, higher education needed to be grounded in a traditional arts and sciences curriculum.

In October 1866 White presented an organizational plan to the university’s board of trustees. Bishop called the plan “a manifesto of a radical, enlightened scholar, rebelling against the obscurantism of the established colleges.”

Cornell historian Carl Becker, author of “Cornell University: Founders and the Founding” (1943), wrote that the university “had become, in short, famous or infamous … for its ‘radicalism’ – its frank and publicly announced departure from conventional and religious ideas.”

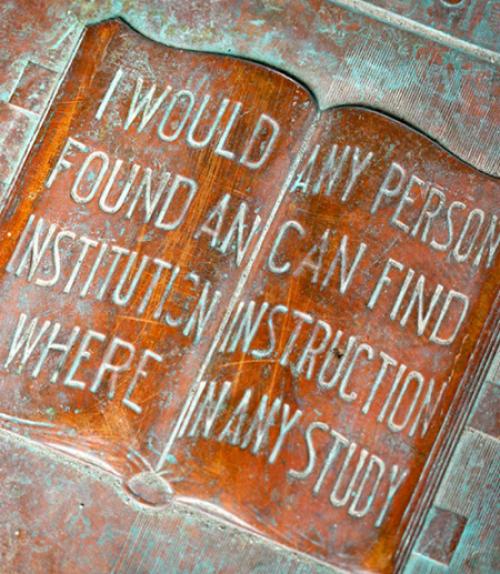

Both Cornell and White wished to incorporate these ideas into the official seal. In early 1868, months before the university opened, the men settled on a polished phrase: “I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study.”

Students would be allowed to take elective classes, a fresh idea in an era of fixed curricular requirements. Even more radical, the university was nonsectarian and it offered a work-study program to allow students to defray tuition costs. So popular were these concepts that 412 students matriculated at Cornell in 1868, the largest entering class ever admitted to a U.S. college at that time.

Arguably, neither Cornell nor White would be surprised at how well the founding principle of “… any person … any study” translates and still stands strong today:

Meisam Zaferani, a doctoral student in the field of food science from Iran, studies microfluidics – inherently multidisciplinary research. “It’s not just a motto; I think it is an essence,” he said. “In my research you need to know chemistry, biology, physics, mathematics, materials science and microfabrication. Ezra Cornell was a genius. One hundred and fifty years ago, he knew people would believe in interdisciplinary science. The whole idea of ‘… any person … any study’ is that there is no border in science.”

For Marisabel Cabrera ’21, the founding principle “is one of the most powerful strengths at Cornell,” she said. “I wanted the opportunity to study different things.” Cabrera has melded her passion for music and her newly discovered love for linguistics and natural language processing into a double major in music and language.

For Barron Williams ’19, the ethos is “an ideal that Cornell continues to aspire to,” he said. “I think that history has shown that Cornell has been very active in making sure it is diverse and open to a lot of students. Here, any student can pursue what they’re passionate about.”

Some students carry “… any person … any study” around the world when they graduate. Murodbek Laldjebaev, Ph.D. ’17, who studied natural resources, teaches at the University of Central Asia, with students from Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. He employs the philosophy in his classroom.

“While teaching human geography I can tap into my background to explain complex issues by drawing on economics, ecology, political science, sociology and other subjects,” Laldjebaev said. “Students find such interdisciplinary discussions rich and interesting. I also encourage students to think beyond their majors to help them better understand problems and seek solutions.”

Samir Salih ’19, who arrived in the United States from Sudan about 15 years ago, is familiar with the founding principle. “When I first heard that, I wanted to know the history behind it. Cornell was ahead of its time in terms of diversity,” he said. “This motto of Cornell University has allowed me to understand who I am, as I’m not a first-generation American.”

Said Brenna Garcia ’20: “I’m surrounded in my classes by people who are from so many different countries, places and perspectives. I’m not just surrounded by people who have the same opinion as me, or experience as me, or life story as me.”

As the university marks 150 years since opening its doors, Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Avery August will moderate a panel discussion, “Reflections on What ‘… Any Person … Any Study’ Means,” Monday, Oct. 29, from 4 to 5 p.m. in Call Auditorium of Kennedy Hall. It will feature Cornell faculty members describing how their research and professional experience reflect Ezra Cornell’s founding vision, and will be followed by an ice cream reception.

This story also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.